The Trials of Portnoy: How Penguin Brought Down Australia’s Censorship System

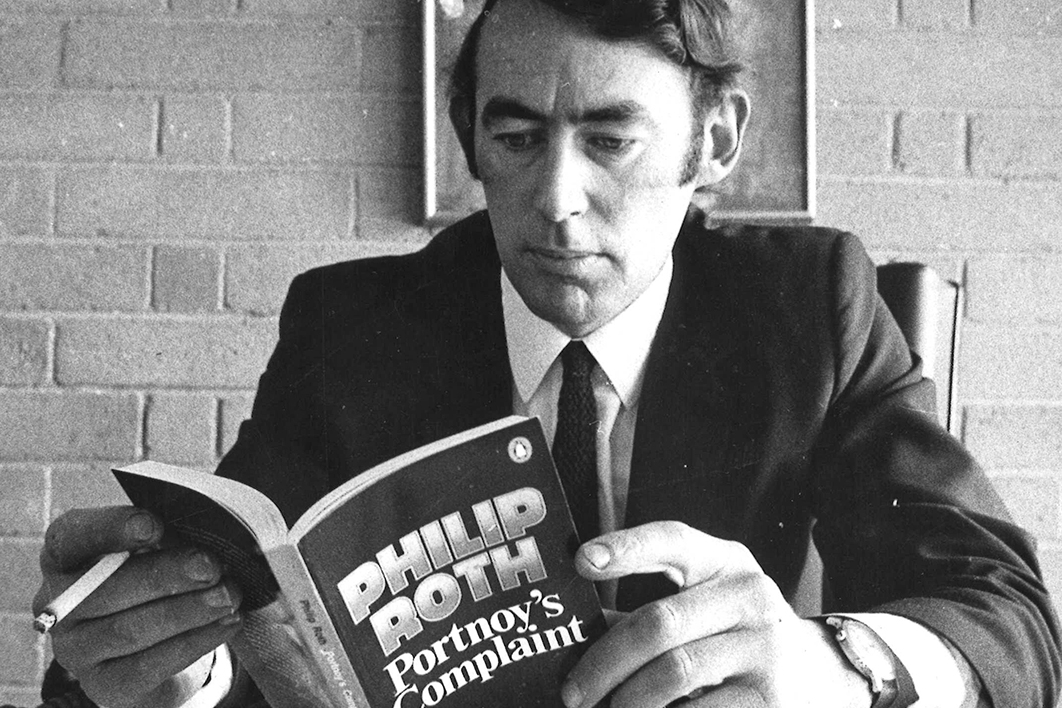

By Patrick Mullins | Scribe | $35 | 336 pages

In August 1970 thousands of copies of Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint were printed and distributed in absolute secrecy to booksellers and wholesalers across Australia. “It was like the Germans going into Poland in 1939,” observed John Hooker, Penguin Australia’s New Zealand–born publisher. The great test of Australia’s censorship regime was in motion. By the end of 1972 the system would be in tatters.

Patrick Mullins is the recent winner of the NSW Premier’s Douglas Stewart prize for his previous book, Tiberius with a Telephone: The Life and Stories of William McMahon (Scribe, 2018). His new book takes us on a fascinating journey through the final years of Australia’s literary censorship system, deftly telling the story of the many obscenity trials prompted by sales of Roth’s controversial novel in this country.

Australia’s censorship regime was a complex one, involving federal and state mechanisms designed to prevent offending books from being published, sold and circulated. Dating back to the late nineteenth century when the novels of Émile Zola, Honoré de Balzac and Guy Maupassant were considered too racy and radical for the Australian reading public, the multilayered system grew especially fierce through the interwar period. As Nicole Moore shows in her 2012 book, The Censor’s Library, the system brought together the customs system, postal regulation and various other legal mechanisms. The federal government had also added a Literature Censorship Board, on which a mix of scholars and bureaucrats determined the fate of books.

Many books had been banned from importation from the 1930s to the 1960s. They included Radcliffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928), D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1929), Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), Kathleen Winsor’s Forever Amber (1945), J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1953), Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place (1959), and James Baldwin’s Another Country (1962). Locally, Norman Lindsay’s Redheap (1930) was among the books placed on the prohibited list.

Sex was the main objection — especially anything suggestive of “deviant” sexuality, which at the time was considered to include homosexuality, masturbation, obscene language, pornographic scenes and sex without consequences. But radical politics was also suspect, as was contempt for religion. Proponents of censorship believed that people needed protection from the corrupting and depraving effects of such material. Scholars have shown how the system created a culture that was conservative, timid and quarantined from intellectual and cultural influences flourishing abroad. As Dymphna Cusack concluded when her own book (written with Florence James) Come In Spinner (1951) could only be published with severe cuts, Australians were basically wowsers.

