When my friend’s parents recently arrived in Australia to visit their daughter, the customs officer registered that they were destined for Canberra. “Why the hell are you going there?” he asked, apparently by way of a welcome. If the language wasn’t exactly out of the Tourism Australia handbook, the candour was unexceptional. When Canberra is the topic, normal courtesies are suspended. As my friend added when she passed on the anecdote, it’s hard to think of another city whose residents are routinely subjected to an enumeration of its alleged flaws by complete strangers.

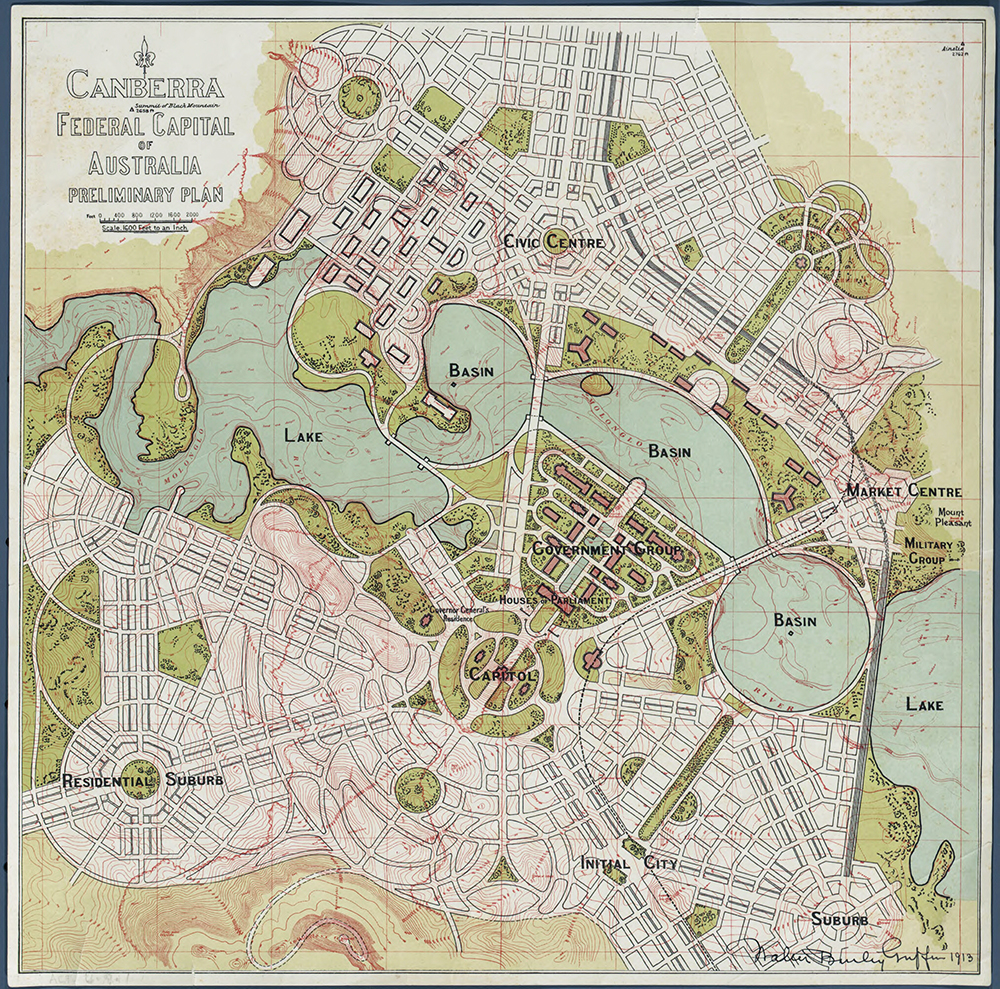

More often than not, the critics are also ready with a diagnosis, often starting with something about the wrongheadedness of planned cities. When journalist and former political staffer Martin McKenzie-Murray launched his polemic against Canberra in its centenary year, he located the origins of Canberra’s supposed shortcomings in Walter Burley Griffin’s 1912 design for Australia’s new capital. “What was splendid in the vision,” wrote McKenzie-Murray, “was sterile in the living. Griffin had designed a city that pre-empted the primacy of the car, which was both prophetic and pathetic.”

