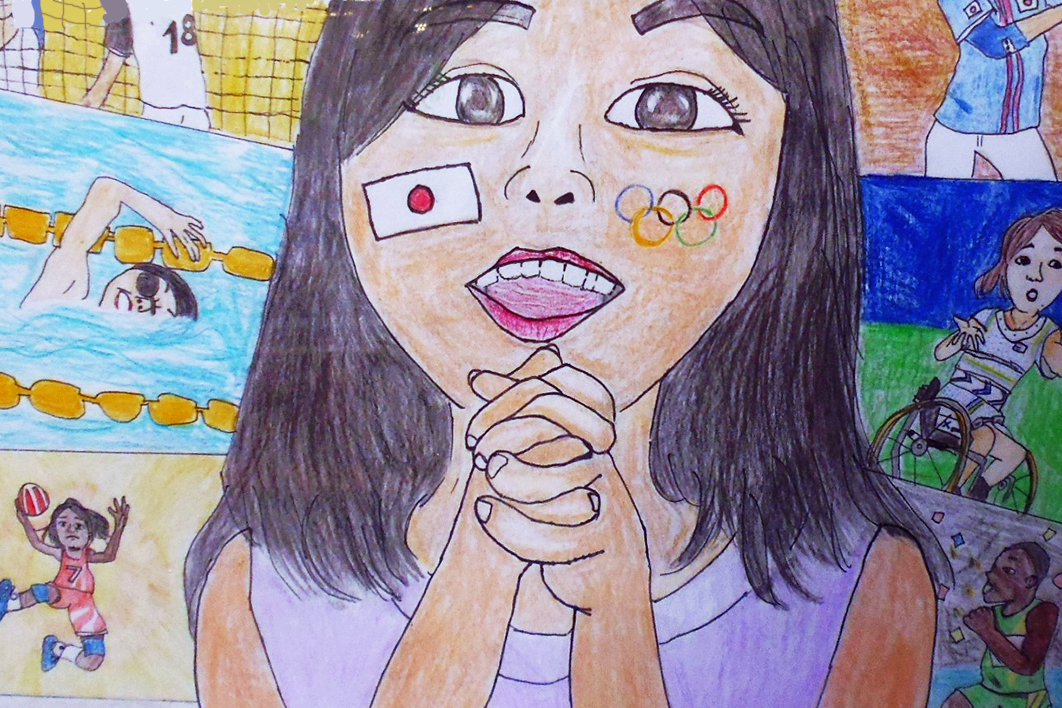

A gang of five poppets beams through a circle chain. They are so vividly drawn as almost to eclipse their national emblems. The Chinese girl’s smile is beatific, the Korean’s as radiant as her costume, while the American’s wink matches her cute blonde bob. A smart, green-shirted Japanese boy and a blue-eyed Brit in a Sherlock Holmes cap make up the set. Next along, clasped hands bridge the ocean to a harlequinade of flags. A team of manga pixies with floppy hair smashes it at table tennis. From more circles, a crew of bold girls swim, shoot, serve, lift weights, fire arrows. A dreamy angel with painted cheeks prays for victory. Superheroes fly to podium heaven in the glow of a bright red sun.

Cheery patriotism, benign internationalism, girl talent, radiant humour, sheer pizzazz: it’s all here. Lines from a world away ping in my ear: “The vale of tears is powerless before you… / Monsters of the year / go blank, are scattered back.”

That was back in January 2019, at a small railway station north of Tokyo. Local primary school students’ classroom posters for the city’s 2020 Olympics, fifty in all, had — for a few days only, it turned out — taken the place of advertising boards. Pure chance had put me there, and no doubt the discovery’s random and fleeting nature was part of the delight. Now, thirteen months on, as the Olympics inch towards the finishing line — warily eyeing the coronavirus’s spurt in the outside lane — that Miyahara hour feels as distant as the moon.

In part, that’s because a year ago the Olympics (here, the term embraces the Paralympics) were still more background hum than daily buzz. The transition to a new imperial era and the detention of Nissan-Renault executive Carlos Ghosn led the news, while the big sporting fixture on the horizon was rugby’s world cup. Even broadcaster NHK’s latest year-long Sunday night historical drama, Idaten, lacked sparkle. With the ageless Takeshi Kitano as a comic-monologue rakugoka, the series told Japan’s Olympics story from 1908 to Tokyo’s hosting in 1964. Artistic flaws, premature scheduling and the chilly media landscape for national broadcasters may have contributed, but lowish ratings also hinted that the public would catch up with the Olympics at its own pace.

