Does the home affairs minister have a problem in Dickson? Will he survive beyond the next federal election?

Following his easy victory five months ago, these might seem surprising questions. After a high-profile battle with Labor’s Ali French, and with the opposition and GetUp! throwing all their kitchen sinks at him, Dutton secured a 3 per cent swing to retain the seat with a healthy 4.6 per cent margin.

The Sydney Morning Herald and Age’s Peter Hartcher certainly believes it was a triumph for the incumbent, devoting a chunk of a recent article to agreeing that GetUp! was Dutton’s secret weapon in May.

Now, I’m quite a GetUp! sceptic. A report in March that a “series of powerful political campaigns” featuring GetUp! and unions would be targeting far-right Fraser Anning in the upcoming election sent a shiver down my spine. Exposure like that was exactly what the little-known senator craved. (In the end, despite their assistance, he got only 1.3 per cent of the vote and didn’t come close to getting a seat.)

In fact, I’m generally doubtful of claims made on behalf of on-the-ground campaigns, particularly by the parties. Somehow it always turns out that the winner ran a sublime campaign and the loser couldn’t organise a proverbial in a brewery.

But, for whatever reason, Dickson actually did underperform for the Coalition at this year’s election. The seat swung to the Coalition by less than the statewide figure of 4.3 per cent, and by less than all but one of the electorates it shares borders with. Blair swung to the Coalition by 6.9 per cent, Lilley by 5.0, Longman by 4.1 and Petrie by 6.8. The fifth, Brisbane, moved to Labor by 1.1 per cent. And that was the second relatively poor result in a row for Dutton, after a big fat 5.1 per cent shift to Labor in 2016 (compared with a Queensland swing of 2.9 per cent the same way).

And, remember, GetUp! was involved in the 2016 Dickson campaign as well.

The upshot is that Dutton’s two-party-preferred vote is now 54.6 per cent, against his party’s whopping state share of 58.4 per cent. On paper he’s safe as long as the Queensland vote remains sky-high, but a uniform swing in the state of 4.3 per cent, which would still leave the Coalition on a healthy statewide vote of 54.1, would see the minister out on his ear.

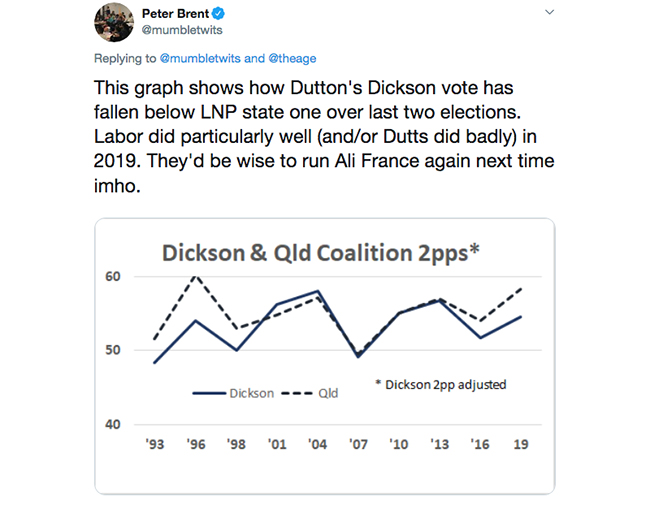

Those relative seat and state votes are illustrated by the tweeted graph below, which compares the Coalition two-party-preferred votes in Dickson and Queensland since the electorate was created in 1993. The former Queensland copper won it from Labor’s Cheryl Kernot in 2001, after which the lines converged; that improvement in the solid line relative to the dotted one is what we’d expect as a new member becomes known in the electorate and generates a personal vote. But the lines diverged again after 2013.

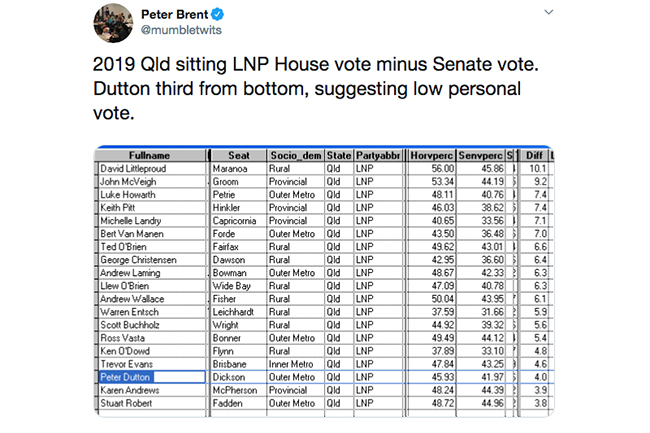

Another way to get a handle on how an MP is travelling in his or her electorate is to subtract a party’s Senate vote from the House vote in that electorate to give an approximate measure of an MP’s relative personal vote. A very popular local MP — someone a significant number vote for despite not supporting the party — would register a big gap. This table shows that calculation for all sitting Queensland LNP members in 2019. Dutton sits third from the bottom.

This measure has the drawback of depending partly on which minor parties and independents are running. But it adds to the evidence suggesting Dutton did poorly in May.

There are several possible explanations for these two recent below-par performances. One is that Dutton has simply become unpopular in Dickson; perhaps his energetic narrowcasting to the Coalition base is a turn-off for the broader constituency. Another is that (leaving aside redistributions, which are accounted for in the graph) the demographics of the electorate have changed and it is no longer as reliably Coalition-leaning as it was. That would explain the graph movement, but not the personal votes table. Either hypothesis, if valid, would not bode well for his future chances of success.

The cheerier scenario for him is that, despite his and Hartcher’s chortling, there were special circumstances in 2016 and 2019, namely that Labor (and, yes, maybe GetUp!) ran good campaigns and/or the Coalition ran bad ones. In 2016 the candidate was former high-profile state minister Linda Lavarch; she would have brought a personal vote. Lavarch ran for preselection this time but missed out to Ali France, who made a big media splash and was assisted by oafish comments from the sitting member.

This matters, because if these explanations were one-offs they won’t necessarily apply at future outings. By 2022 Dutton might have become more skilful at differentiating rabid Sky News consumers from semi-engaged voters. But Labor would be wise to run France again in 2022, if she’ll do it. If not her, then Lavarch.

But wait, help is also on the way for Peter from an unexpected quarter. In June I wrote about Labor’s bold but disastrous strategy of taking the fight up to the government on “border protection,” with the swashbuckling shadow home affairs minister Kristina Keneally determined to drag the issue back onto the front pages. Under Bill Shorten and his lethargic immigration shadow minister it was pretty much a non-issue, and whenever Dutton and the government attempted to whip up emotion it looked gratuitous, obvious — and nasty.

Only this week Keneally has tweeted that “airplane people” are “taking jobs away from Australians.” You see what she did there — two can play this game, Peter!

Ultimately this will assist the government. After all, when push comes to shove, who are you going to trust to keep those awful foreigners out?

And with his opposite number adopting his inflammatory language, it humanises Dutton. Perhaps he’s not so horrible after all. So add Keneally’s appointment to the positive side of the ledger for his re-election chances. •