It may seem natural enough to hold the planner responsible for how the plan turned out — and, in conflating the Griffin Plan with Canberra today, McKenzie-Murray was only following common practice — but this is to misunderstand Canberra completely, including its ability to alienate. Canberra only embodies Griffin’s distinctive vision in a very partial sense, and it is the gap between plan and reality that explains the way the city looks, feels and functions today.

During his stint as director of federal capital design and construction between 1913 and 1920, Griffin laid out the triangle that defines the heart of Canberra (marked today by Parliament House at its apex, with Commonwealth and Kings Avenues extending across the lake to meet Constitution Avenue at the base). But rather than establishing a parliamentary triangle, these lines were intended to be the borders of Canberra’s central business district. It would certainly be a unique CBD, with the distinctive purpose of representing the will of a nation, but it would be no less intense and energetic, majestic and monumental, for that.

In Griffin’s original plan, a stadium was to be located on the shore of the lake at the end of today’s Anzac Parade. (This is the point where Griffin’s land and water axes intersect, which could be considered the centre of the city.) As Griffin specified in his 1913 report on the preliminary city design, the stadium would be “recessed into the slope of the bank, where it does not interrupt the continuous vista along the land axis.” It was to be flanked by a theatre and an opera house and then, extending along the foreshore, museums, galleries, public baths, a gymnasium, and even a zoo.

Walter Burley Griffin’s design for the Federal Capital of Australia, from his 1913 preliminary plan. National Library of Australia

Running along this cultural and recreational precinct, Constitution Avenue was to have formed Canberra’s main street. A grand boulevard, as important to Canberra as Swanston Street is to Melbourne, and just as busy and built up, it would have joined the two main nodes of Griffin’s municipal city: Civic at one end and the central train station and main shopping and commercial precinct (where Russell and the nation’s defence headquarters now stand) at the other.

Griffin designed a city that would respond to the natural landscape without resiling from the fact of being a city. As well as being the gateway to the capital, Canberra’s railway station was intended to be a grand edifice imbuing the city with a monumental unity. Griffin even countenanced the idea of buildings rising above the train station on what’s now called Mount Pleasant.

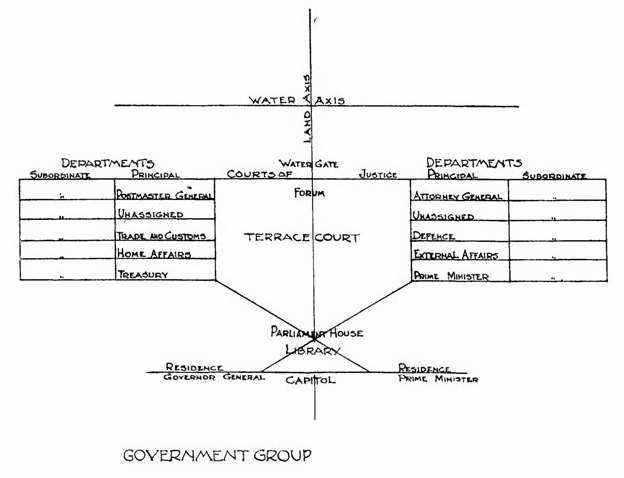

On the south side of the lake, Griffin’s “Government Group” was to have housed the entirety of the public service, forming a major centralised employment centre, buzzing with activity and connected with the rest of the city by streetcars running along Kings and Commonwealth Avenues. Additional bridges would have joined Acton Peninsula and Albert Hall, Kingston and Russell, and Black Mountain Peninsula and Weston Park.

Today, Griffin’s immense triangle marks the centre of Canberra, but it is largely empty of the things — buildings, businesses, night-life even — he imagined filling it. The incongruity largely explains the capital’s capacity to confound. When visitors to Canberra arrive only to ask, “Where is it?” what they are really experiencing is the absence of Griffin’s city, like the disconcerting twitch of a phantom limb.