With this new year’s diary switch, the Games of the XXXII Olympiad (24 July–9 August) and the XVI Paralympic Games (25 August–6 September) appeared in plain sight. A wealth of trimmings — days-to-go countdowns, transport ads, hi-tech promotions, festivals, merchandise, books — was making them inescapable. A December poll asking “Is it good for Japan to host the Olympics?” found 86 per cent said yes, 12 per cent no. The most popular reason was “a good opportunity to show Japanese culture to the world.” Tokyo 2020 was nearing the last lap in some comfort.

At that very point came a pebble in the shoe. The circulating respiratory disease 2019-nCoV, at first a down-page story, hit home on 20 January, when the imminent (and routinely welcome) arrival of thousands of Chinese tourists on their new year holiday became mixed with alarm that some high-spenders might prove virus-spreaders. A Japanese coach driver and guide tested positive, as did scores of international cruise-ship passengers quarantined at Yokohama, three elderly Japanese among them dying after disembarkation. Face masks and hand sanitisers sold out. Inevitably, the Olympics entered the frame. Yoshirō Mori, octogenarian head of Japan’s Olympics Committee, gave faltering assurances that the games would go ahead, but virology professor Hitoshi Oshitani and other Japanese specialists are wary.

The first Japanese death, of a posthumously diagnosed woman in her eighties east of Tokyo, came on 13 February. It had no obvious link to Wuhan. This was a second turning point. A recent vogue word, feizu (phase) — as in atarashii (new) feizu or feizu ga kawatta (the phase has changed) — was much used, soon followed by kurasutā (cluster). The mainland incidence of the renamed Covid-19 grew daily, reaching 146 on 25 February (with another 691 on the stricken ship).

Nerves, rightly, are jangling at the prospect of Tokyo 2020 being overtaken on the home stretch. But brains are also in overdrive managing the parallel tests of containing the virus and keeping the Olympics show on the road. Japan’s spring rituals are cutting back: the Emperor’s open day on 23 February, the annual Tokyo marathon on 1 March, school graduations, companies’ welcome to fresh recruits. And more dates are crowding in.

The torch relay of Japan’s forty-seven prefectures starts on 26 March in Fukushima, site of the nuclear meltdown on 11 March 2011 (or “3.11”). Public commemorations of that day’s triple disaster in the Tōhoku region (earthquake, tsunami, nuclear), which took 18,000 lives, will also shrink, as will remembrances of Tokyo’s sarin gas attack on 20 March 1995, which killed thirteen people. Pre-Olympic training and publicity events are thinning (or, for volunteers, going online) and the sense of diminishment is widespread. Abreast of the Olympics, yes, but primarily alert to the lung-attacking illness, Japan’s public is in a very different situation from even a month ago.

For as long as the virus flourishes, the games’ destiny is on hold. Turning back, even scaling down, looks unthinkable given the funds, deals, careers and reputations at stake. It would not be Japan’s decision alone, or even mainly. Covid-19 is mandating big transnational call-offs too: flights, conventions, Formula One. If the Olympics must go because of a worldwide health emergency, they will.

In aggregate, the incipient pandemic and sporting extravaganza presage a global moment. Covid-19 already serves as another topical lesson in the current human system’s fragility, and in the Olympics’ habit of crystallising global uncertainties even as they seek to dissolve them. Even that might not earn the International Olympic Committee, or IOC, overdue scrutiny. But Tokyo 2020 and Japan’s authorities, which own the Olympics’ share of Covid-19’s fallout, can’t long avoid the glare.

At the time of writing, the official Olympics line is unchanged. News and sports bulletins still hug their own track. A Japanese cabinet office poll on 17 February found 36 per cent saying the government is handling the crisis well, 52 per cent not. The government’s latest draft policy, announced on 25 February, focuses on keeping serious cases to a minimum, reducing social mixing and then, as needed, “asking the public to stay indoors.”

