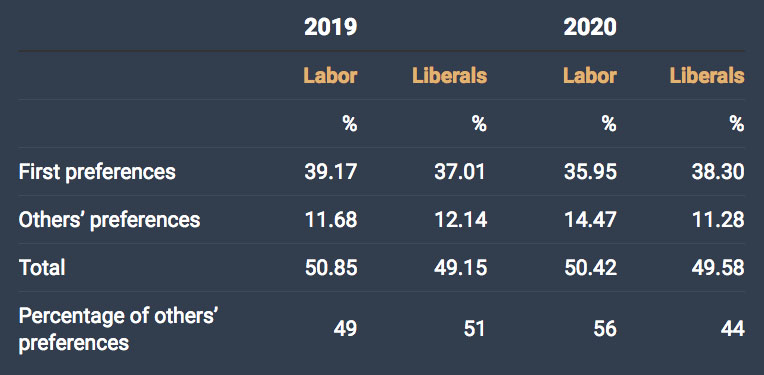

The key to what happened in Eden-Monaro lies in a marked shift in preferences. Last year, even with the well-regarded Mike Kelly as local member, Labor won only 49 per cent of the preferences of the smaller parties: Greens, Nationals, micro-parties and independents. In Saturday night’s counting, it won 56 per cent.

Had the preference split on Saturday night been as it was in 2019, the Liberals’ Fiona Kotvojs would have won the seat easily. On first preferences, her vote rose 1.35 per cent and Labor’s fell 3.2 per cent. If that were all that happened, Kotvojs would have won by more than 3000 votes.

But it wasn’t. Most of the votes Labor lost on primaries came back to it as preferences. Most of the votes the Liberals gained on primaries were lost to it in preferences. That’s why Labor’s Kristy McBain will end up winning the seat by somewhere between 500 and 800 votes. That’s close, but winning is what matters.

In Australia, first-preference votes don’t decide elections; despite ignorant comments from some journalists who should know better, what matters is the result after preferences. We abandoned the first-past-the-post system a century ago. Since then we’ve voted preferentially — and it was the shift in preferences that decided Eden-Monaro 2020.

The 2019 election had a field of eight: Labor, Liberals, Nationals, Greens, two small parties of the right (Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party and Fred Nile’s Christian Democrats) and two independents. The first two columns of figures show how it went.

The preferences from left and right largely cancelled out: 87 per cent of Greens voters gave their preferences to Labor, 87 per cent of Nationals voters gave theirs to the Liberals. The Liberals did slightly better overall on preferences, but not enough to challenge Kelly’s lead on first preferences.

Compare that with the 2020 vote as of Monday night, as shown in the third and fourth columns.

The question is, why did the preferences shift?

On Sunday, the losing Liberals blamed a scarcely veiled hint last week by the Nationals’ NSW leader John Barilaro that his party’s supporters should direct their second preferences to the Labor candidate. They claimed that 20 per cent of Nationals preferences flowed to Labor, compared with 12.8 per cent last time.

If true, that alone would have swung almost 0.5 per cent of the vote Labor’s way — more than the 0.42 per cent it now leads by — and cost the Liberals the seat. But Nationals sources on Monday say their scrutineers reported Labor getting only a little over 10 per cent of their preferences. It will be weeks before the Australian Electoral Commission releases official figures that will show us which Coalition partner to believe.

More on Barilaro in a moment. But there are two other reasons why Labor ended up with such a big haul of preferences this time, and the mainstream media has ignored both of them.

First, ten minor-party candidates and independents were on the ballot paper, a big change from four last time. Five of them (none of whom stood last year) directed their preferences to Labor. Four were formally neutral, but they included HEMP (Help End Marijuana Prohibition), which won 2.3 per cent of votes, and Sustainable Australia, on 1 per cent. Apart from the Nationals, only the Christian Democratic Party directed preferences to the Liberals.