By the time Portnoy’s Complaint came along, resistance to censorship was growing. Occasional challenges had been launched and voices raised in opposition since the 1930s. By the 1950s, many books had been removed from the banned list on the basis of their literary merit. But the 1960s was the decade that really saw a concerted effort to overturn the system. The student and radical alternative press — which included magazines such as Oz — aimed to provoke reaction by testing its boundaries. Plays like Alex Buzo’s Norm and Ahmed (1968) began making use of offensive language. But the real test came with the Australian publication of a controversial novel by an American writer.

Portnoy’s Complaint is written from the point of view of Alexander Portnoy, a sexually frustrated young man narrating his erotic experiences to his psychoanalyst. There are a great many descriptive scenes of masturbation in the novel; a memorable one (often cited by the prosecutors in the trials) involved Portnoy masturbating into a piece of liver that his mother then serves for dinner. Roth also made use of a litany of obscene words to punctuate his text, including such profanities as “fuck,” “cunt” and “prick.” The book was a sensation, and the US critics praised its originality and creativity of language.

But was Australia ready for such a book? The Literature Censorship Board, divided as to whether Portnoy could be allowed into Australia on the basis of literary merit, decided to ban it. Outraged, many Australians, including publishers and the literary community, resolved to have the decision overturned.

The censorship regime was already wobbling. Politicians were divided over its effectiveness, especially given emerging differences between federal and various state views. The appointment of a relatively young MP, Don Chipp, as customs minister seemed to offer the possibility of a more liberal approach. But although Chipp was sympathetic to critics of censorship, many in the community still supported the system. Portnoy was going to remain banned.

And so began Penguin’s campaign. With great speed and secrecy, Portnoy was printed and distributed across the nation. Once it went on sale (usually from behind the counter rather than openly displayed), it sold out almost immediately. Enforcing the ban was in the hands of state governments, though, and this is where things started to go wrong for the censors. South Australia, under Labor premier Don Dunstan, declined to prosecute as long as the book wasn’t on view, a decision that revealed a lack of unity among the states from the start. But other states raided bookshops and proceeded to take booksellers to trial.

A significant part of Mullins’s book is devoted to describing the trials, and they make for entertaining reading. Prosecutors did what they could to demonstrate the offensive nature of Portnoy: in the Victorian trial, for example, they contended that sexual references and four-letter words appeared, respectively, on 28.1 per cent and 17.5 per cent of the book’s pages. In the NSW trial, prosecutors tried desperately to prove that the book was being sold to schoolgirls, yet they couldn’t produce proof it had actually happened.

Witnesses for the defence made up a who’s who of Australian literary and academic circles: Patrick White, Stephen Murray-Smith, Nancy Keesing, T.A.G. Hungerford, Alec Chisholm and Dorothy Hewett were just some of them. All testified to the literary merit of Portnoy. Patrick White commented on the stand that he had no problem with “fuck,” “cunt” or “prick” as he used such words himself, daily. After his cross-examination at the second NSW trial, he wrote to publisher and writer Geoffrey Dutton: “the prosecutor [P.J. ‘Jack’ Kenny, QC] I can only describe as a cunt.”

The trials would ultimately have mixed results. In Western Australia, the book was found to be obscene but also to have literary merit, and so it could be sold. In Victoria, the verdict went against Penguin, but an appeal was lodged. In New South Wales, the courtroom drama dragged on: two trials were held, but no verdict was reached. Shortly after NSW authorities decided on 28 May 1972 not to go to a third trial, Chipp took Portnoy off the banned list. In December, Gough Whitlam and Labor won office and the old censorship regime was swept away in favour of a classification system. Literary works would not be in the firing line again, at least not because of sex and four-letter words.

Mullins’s compelling account of these last days of the old censorship regime skilfully draws on a rich range of sources, including interviews with many of the key figures involved. He gives an insight not just into how the system operated and the politics involved, but also into a significant cultural moment in Australia.

Australian publishers were beginning to flourish in this period. While the case centred on an American novel, Penguin was establishing itself in Australia as a publisher of both imported and homegrown literature. A more diverse Australian cultural and literary scene would result from the work of such publishers as well as the lifting of stultifying censorship.

The Trials of Portnoy is a very welcome contribution to the small but significant literature about the history of censorship in Australia. While Mullins chooses, perhaps wisely, not to weigh in with any reflections on current, all too complex, questions raised by “cancel culture,” no-platforming and other limits on freedom of speech, this book provides some much-needed context for thinking about the issues raised by controversial and offensive material.

While we will likely never see this kind of literary censorship again in Australia, we should not assume that our creative and intellectual freedoms will always be protected. Nuanced discussions about the meanings of such freedoms are vital — as is thinking about how best to balance them against the damaging impact of discriminatory language, hate speech and other expression that might offend some members of the community. •