Covid-19 aside, insofar as that is possible, a just-completed stay in and around Tokyo has given me an insight into the efficacy of the plans made and messages honed since the 2013 bid was won. That bid, in turn, drew inspiration from Tokyo 1964. Tokyo 2020’s use of these two legacies is also in play now — and even perhaps its link to a third, 1940’s phantom games. That said, the supremely ambitious “recovery Olympics,” its motto “united by emotion,” will not easily be given up. The rest of this article touches on four of the many local aspects of this approaching world story: Tokyo 2020’s concept, locations, hazards and 1964 prototype.

Until Covid-19 hit, Tokyo 2020 had come almost unscathed through its seven-year gestation. There had been bumps on the road, and to say these didn’t deflect progress would only be half true. The other half is that the project raced ahead of them, its eyes on a prize outranking even the games themselves: Japan’s regeneration. The twin affective levers of this strategic purpose were the host city’s magnetism and that clever promotional tag on the 2013 bid: the “recovery and reconstruction Olympics” (soon, the first term was deemed to be enough).

Embedded in the notion was a subtle linkage of domestic and international audiences. The 3.11 tragedy, two years before, was still prominent in the nation’s psyche, while in many international minds it was recalled less for its dreadful images and heartbreaking stories than for the well-reported fortitude and dignity of survivors.

In this context, “recovery” gave Tokyo’s impressive sales pitch — and then its delivery plans — a quintuple kick. It deployed global admiration for Japanese kizuna (solidarity) and energetic voluntarism in the 3.11 aftermath. It positioned the Olympics as a means both to enhance Japan’s global standing and to inject prosperity — largely via tourism — into the country’s less favoured regions, notably Tōhoku itself. It mustered to the cause the omotenashi (hospitality) awaiting visitors. It readied Japan’s domestic sectors, and citizens for the challenges to come.

And the fifth ingredient: it displayed Japan as, in effect, twice over a phoenix nation. Just as Tokyo 1964 was intended to mark a turn from post-1945 pains towards modernisation and international respectability, Tokyo 2020 would be a route from 3.11’s destruction towards a more dynamic economy and a confident, outward-looking country. A parable of redemption from ruination thus bound the two events and eras.

That uplifting story looks most credible in two parts of Tokyo: the Kasumigaoka area of Shinjuku, where a new national stadium designed by architect Kengo Kuma has replaced the 1964 one on the same site, and the giant stepping stones of reclaimed land towards Odaiba, where athletics, tennis and swimming complexes are levers of an even more comprehensive project set to pull this vast city’s centre of gravity to the southeast.

Walking from Sendagaya station in mid January, an early glimpse of Kuma’s feat is the unobtrusive fit of his bowl with its environment. Closer up, a tiered mesh of walkways, timber pillars and greenery brings home his “living tree” designation. Across the road, a new Olympics museum bustles with active seniors and junior high students on school trips. More gather for group photos in the landscaped area outside, whose installations — a popular replica of the Olympic rings, the 1964 cauldron, and statues of the educator-athlete Kanō Jigorō, an Idaten hero, and Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic movement — are a model of spatial-social awareness.

Kanō Jigorō watching over Kengo Kuma’s Olympic stadium. David Hayes

The stadium area is rich in associations with the Meiji era (1868–1912), and nearby gardens, galleries and shrines give it a stately air. By contrast, to walk from glitzy Ginza over the Sumida River’s Kachidoki Bridge and onto Harumi Island — with its construction sites and towering new blocks, huge trucks thundering past on the gaping expressway — is to touch the future (ten minutes after the phrase hit, I disquietingly spotted it on a come-to-buy sign). An immense sky, rare from ground level inside Tokyo’s urban maze, enhances the sense of virgin territory, as does the surrounding water. Ginza, thirty minutes to the north, is already way past.

On Toyosu Island a hi-tech wholesale food market, relocated from creaking Tsukiji in late 2018 after a bitter wrangle, now keeps the tourist and business clocks in more equable sync. Ariake brings the Olympics into fuller view, its gleaming hotels, shopping malls, parks and railway stations as much a showcase as its sports facilities. Tokyo’s southeast flatlands were (like Ginza itself, and Asakusa and Taitō) once synonymous with the pungent culture of the shitamachi (low-lying tenement districts) that made the city’s wares, saw to its daily needs and kept it entertained. That phase in the city’s history is over, its legacy now most palpable in booming nostalgia for the Shōwa era (1926–89).

