It was a homecoming like no other. On 4 May, hundreds of people gathered in Dubbo, in western New South Wales, for the unveiling of a statue of William Ferguson, one of Dubbo’s most famous sons. “We see monuments of Captain Cook and mayors,” says Rod Towney, who helped to campaign for this one. “But what about us?”

Many wore white t-shirts featuring a picture of the hero of the day and the words “William Ferguson. Fighter for Aboriginal Freedom.” The Travelling Wiradjuris, a country music band comprising the region’s Wiradjuri people, played from the rotunda in the town centre, where the statue stands. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal speakers alike — including state Nationals MP Dugald Saunders, Dubbo’s mayor Ben Shields, and journalist Jeff McMullen, an Aboriginal rights advocate — praised Ferguson. Jenny Munro, a Wiradjuri elder, told the crowd the day would be the “start of a new era that will see statues of black men and women in towns and cities all over Australia.”

How different from 1937. In June that year in Dubbo, William Ferguson launched the Aborigines’ Progressive Association, a body the likes of which Australia had never before seen. It called on Aboriginal people to take charge of their own affairs in a country that had deprived them of basic human rights.

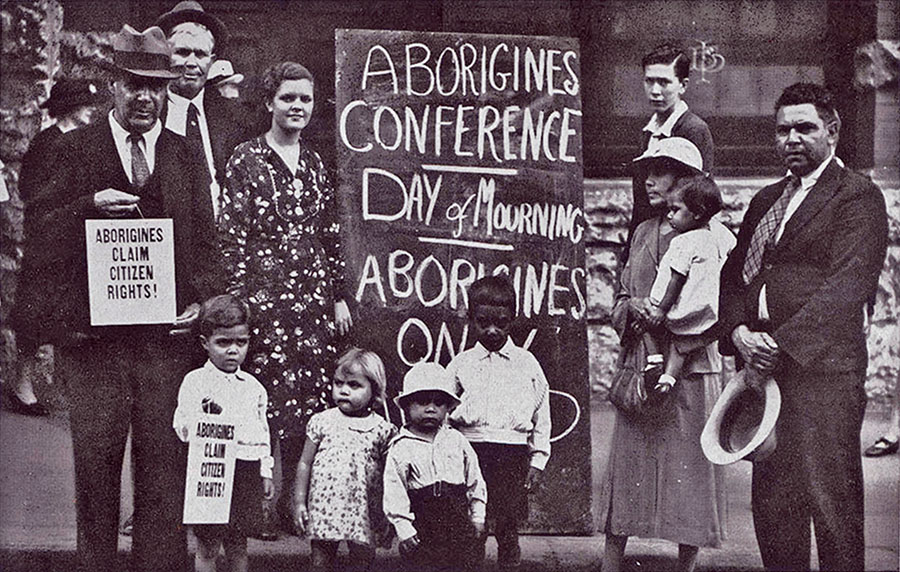

Six months later, on Australia Day 1938, Ferguson helped to organise a Day of Mourning and Protest in Sydney, while the city thronged with crowds celebrating 150 years of white settlement. About one hundred Aboriginal people convened defiantly at Australian Hall in Elizabeth Street, a few blocks from Sydney Town Hall, where processions of sesquicentennial floats marked the triumphs of British colonialism.

The Aborigines’ conference passed a resolution condemning the “callous treatment of our people by the whiteman during the past 150 years” and calling for “a new policy which will raise our people to full citizen status and equality in the community.” (After a battle by Jenny Munro and others to save it, Australian Hall was added to the National Heritage List in 2008.)

That event was also a first. Besides Ferguson, those gathered there included William Cooper from Victoria, Jack Patten from La Perouse in Sydney, and Pearl Gibbs, who later settled in Dubbo, where a large mural of her overlooks that city’s park. The Dubbo statue could help bring the leadership of this remarkable group of people back into Australia’s historical narrative.

Born in the Riverina district of New South Wales, William Ferguson started working in shearing sheds in 1896, aged fourteen, after just two years of formal education at a mission school. He became a unionist and joined the Labor Party. Outraged at the power of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board, a body that controlled Aboriginal people’s lives on reserves, he demanded its abolition.

At the Day of Mourning conference, Ferguson described conditions he had witnessed in his travels: “The dreaded disease of TB has made its appearance among our people, and is wiping them out, right here in New South Wales.” Two months earlier, at a public meeting Cooper had called in Melbourne, Ferguson said of life on reserves, “It would be better if they turned a machine gun on us.”

William Ferguson (left) and other participants in the Day of Mourning in Sydney on Australia Day 1938, as shown in Man magazine.

Ferguson and Cooper found two unlikely allies in the white world. William Miles, a businessman, owned the Publicist, a magazine edited by Percy Stephenson, a former Rhodes Scholar and one-time communist. Known as “Inky,” Stephenson by then had become anti-British, pro-fascist and a strong Australian nationalist. Aboriginal scholar Marcia Langton and writer Jack Horner have argued that Stephenson was “probably in sympathy with the Aborigines on nationalist grounds.”

Stephenson helped arrange publication in 1938 of the Abo Call, a monthly magazine billed as “The Voice of the Aborigines,” and gave Jack Patten, its editor, a desk at the Publicist. The Abo Call was one of only two known publications to report fully the proceedings of the Day of Mourning conference. In yet another unlikely twist, the second was Man, a popular risqué magazine that also published reputable fiction and current affairs articles and pictures. Under the heading “Aborigines Meet, Mourn While White-Man Nation Celebrates” the magazine ran two pages of pictures recording the event in Australian Hall, and quoting Ferguson: “We have been ‘protected’ for 150 years, and look what has become of us.”