When Canberra’s stadium was finally built in the 1970s, it was situated not on the shore of Lake Burley Griffin but at the Australian Institute of Sport in Bruce, a suburb of one of Canberra’s satellite towns. Canberra Station was never relocated from the nebulous region where Kingston blurs into Fyshwick; the main street that was to extend along the base of the triangle never materialised; the theatre ended up in Civic, the national museum on Acton Peninsula, and the zoo at Scrivener Dam; and the opera house remained a pipedream.

The buildings Griffin imagined populating the triangle were not replaced by other buildings so much as parks, car parks and a variety of nondescript spaces of indeterminate use. Where Griffin envisaged the city, as both national capital and municipal centre, filling out the triangle and encircling the lake, Civic hangs off one corner of the triangle and only by a thread. The triangle that was meant to be the centre of Canberra is instead a rarefied space, largely removed from the daily life of the city, suffused with a strangely deserted feeling.

Yet the Griffin Plan continues to get the blame. “Whisper this,” began a recent critique of “Car-berra” in the Canberra Times. “I wonder whether Walter Burley Griffin got it quite right. There, I’ve said it.” Canberra is indeed a city in which going to the football and then the pub, or the art gallery then a restaurant, or the train station then a hotel, often entails a car journey. But this is precisely because it lacks the dense concentration of activity in the city centre that Griffin provided for.

In Griffin’s city, the northern shore of the lake would have been “filled with crowds of people spilling onto its concourse to go about their daily business; to attend sporting events in the National Stadium; to visit the opera, theatre or museums; to go shopping,” according to James Weirick, professor of urban development and design at the University of New South Wales and an expert on the life and work of Walter and Marion Griffin. Instead, the atmosphere today is better evoked by Secret City, the political thriller based on the novels by Chris Uhlmann and Steve Lewis, in which the lake’s foreshore consistently features as an uninhabited location for clandestine meetings between spooks, hacks and pollies.

In Griffin’s design, the activities of the federal government were to form an integral part of Canberra’s CBD. His 1913 report contains a diagram in which all the major departments are aligned along Federation Mall, with subordinate departments behind them. Griffin’s mall was to acquire definition from the government buildings lining it, but only two of them were ever built, and Federation Mall dissolves into more open space: parks, gardens, traffic islands, ground-level car parks (ten, no less, in the parliamentary zone) and areas, not quite parks but definitely not ovals, that host occasional games of lunchtime touch football.

Walter Burley Griffin’s layout of government buildings, from his 1913 preliminary plan.

As rich and vital as the national cultural institutions are, their location in this otherwise empty landscape only compounds the dispiriting feeling that what was intended to be the nerve centre of the nation has turned out to be more like a theme park for Year 6 civics excursions.

Griffin saw the Molonglo Valley as forming an irregular amphitheatre, with the peaks of Black Mountain, Mount Ainslie and Mount Pleasant representing the upper balconies, and the dress circle sloping down the northern banks of the Molonglo. Griffin’s stadium was the front row, looking across to the other side of the lake where Parliament House was to be situated on the natural rostrum of Camp Hill, and the great drama of national life would play out.

“What you would have along the base of the triangle would be the everyday life of the city and the cultural life of the city and the freedom of public space,” Weirick tells me, “and then the convergence of the avenues would express in physical form the will of the people… And the government is across on the south side of the lake because the people put them there under our system of representative democracy.” The government buildings were to be set out “like a diagram of the Australian Constitution,” he goes on. “Everybody who worked or visited Canberra, as they moved around the city, would understand its fundamental functions, the rights and responsibilities, and the institutions created under our Constitution. The city would be self-evident.”

Today, there is neither stadium nor drama nor diagram, and Parliament House stands alone, surrounded by the moat-like State Circle. Attending a protest there feels like entering the civic version of a padded cell. Corralled into a special spot hundreds of metres away from a building that is itself removed from the rest of the city and insulated by the empty expanse of the parliamentary zone, inside a capital distant from the affections of the nation, it is as though expert choreography is ensuring that the rituals of democratic participation can play out without causing any disturbance. As Kim Dovey, professor of architecture and urban design at the University of Melbourne, has argued, politics has been abstracted from the polis.