This airport-strip-like series of artificial islands ends at Odaiba, once fortified to deter any foreign incursion after Commodore Perry’s “black ships” probed Edo (later Tokyo) Bay in 1853–54. An observation deck is well placed to scan the official Olympic rings, which were hauled offshore by a barge on 17 January, as well as the athletes’ village on Toyosu (destined to become apartments), Tokyo’s glittering night skyline and, in the early morning — a kindly guard assures me on a grey afternoon — a beautiful view of Fujisan.

Throngs of amiable international tourists, mostly Chinese, were busily recording the sights, particularly Gundam, a giant humanoid robot. It was a foretaste of peak Tokyo during the northern hemisphere’s high summer. Two days later the Asahi Shimbun was reporting that an “old-fashioned confectionery shop” in the mountain resort of Hakone had already banned Chinese nationals from entering.

That day, the breathtaking scale and detail of Tokyo’s groundwork exuded promise of a mega-event that could well equal Sydney’s and London’s instant acclaim. Yet there was never, on either side of Covid-19, any guarantee of a smooth Olympics landing.

For one thing, the trek has been bumpy, even by host cities’ usual standards. The late architect Zaha Hadid’s florid stadium proposal was annulled in favour of local hero Kuma, to a many-sided uproar in the profession. (“The government is skilfully manipulating the public’s xenophobia,” said Arata Isozaki, who had nonetheless called Hadid’s design “a turtle waiting for Japan to sink so that it can swim away.”) An emblem design was replaced after plagiarism charges. Japan’s previous Olympic Committee president resigned over vote-buying. The ticket lottery and volunteer systems were skewed. Mounting costs fuelled regional ire over Japan’s Tokyo-centricity.

Tokyo’s Odaiba precinct. David Hayes

The IOC, like FIFA and other sporting hegemons an unaccountable nexus of commercial and political power, floats above all this: secure in its lucrative commercial deals, outsourcing of costs to the host, exclusion of local businesses from the jamboree, and covetous ticket allocations to members, family and cronies. On the big picture, the University of Lausanne’s Emmanuel Bayle, writing in 2019, is lethally restrained:

[There] are still no real international checks and balances on the governance of the IOC or the [International Sports Federations] within an Olympic System that now includes numerous stakeholders. Given the growing financial importance of the Olympic phenomenon and the Olympic Games, improper conduct, including poor governance, corruption, worship of mammon, doping and the use of sport to further geopolitical or economic aims, has the potential to severely damage the reputations of the IOC and organisations belonging to the Olympic System.

For another thing, these base mishaps and lockdowns join a high gambit shared by the IOC and Japan long before Covid-19 was heard of: the very decision to hold the Olympics and Paralympics in the country’s hot and humid summer, which is also its usual typhoon season. The 1964 games took place in October, safely beyond (as it happened) a torrid summer of water shortages. Today, American NBA and European soccer schedules, holy to sponsors and broadcasters, make such a diary shift unthinkable.

One peril of the wager is a repeat of October’s immense Reiwa 1 East Japan Typhoon, or Hagibis, the fourth such calamity in Japan since July 2018. Such typhoons’ increasing frequency and power is leading to “a major shift in Japan’s disaster policy,” says Koji Ikeuchi, Tokyo University professor of civil engineering and expert in water-related disasters. Hagibis forced the cancellation of three matches in rugby’s world cup, which pales against the ninety-eight deaths it inflicted, although the competition, spread nationwide to droves of enthused niwaka (overnight fans), absorbed the damage with an uplifting mix of brio and respect for the victims.

The same university’s Earthquake Research Institute works on the basis of a 70 to 80 per cent probability of a mega-quake by 2050 in the Nankai Trough, a Pacific Ocean trench under much of southern Japan. Tokyo itself may be more resilient than in 1923, its plans to cope elaborate, but its vulnerabilities — including its below-sea-level southeast’s exposure to storm surges — are a fact. The inner earth sends frequent reminders. The effects even of Ibaraki’s magnitude 4.8 quake at 2am on 1 February shook this non-tyro foreigner. “The ground is adjusting,” said one of my Japanese family, lightly, in the morning.

A dispute over health pressures on endurance athletes pushed the IOC, to its credit, to transfer marathon and race-walking events to Sapporo, the main city of Hokkaido on Japan’s northern island. There, July temperatures are on average five to six degrees cooler than Tokyo’s. “A painful decision, not an agreement,” protested Yuriko Koike, Tokyo’s mayor. This climate-related concession leaves the outdoor program more than usually exposed to extreme heat and humidity.