The Sydney Morning Herald, by contrast, ran just a six-paragraph story of the Aborigines’ conference amid pages of stories and pictures extolling “Australia’s Day of Rejoicing” and “Milestones in Australia’s March to Nationhood.” An editorial in the Age observed a bit more sharply that the Aborigine had been cast as the skeleton at the feast on Australia Day 1938.

After the Sydney conference, Ferguson and his colleagues ramped up their campaign. In late January 1938 a deputation met prime minister Joseph Lyons, his wife Enid, and interior minister John McEwen. They presented a policy known as Ten Points, which demanded that Aborigines have the same education as white people and be allowed to own land. “Why give preference to immigrants when our people have no land and no right to own land?” Ferguson asked. It called for the Commonwealth to take control of all Aboriginal affairs. That reform had to wait another twenty-nine years until Australians approved a bigger role for the Commonwealth, by a record majority, in the 1967 referendum.

The setbacks seemed interminable. In 1949, when Ferguson was vice-president of the Australian Aborigines’ League, Ben Chifley’s Labor government dismissed calls for changes Ferguson had drafted to its Aboriginal policy. Ferguson quit the Labor Party in dismay and stood for federal parliament in the 1949 election as an independent in the seat that included Dubbo. His platform centred on the newly promulgated United Nations Declaration on Human Rights, which said that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” He was not elected. Ferguson collapsed after giving his final campaign speech in Dubbo, a few metres from where his statue now stands; he died not long after, aged sixty-seven.

Among William Ferguson’s family members who gathered in Dubbo for the unveiling, Alistair Ferguson had driven from Bourke, about 370 kilometres northwest. For the past six years, Alistair has successfully pioneered a project, known as “justice reinvestment,” to cut crime and imprisonment rates among Bourke’s young Aboriginal people.

Alistair cites his great-grandfather’s battles as his inspiration. “Human rights is a work in progress right across the globe,” he says. “Martin Luther King had a dream in America in the 1960s. My great-grandfather had a dream long before that. The Bourke project is showing how William Ferguson’s work is continuing. It’s not about me. I’m just the vehicle. It’s unfinished business.”

William Ferguson’s grandson, Willie Ferguson of Lightning Ridge in northwest New South Wales, cut a striking figure in Dubbo: tall, slender, with a grey beard and swept-back grey hair, dressed in a red country shirt and black trousers. He was born just five years before William died, but recalls his grandfather as a “strong man with a strong voice.”

Willie and Rod Towney, a Wiradjuri man, lobbied the Dubbo Regional Council to support their bid for a statue of William. The state government eventually provided about $120,000; Aboriginal figures and their supporters raised extra funds.

The sculptor is Brett Garling, who owns a gallery in Wongarbon, a hamlet on the Mitchell Highway near Dubbo. “I had no idea who William Ferguson was,” says Garling. “It’s not the sort of thing we were taught in schools. Yet when I learned his story, I thought that if he was American a movie would be made about him.” Garling worked from photos of William, and used his grandson Willie to capture “basic bone structure.” The result shows William Ferguson leaning slightly forward with a rolled-up newspaper in one hand: a typical stance when he spoke to crowds in the Domain in Sydney in the late 1930s.

Madeline McGrady, a pioneering Aboriginal filmmaker, and Cliff Foley, an Aboriginal land rights campaigner, were among many who travelled to Dubbo for the event. When William Ferguson took a stand for Aboriginal rights there in 1937, Dubbo was a small town on the edge of the western plains, where wool was king. It is now one of Australia’s biggest regional cities, with almost 40,000 people, about 15 per cent of them Aboriginal. With the federal election campaign in full swing, several reflected on how far Australia had come in the eighty-two years since Ferguson’s stand.

Land rights and native title have largely been won. But some people point to quite recent events to suggest that William Ferguson’s struggle is far from over. Just twelve years ago, John Howard as prime minister harked back to the era of white supremacy when he launched the Northern Territory Intervention, sending troops to take control of seventy-three remote Aboriginal communities and suspending the Racial Discrimination Act there. The exercise had all the hallmarks of the old Aborigines Protection Board that Ferguson had fought to abolish.

There is something of a stark choice on Aboriginal policy at this election, too. Labor promises to implement the call by Aboriginal people two years ago at Uluru for a First Nations Voice to parliament, calling it the party’s “first priority” for constitutional change. The Coalition government, under Malcolm Turnbull, dismissed the proposal. “If Bill Shorten says he’ll do it,” says Rod Towney, “he needs to listen and be true to his word.”

Mark Coulton, the National Party MP for Parkes, the federal electorate that includes Dubbo, had left town earlier that morning, before the statue’s unveiling. Fighting his fifth campaign to hold the biggest federal seat in New South Wales, Coulton drove to Warialda, his hometown, ahead of visits to the towns of Menindee and Wilcannia. A crippling drought and problems with the Murray–Darling river system seemed his priorities. Nonetheless, he praised the Ferguson legacy through the achievements of Alistair Ferguson’s project at Bourke: “It’s worked so well because of the strong local ownership and leadership.”

William Ferguson’s statue is bound to leave an even more enduring legacy, perhaps helping to head off another heavy-handed government policy like the Intervention. “A sculpture opens people’s minds and imaginations, and lets them learn why he’s there,” says Brett Garling, the sculptor. “He was a game changer.” •