Griffin’s plan was buffeted in the first instance by two world wars and a depression. When, at long last, prime minister Robert Menzies threw his weight behind the city’s development, it finally became feasible to realise Griffin’s vision in full; the lake was created and the public service fully relocated to the capital.

At precisely this moment, though, the newly formed National Capital Development Commission, or NCDC, created a new plan that would overlay Griffin’s. The Y Plan stipulated that Canberra would be made up of town centres, separated by large swathes of bushland and joined by freeways. So at the very moment when it became possible to complete the centre of Griffin’s Canberra, the NCDC determined that the city would have multiple centres; and just when the departments of the federal government finally moved to Canberra, it decided to locate them almost anywhere but in the triangle that Griffin had made to house them. The architects of the Y Plan believed they were faithfully applying Griffin’s principles on a larger scale, but in practice it meant that Griffin’s plan for the centre of Canberra would never be realised.

In 2004, the NCDC’s successor, the National Capital Authority, published The Griffin Legacy, in which its authors captured Canberra’s predicament perfectly. “The Griffin Plan sought a seamless connection between the functions and setting of the ‘federal city’ and the everyday life of the ‘municipal city,’” they wrote. But, today, “physical barriers and empty undeveloped spaces separate federal and local activities, tourists and residents, and ‘town and gown.’” A critical element of any potential solution, the authors argued, was to extend Civic down to Lake Burley Griffin; “build Griffin’s West Basin promenade to serve as a waterfront focus”; and “activate the foreshore area with a broad mix of retail, residential and tourist accommodation, including restaurant, cultural and entertainment uses.”

The eight- and twelve-storey apartment complexes now under construction around City Hill are the first signs that The Griffin Legacy’s proposal to extend the city to the lake is finally being realised. Development is slated to continue over the series of asphalt car parks and clover-leaf turning circles that consume prime land between City Hill and Parkes Way; and land-bridging over Parkes Way will provide vehicle and pedestrian access into West Basin, the strip of foreshore running between Commonwealth Avenue Bridge and the National Museum.

At West Basin itself, plans are in place to reclaim almost three hectares of the lake to create a waterfront development with 2000 residential apartments, a public promenade, and lakeside dining and cafes, as well as community facilities and parks. This nascent development will, in effect, expand the New Acton precinct (centred around the unconventional Nishi building which has already done much to challenge preconceptions about Canberra) across Parkes Way to the water in one direction, and across London Circuit and Commonwealth Avenue to merge with the rest of the city in the other.

New Acton’s Nishi building under construction in 2013. Nick-D/Wikimedia

Griffin’s vision — in which the city and the triangle are one — may be lost, but the development of West Basin is potentially transformative. If the consequence of the half-implementation of the Griffin Plan is that Civic, the lake and the national capital area largely function in isolation from each other, this is the point at which all the city’s major elements can be reunited, to form the centre Canberra has never had. Where, at present, Canberrans have to make a special effort to visit the lake, often by car, the development of West Basin could recast it as the natural backdrop of daily life, as local residents enjoy their neighbourhood, workers spill out of offices into pubs, bars and restaurants, and tourists and revellers are drawn to the waterfront.

While what happens at West Basin won’t alter the triangle itself, it could at least create an interface between the national capital area and the daily life of the municipal city. In particular, it means that Commonwealth Park — one of Canberra’s most beautiful spots — could become much more accessible and well-used.

The potential for West Basin to become the clear central point Canberra currently lacks is heightened by the prospect of two other (albeit complicated and expensive) schemes. The proposal to relocate Canberra Stadium to the site of the ageing and ailing Civic Pool (not so far from the spot Griffin specified a century ago) would do much to create demand for restaurants, bars and hotels, and generate the concentration of activity that cities exist for. And when stage two of Canberra’s light rail eventually runs down Commonwealth Avenue past West Basin, and then on to Parliament House and Woden, the parliamentary zone will become more integrated into the life of the city.