Japan’s national tourist association expects forty million visitors in Tokyo’s greater metropolitan area during the events. Measures to alleviate any discomfort include free ice cream, artificial snow (the real thing is getting scarcer), heat-blocking road surfaces, and shade trees. The IOC entourage might not need those: its Tokyo base is — where else? — Ginza’s Imperial Hotel.

For all these hurdles and pitfalls, opposition has been relatively muted. A spate of books in 2013–16 assailed the choice of Tokyo, and anti-Olympics pressure groups such as Hangorin no Kai (No Olympics 2020) sprang into life. Resisting the inevitable became harder as the post-Rio juggernaut got into gear and prime minister Shinzō Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party cruised towards its third landslide in five years. But critics such as the indefatigable sports journalist Gentaro Taniguchi — whose new book says the Olympics “are at the mercy of commercialism and nationalism” — and the tabloid Nikkan Gendai newspaper continue to carry a dissident torch.

Tokyo 2020’s confidence, meanwhile, grew with each passing hitch. At its core is that parable of rebirth from rubble, a chain that goes beyond 3.11 to Tokyo 1964 — a future-oriented event that was only later seen in cyclical relation to Tokyo 1945 and the terrible fire-bombing that razed it and dozens more Japanese cities.

From the start, Japan’s second summer games have drawn heavily on the moral capital and potent symbolism of the first. The latter’s five-year run-up was politically febrile, but Tokyo 1964 turned out to be a landmark in the nation’s history. What made it so, above all, was that an unrepeatable psychic and experiential mix brought Japanese people, collectively and in their individual millions, to an (albeit complex) emotional release.

Such is the kernel of a tremendous NHK documentary, the fifteenth in its A Century in Moving Images series. Its archive footage of Tokyo’s pre-Olympics mania of demolition and construction depicts the capital as reeking, jammed, litter-strewn — and parched. Four months before the games, only 2.2 per cent of Tokyoites named them as a top priority, while 59.2 per cent said other issues (above all, a water shortage) were more important. With two days to go, the heavens burst: a cleansing typhoon.

Optimism took flight with sporting success, Japan’s sixteen golds earning third place in the medals table. Further buoyancy came from displays of popular enthusiasm, from avid crowds on the torch and marathon routes to the finale’s unexpected happy chaos. Athletes mingled and hearts melted to a mass chorus of the school graduation tear-jerker “Hotaru no Hikari” (“Light of Fireflies”), Japan’s emperor doffing his hat when a Kiwi athlete blew him a kiss.

The imprint of Japan’s 1937–45 wars is everywhere in the NHK series, as a marker of closeness and distance alike. Yoshinori Sakai, born in Hiroshima prefecture ninety minutes after the atomic bombing, lit the Olympic flame in 1964. Tadashi Matsudaira, engineer on the Tokyo–Osaka (Tōkaidō) Shinkansen, launched days before the games began, had worked on the navy’s wartime Zero attack planes. The novelist Sonoko Sugimoto, aged eighteen, heard prime minister Hideki Tojo address a mass rally of conscripted students on the same stadium site in 1943. (“Today is also connected to the past. I feel fearful of that fact.”) Hirobumi Daimatsu, oni (demon) coach of the women’s volleyballers who won gold against the Soviet Union, had survived the 1944 battle of Kohima; he played driving father to the textile factory team, several of whom had grown up without one, and later go-between.

Many intellectuals, including Yukio Mishima and Yasushi Inoue, were moved by the Olympics experience. (Kodansha’s instant collection of writers’ responses was republished in 2014.) The novelist Hitomi Yamaguchi, who saw in the marathon a spirit of human fellowship, had another epiphany when the hinomaru (national flag) was hoisted after Japan’s great hope Kōkichi Tsuburaya took bronze in the race. “For the first time since the war I could see the flag raised without any dejection. With no hesitation, a good feeling. Tsuburaya-kun, arigato!”

