On the morning of 19 September 1940, eighty years ago this week, HMAS Adelaide arrived in Noumea, 1500 kilometres off the coast of Queensland. Following Germany’s blitzkrieg advance across Europe and the occupation of Paris, the Australian warship had been sent to New Caledonia to support a local revolt against colonial authorities who favoured the new Vichy regime in France.

Five weeks earlier, Australia had sent its first diplomat to the Pacific islands seeking information about the level of support for Charles de Gaulle. The London-based Free French leader had called on France’s overseas possessions to rise up against the collaborationist regime led by Marshal Philippe Pétain.

It was a crucial time in the relationship between Australia and one of its closest Pacific neighbours, and this history of mobilising defence and diplomacy against a rising Asian power has echoes today.

The path to war during the 1930s had already transformed colonial relations in the Pacific. Facing US embargoes, Japanese militarists looked south to the oil resources of Southeast Asia and to strategic mineral deposits throughout the Pacific islands. New Caledonia’s massive reserves of nickel were also coveted by Germany, and the Japanese had increased their investment and trade with the French colony. From 1933, the fascist powers even began to manufacture solid nickel coins as a way of stockpiling this crucial resource for arms manufacture.

But Japan’s 1931 invasion of Manchuria and the 1937 Sino-Japanese war raised fears of a wider regional conflict. With war raging in China, anti-fascist trade unionists in Australia blocked shipments of slag metal to Japan in late 1938, to the anger of attorney-general Robert Menzies, known forever after as Pig Iron Bob.

Long before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, some French officials in New Caledonia had tried to limit the sale of nickel to Tokyo, fearing it would be onsold to Nazi Germany. By 1940, Australian officials were negotiating with New Caledonia’s largest producer, Société Le Nickel, to purchase nickel as a way of encouraging the French colony to cease exports to Japan.

Australian politicians had been promoting a policy of “strategic denial” in the Pacific since long before Federation. At the start of the second world war, with Britain and France entangled in the European conflict, the Royal Australian Navy needed more information about political developments in strategically important New Caledonia.

Naval historian Ian Pfennigwerth has documented RAN intelligence operations at the time. “Director of Naval Intelligence Rupert Long had organised some human intelligence sources in Noumea,” he writes. “He had arranged to have William Johnston appointed as Admiralty Reporting Officer Noumea on 15 April 1940. He had also organised through Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Denis, the French military commander in Noumea, that a French naval officer would provide the Naval Intelligence Division with intelligence.”

Anxious to get more of its own information independent of the British, the Australian government decided in mid July 1940 to send a French-speaking lawyer, Bertram Ballard, to Noumea to observe and report back.

Eighty years on, Ballard’s successor as Australia’s representative in New Caledonia is consul-general Alison Carrington. Last month she organised a ceremony in Noumea to commemorate the arrival of Australia’s first diplomatic representative in the Pacific islands.

“This year, we’re celebrating eighty years of an official Australian presence here in New Caledonia,” she tells me. “The nomination of Ballard was quite an important moment: it represents our fourth diplomatic mission overseas. Before Noumea, there was only London, Washington and Ottawa.”

Bertram Ballard had previously served as Australian government solicitor in neighbouring New Hebrides (today, the Republic of Vanuatu). The government’s decision to send him to New Caledonia followed Charles de Gaulle’s famous 18 June call for French overseas colonies to rally to a Free France. “New Caledonia hadn’t actually done that,” says Carrington, “so Ballard’s mission was to come to Noumea, report on political and economic matters and basically take the temperature of the place during this time of global upheaval.”

With the Germans having occupied Paris, New Caledonia’s governor, Georges Pélicier, an ageing colonial civil servant, was wavering between supporting the exiled Free French forces or Marshall Pétain’s regime, headquartered in the French spa town of Vichy. The governor angered Gaullist supporters in Noumea when he published Vichy’s new constitutional laws on 29 July.

Pélicier had asked the Vichy regime to send a warship to Noumea, and it deployed the vessel Dumont d’Urville from French Polynesia in late August, commanded by Toussaint de Quièvrecourt. The French aristocrat, a fervent colonialist, reported to Paris that Australia was subsidising local Free French agitators with the objective of annexing New Caledonia.

A month after he arrived in Noumea, Ballard wrote to Canberra reporting that most New Caledonians would “welcome and follow” a governor appointed by de Gaulle. As Alison Carrington explains, until Australia had someone on the ground in Noumea “we weren’t aware of quite the level of support for Free France here. I like to think that having an official representative on the ground at the time contributed in some small way to assisting the decision to send HMAS Adelaide to escort Henri Sautot into New Caledonia, which ultimately led to New Caledonia rallying to Free France.”