The attempt to pin Canberra’s faults on the Griffin Plan is really part of a larger mistake. The bashers want to dismiss Canberra as flawed in its very conception. It was hubris to think Canberra could avoid the pitfalls of urban life, they gloat; instead, it has only created its own unique defects. But this is wrong. Infidelity to the Griffin Plan doesn’t discredit the plan itself, and nor does it diminish the virtues to which Canberra aspires more generally. The vision of a bush capital — a city that converses with its natural setting rather than seeks to conquer it, that does not relegate the environment to the periphery but incorporates it into its core, that refrains from towering over its citizens and instead speaks to them as equals, that privileges public space in a manner commensurate with its commitment to public service — is as urgent and compelling as ever. Canberra is not an experiment that has failed, just one that requires some thoughtful recalibration.

But some Canberrans don’t think any recalibration is called for. They like Canberra just the way it is, and see in the proposed development of West Basin an attack on the public space, bush setting and human scale that give Canberra its distinctive character. At a public seminar in March entitled “Developing Away Our Bush Capital?” the proposed development was described as an “apartment estate of high-rise buildings — permanently blocking or privatising public vistas of and across the lake” and leading to the destruction “of lakeshore public parklands including over one hundred trees” and “the picturesque, naturalistic lake edge.”

The critic was Richard Morrison, a member of the Lake Burley Griffin Guardians, a community group committed to “safeguarding the open space of Lake Burley Griffin and its lakeshore landscape setting.” Morrison, who has an extensive background in heritage conservation, also pointed out that the development plans are continuing apace while a 2010 nomination for West Basin’s Commonwealth Heritage Listing is still yet to be assessed. For the Guardians, the proposal to develop West Basin is not much more than a real estate development that will turn public parkland into luxury penthouses.

They are not alone in their concern that Canberra is losing its distinctive identity as dilapidated public housing blocks are demolished, vacant lots are sold off, land is rezoned, building height limits are increased, and high-rise buildings shoot up throughout Canberra’s city centre, town centres and along Northbourne Avenue, the main boulevard down which the newly minted tram now runs. Many Canberrans are expressing alarm at what one op-ed called chief minister Andrew Barr’s “fast track from Bush Capital to concrete jungle.” The former speaker of the Territory’s Legislative Assembly, Greg Cornwell, expressed a sentiment shared by many when he lamented that “sections of the business community and the ACT government itself seem determined to develop Canberra into another Sydney or Melbourne in the name of progress.”

When I meet Mike Lawson, a long-time Canberra resident and Guardians member, at West Basin, he places the plan to build the city to the lake in this context. “The ACT government needs $600 million a year in land sales to float,” he says. “So selling off ACT land is one of the prime industries in the ACT… Selling for economic value to the ACT government; increasing the value of that land; creating jobs for people in the construction industry; creating profits for developers; and creating an urban centre which then becomes an increasing tax base.” Why do three hectares of Lake Burley Griffin need to be reclaimed, Lawson asks. “Because it creates more land for development.”

James Weirick agrees about West Basin. “In my view it should stay as a public park, and they shouldn’t fill in the lake, and they should keep it as part of the open space system of Canberra,” he says. For Weirick, the critical issue is Parkes Way. As the authors of The Griffin Legacy identified, the six-lane freeway along which Canberrans speed between the city’s widely dispersed town centres is an obstacle that inhibits movement between the city and the lake.

A 2013 report for the ACT government by the Sydney architects Hill Thalis proposed that Parkes Way be turned into a split-level boulevard. Its gradient would be lowered, retaining its function as a major traffic artery, while a grid of local city streets would run over it at surface level, providing easy pedestrian and vehicle access to the lake. But Weirick believes such a proposal is far beyond the means of the ACT government. “The fact of the matter is that it’s an extremely expensive proposition to take the city to the lake, and the scheme has been stymied because everybody who has looked into it has realised the cost involved.”

Artist’s impression of Hill Thalis’s 2013 City to Lake plan for the ACT government. Hill Thalis

When the expense piles up, he says, the ACT government will inevitably give in to pressure from developers for more floor space in West Basin. “As has happened at Barangaroo [in Sydney], the developer keeps saying ‘give us more’ and Barangaroo has essentially doubled in floor space from where it started,” Weirick says. “And that’s what’s on the cards for City to the Lake.” The result will be “high-rise towers of a scale and footprint of the Nishi building and so on, and you’ll get awkward, misshapen, assertive buildings dominating the symbolic centre of Canberra.”