But Tokyo’s frenzied makeover, with its many ravages, led Akiyukii Nosaka and Takeshi Kaikō (Kaikō Ken) to ambiguous self-reflection. Only now that old neighbourhoods are gone, and links to a discreditable past broken — wrote Nosaka, with a hint here of his own — is it possible to look back without shame: a “half improvement.” Kaikō’s year-long reports for Asahi Weekly, often featuring the low-paid, insecure workers sweating to finish behemoths on time, concluded with one titled “Sayonara, Tokyo.” A fragmented city had become a mirror of his own anguish: “Walking around Tokyo, the more I knew the less I could understand. Just asking continually is the only answer — that’s all I can say.”

Tokyo 1964’s great dramas and intense emotions, understandably shorn of complexity, define its place in public memory. For 3.11, the agony of human loss and destruction does the same. Tokyo 2020 seeks to honour the two moments, in the latter case with gestures of symbolic inclusion at every stage during the games and by delivering promised reconstruction afterwards.

Astute as the prospectus is, its tone can’t help but imply that Tokyo 2020, even before it has happened, transcends these unique and dreadful precedents (and not only because it comes later). Its driving aim sounds assimilative, its wreckage-to-riches tale prescriptive, its insistent amity cloying. Its very seamlessness recalls the critic Jun Etō’s take on postwar censorship under American occupation: “a closed linguistic space.” There is a lack of humility. In the apt Irish phrase, Tokyo 2020 has lost the run of itself.

Tokyo 2020’s slick fusion of utility and piety has always left room for a scepticism that — like the many waterways buried in concrete by the first Olympics — runs deeper than mere opposition. In Kōtō-ku library, above a room lovingly devoted to film director (and local boy) Yasujirō Ozu, I came across a rich photographic record of 1964 in Tokyo, published in December by the Japan Press Research Institute and Kyodo News. The editor’s then-and-now reflection is pointed, even moving (and the last word, having come to it independently days earlier, was stunning to read):

The Japanese people [in 1964] were overwhelmed by the competition from foreign athletes. They had a feeling of yearning and a renewed sense of patriotism, while suffering from an inferiority complex about their backwardness… [Japan on the eve of 2020] is becoming more confident of its national power and sports. But Japan has lost a sense of freshness, dedication and humility.

More sweeping is the verdict of an acquaintance, a civil engineer in his fifties, who in lucidly cynical English cites a litany of reasons why Japan “has no need” for the Olympics now. As we talk in Ōmiya’s beautiful new public library, across the border in Saitama prefecture, T-san holds responsible a government with “no strategy, direction, vision,” and an “anachronistic” education system that holds young people back. The accursed games are, in this view, the epitome of a wider national and civic malaise.

Such bleakness could turn out to be justified without being vindicated. John Rennie Short skewers the IOC cohort’s fourfold “event capture” (infrastructural, financial, legal, political) that traps hosts even as they promise their citizens a new dawn. The post-Olympics backlash tends to take hold a year later, as debts mount, scams leak and memories fade. Its own passing can, in some cases, rekindle the original glow. Tokyo 1964’s homegrown hangover included a spate of bankruptcies, political imbroglios and environmental scandals. Yet its reputation soars above them. Tokyo 2020 could, assuming it delivers the initial goods, extend the pattern. The Olympic dream machine grinds facts, and critics to dust.

More immediately for Tokyo 2020, everything depends on Covid-19’s course. Nothing is foreordained — or foreclosed. The soon-to-be-pandemic, expanding in Iran, Italy and South Korea, continues to reset plans and minds in Japan. One plausible scenario is that a call-off becomes imperative as grim diagnostics rally an international bandwagon of competitors. Another, were a path to the games to be cleared, is that Tokyo 2020 audaciously enfolds the virus’s retreat into the “recovery Olympics” tale. A third, darker vista was seeded prior to the infection’s surge, in a tech store I visited where licensed Olympics merchandise adjoined disaster prevention goods. If they were to overlap during the games, Tokyo 2020’s mighty edifice would not escape the damage.

If it is to be the first, quick is best. If the third, preparing and praying will have to do. For everyone’s sake, sportspeople and worldwide niwaka foremost, the second must be devoutly hoped for. Let it be a great Olympics — and the last in this form. Neither Japan nor anyone else should indulge the IOC and its kind any longer. Once, under the station rafters, Miyahara’s elementary school students “put paid to fate, it abdicates.” Now, monsters of the year are regrouping. Those who would be on the angels’ side need seriously to raise their own game. •