Of course that is going to change first-preference votes. It’s a fair bet that most people who voted for HEMP would otherwise have voted for the Greens or Labor. Probably the same is true of Sustainable Australia and the Science Party. Their presence on the ballot paper meant that the first-preference votes for Labor and the Greens would fall.

But that has no impact on the result. People who voted for those parties will still ultimately choose between Liberal and Labor on their ballot paper, and there’s no reason to think that voting for HEMP or the Science Party first changes that ultimate preference. When the number of candidates expands, the bigger parties (including the Greens) lose first-preference votes, but they come back to them when preferences are distributed. (For those interested, I discussed this further here in 2016.)

Conversely, while the Liberals’ primary vote jumped 2.35 per cent, almost all of that was offset by the loss of preferences from the Palmer party (which no longer exists), as well as the Nationals and the Christian Democrats (whose votes fell as the Liberals rose). That’s why Kotlojs ended up with just a 0.4 per cent gain in her two party preferred vote. And that is the vote that decides the outcome.

Second, among the eight new entrants, the big one was the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, which already holds three seats in the NSW Legislative Assembly. It drew first spot on the big ballot paper, won 5.4 per cent of the vote — and told its supporters to give their preferences to Labor.

How many did so remains to be seen. Its candidate, Matthew Stadtmiller, stood in Cootamundra in last year’s state election, and 51 per cent of his distributed preferences went to the Nationals. At the federal election, 59 per cent of all Shooters’ party preferences went to the Coalition. Stadtmiller has estimated that this time about 60 per cent of his preferences went to Labor.

Maybe, maybe not. I happened to be driving home through Eden-Monaro on Saturday, admittedly in the coastal and southern part of the electorate, and I saw no one handing out how-to-vote cards for the Shooters, or any micro-party or independent for that matter, at any of the four polling booths I passed. We know that most voters don’t follow any how-to-vote card exactly. Again, we will have to wait for the official figures from the AEC.

But the central theme of the stories reverberating from this status quo result will be the ambitions of John Barilaro. When Mike Kelly announced his retirement, Barilaro was quick to declare his interest in the seat. It includes all of his state seat of Monaro, as well as most of Bega, held by the Liberal transport minister Andrew Constance, and some new territory to the north and west, such as Yass, Tumut and Tumbarumba. The Nationals whipped up an instant poll that suggested he would win it if he stood.

I suspect the poll was right. Barilaro has been an electoral phenomenon in his area. In 2011, he rode the Coalition wave to unseat a popular Labor MP, Steve Whan, and over three elections he has increased the Nationals’ two-party vote from 43.7 to 61.6 per cent, despite a falling Coalition vote elsewhere. The voters out there like him. At last year’s state election he won every booth in the electorate, even in Queanbeyan, which traditionally votes Labor.

And in quick time, Barilaro had also become the Nationals’ NSW leader. If he was moving into federal politics, he would assuredly not be expecting to be kicking his heels on the backbench. With Michael McCormack clearly vulnerable as Nationals leader, one could assume that Barilaro had his eyes on becoming the party’s national leader. He’s the tough old-style leader they’re used to.

At federal level, though, Eden-Monaro has never been the Nationals’ turf. And even though Constance had announced plans to retire from politics, someone in the Liberal Party elbowed him to declare that he too was interested in the federal seat. The spectacle of two senior Berejiklian government ministers clashing head-to-head was too much. Barilaro pulled out of the contest, and surprise, surprise, the next day Constance did too.

Barilaro was angry, as was revealed when someone leaked his unflattering emails to McCormack. His interventions in the final days — blasting the Morrison government’s cuts to the ABC, revealing that he had given his preference to Kelly in 2019, and effectively urging Nationals voters to give their preferences to McBain in 2020 — suggest he was hoping that Labor would hold the seat. We can presume that he wants to have another shot at it in 2022.

This story will run on, particularly if the AEC’s figures eventually reveal that the shift in Nationals preferences this time was large enough to have given Labor the seat. Watch this space. •