The person ultimately responsible for the development of West Basin is the head of the ACT’s City Renewal Authority, Malcolm Snow. Unsurprisingly, he offers a very different picture of what’s in store for West Basin. Snow has considerable experience in regenerating urban waterfronts, including at Brisbane’s Southbank. “Good waterfronts around the world exhibit some common qualities, and top of the list of those common success factors is really a priority around public space,” he says.

When Canberrans think lakeside development, their first point of reference is likely to be Kingston Foreshore. While Snow believes some Canberrans judge the development at Kingston harshly, he concedes that “certainly, mistakes were made and we’re going to learn from those mistakes.” Namely? “I think principally that they built the buildings first and then came back and did the public spaces later,” he says. He points out that, by contrast, the development of West Basin has begun with a new public park next to Commonwealth Avenue Bridge.

Snow is not prepared to quote exact percentages of residential and retail space but says, “What’s going to be absolutely critical is that this place works not only during the week; it works at night and it certainly works on weekends. Now if it’s to be that people magnet… it’s the diversity of use that’s critical.” The buildings, Snow insists, will not be “high-rise as those who perhaps regard themselves as detractors of the scheme would say.” They will be a maximum of six storeys along Commonwealth Avenue and Parkes Way and slope down to one or two storeys closer to the water, he says. The National Capital Plan also requires that buildings are set back at least fifty-five metres from the shore.

Snow calls attention to the fact that much of West Basin is currently consumed by car parks. This isn’t the only place where Canberra displays this puzzling indifference to the lake — something between outright rejection and a failure to notice it is there — and nor is it the only point where the capital offers incredible views for parked vehicles. At Russell, a sea of car parks is situated so as to distance the defence precinct from the water’s edge; at the Canberra Institute of Technology, the car parks are not even paved; Questacon, too, is set back from the lake, while the prime space by the foreshore is devoted to a car park; in Yarralumla, the shops are in the centre of the suburb while there is a large block of empty land next to Yarralumla Bay; the Australian National University expires around the Crawford School, maintaining a respectful distance from the water, and the spot where Sullivan’s Creek enters Lake Burley Griffin is virtually inaccessible. In this context, the West Basin development seems less like an assault on public space or natural bushland than an effort to address the wasteful underuse of space in the heart of Canberra.

It is true that there is also some pleasant park area at West Basin and a beach, of sorts. But, as Snow points out, “For those who want a non-urban lake experience there will still be approximately forty kilometres of undeveloped lake frontage.” The Guardians dispute that figure, but, suffice to say, Canberra has an abundance of naturalesque foreshore; it has parks; and it has open space. The development of West Basin will not change that. “Once complete,” says Snow, “the redeveloped waterfront will have approximately four hectares of new public space, including parkland.” It’s not parks or bush that Canberra lacks but their integration into the life of the city.

Near West Basin, Commonwealth Park is substantially cut off from pedestrian access by Parkes Way and Commonwealth Avenue. Similarly, Black Mountain Peninsula, a true highlight of the city and a place to which Canberrans should naturally gravitate, is dreadfully underused. The projected 5000 people that the redeveloped West Basin will bring to the lake’s shores each day, as well as improved pedestrian access to Commonwealth Park, should mean that more Canberrans will spend more time enjoying the city’s most beautiful public spaces. It is just possible that one day the lake’s shores will become the city’s playground in the manner Griffin envisaged.

Snow also takes issue with the Guardians’ claim that the West Basin development will block views to the Brindabellas. “This notion that the entire journey from City Hill to the lakefront is going to be obstructed is simply not correct,” he says, pointing to Henry Rolland Park, between Albert Street and the lake, which will remain undeveloped. Here, the Guardians do have a point: six-storey buildings will block the views across the lake as Canberrans drive along Commonwealth Avenue.

But Canberrans don’t suffer a shortage of nice views while they’re driving; the problem is that they are very likely to be driving when they experience nice views. Just as the lake is a place to drive to, the triangle is a place that, more often than not, Canberrans drive through. Canberra needs more opportunities to enjoy views of the lake and the Brindabellas from cafes, restaurants and pubs right by its shore.

As for Commonwealth Avenue itself, Snow is blunt. “I find Commonwealth Avenue, quite frankly, at the moment a really boring street, dominated by cars. It may as well be an arterial road. No street life whatsoever.” If you doubt Snow’s assessment, try walking from Civic to Parliament House. “Compare that, for example, to Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC,” Snow says. “Fantastic street.”

Will the character of the West Basin development ultimately be dictated by the demands of developers, as the ACT government seeks to recoup the cost of dealing with Parkes Way? “It is challenging from a technical standpoint,” Snow acknowledges. Something like the split-level boulevard proposal “would be hugely expensive. I mean many hundreds of millions of dollars.” But Snow argues that there are alternatives. He suggests decking or land bridges “that effectively straddle Commonwealth Avenue” as “a less costly but I would think, as an urban designer, an equally effective solution, in terms of improving connectivity.”

“What we are saying and will be saying to government is that this is a once-in-a-hundred-year opportunity to get this right,” Snow continues. “Parkes Way is a critical part of the transport infrastructure and the arterial road network of the city. It also, however, functions as a significant physical and psychological barrier. Overcoming that barrier in order to not just unlock development potential but also achieve a broader strategic urban objective, which is to link our CBD, the city centre to the best natural feature we’ve got in this city, called the lake, will itself generate other broader macroeconomic benefits for the city in the long term.” And very significant non-economic benefits, it can be added.

Whether the ACT government can be persuaded to adopt an enlightened long-term view of the project’s potential remains to be seen. As the City Renewal Authority negotiates a land swap with the Commonwealth and refines the West Basin master plan, it is good that the Lake Burley Griffin Guardians and others are keeping vigilant watch. There are obvious grounds for concern when politicians and property developers are involved, the pressures on the ACT budget are very real, and there are those who really do want to turn Canberra into just another city. The influential property developer Geocon, for instance, is perfectly open in its hostility to the ideals of the bush capital, and sometimes chief minister Andrew Barr gives the impression that he’s in its corner. (His proposed removal of Canberra’s ban on billboards is one worrying example.)

But it is wrong to defend Canberra’s distinctive character to the point of advocating the preservation of a foreshore dominated by car parks. It is a mistake to see the “best of town and country” where the actual existing layout of Canberra separates its citizens from the natural beauty of their city. And it is defeatist to hold that the difficulties involved in dealing with Parkes Way mean that this unfortunate barrier between the city and the lake should forever remain unaddressed.

The ideal of a bush capital proposes the arresting coexistence of what we had previously thought were incompatible opposites, a tension between open space and built form, natural environment and urban density, provincial stillness and cosmopolitan intensity. And it is precisely this tension that Canberra lacks as a result of the half-implementation of the Griffin Plan. Griffin replaced the traditional city centre of high-rise buildings with a lake and public parks, thus inverting the normal allocation of this space to the most powerful of private interests. In reconfiguring the traditional city, he was inviting us to relate to nature and each other in a new way.

As a capital, Canberra patriotically asserts its uniquely Australian setting while evoking a touch of antipodean irony about the very notion of being a centre. Today, though, Australians are more likely to take Canberra’s self-effacing nature as a sign of aloofness than of humility. Instead of a paradox, many just see a category mistake; rather than beholding a city unlike any other, many question whether Canberra is really a city at all.

The tantalising possibility in the extension of the city to the lake is that the tension between opposites at the heart of the bush capital ideal will be recovered, the paradox restored. Walter Burley Griffin’s fate was to be twice wronged: first, his vision for Australia’s capital was betrayed; then forever after he has been impugned for the flaws of a city he didn’t design. But idealists, by their nature, play a long game. It may be that the spirit of Griffin’s plan, if not the letter, is finally about to be realised. •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency Limited’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.