Sautot was French resident commissioner in the neighbouring Condominium of the New Hebrides, which had been jointly colonised by France and Britain. With British support, Sautot had rallied French colonists in Port Vila to support the Gaullist cause. After extensive debate, the Australian government decided to transport Sautot to Noumea, deploying HMAS Adelaide as protection.

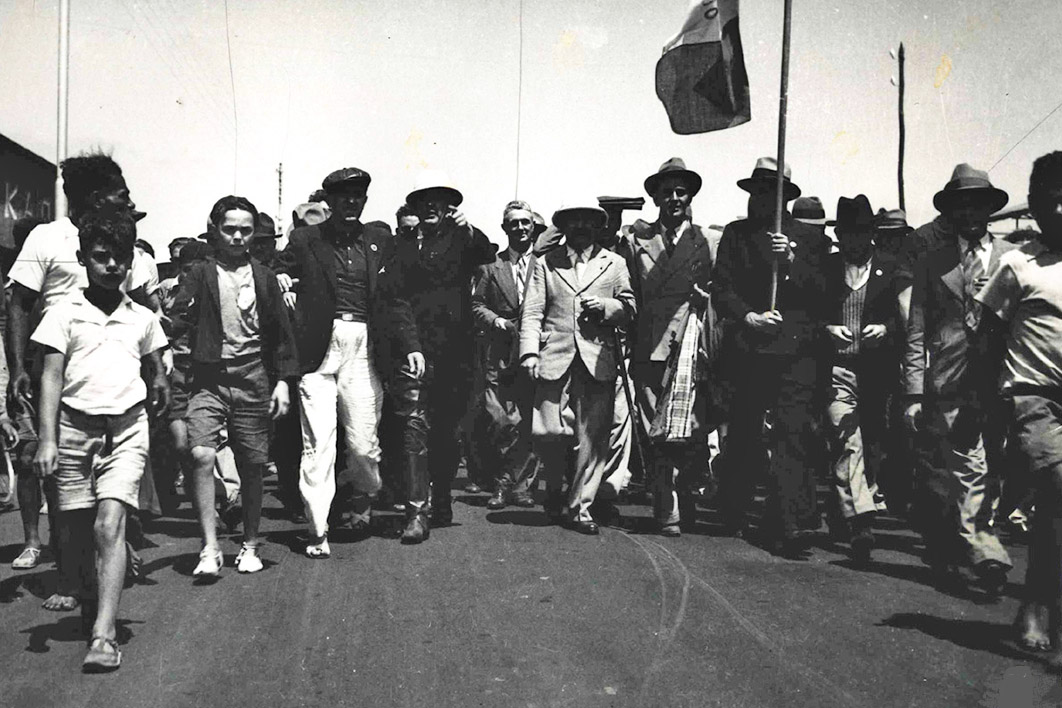

John Lawrey’s classic study, The Cross of Lorraine in the South Pacific, documents this successful episode of gunboat diplomacy. The Australian warship, under the command of Captain Harry Showers, escorted the Norwegian ship Norden from Port Vila to New Caledonia, with Sautot aboard. Arriving in Noumea early on 19 September, Showers was under orders not to fire unless fired on by the Dumont d’Urville or French army shore batteries. Facing off against the French ship, Sautot was transferred from the Norden onto the Australian warship. A popular uprising was under way onshore.

An uneasy days-long stand-off ended with the Free French forces prevailing under the watchful eye of the RAN warship. Following an unsuccessful revolt by pro-Vichy officers on 23 September, Ballard and Showers convinced Governor Sautot to arrest the remaining pro-Vichy leadership. To forestall any further trouble, Showers drafted a letter for Sautot to send, inviting Dumont d’Urville to depart. The French ship soon left port, carrying pro-Vichy officials to Saigon in French Indo-China.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, an Australian commando company was deployed to New Caledonia to train “native scouts” for a guerilla campaign against an invading Japanese force. From 1942, Noumea was transformed by the influx of tens of thousands of American troops, preparing to fight their way across the Pacific islands towards Japan.

These tumultuous events inspired a young Australian to write his first book. Hailing from the small town of Poowong in the Victorian farming district of Gippsland, Wilfred Burchett visited New Caledonia in 1939 and 1941. He travelled throughout the islands, gathering stories from a range of ordinary people — nickel prospectors and Javanese mine workers, Kanak villagers and French farmers.

Published in 1941 as Pacific Treasure Island, Burchett’s words from eight decades ago still resonate today, as New Caledonia strengthens ties with Australia and the Pacific region. “Whatever the fate of the French empire,” he wrote, “it is certain that relations between New Caledonia and its Pacific neighbours will become ever closer, and it is high time that all we Pacific neighbours began to know each other a little better.”

This perception of Australia and New Caledonia as neighbours was uncommon in the 1940s. Since then, community contacts between the two neighbours have ebbed and flowed through periods of cooperation, exploration and mutual suspicion.

From the mid 1970s, as Papua New Guinea gained independence and ni-Vanuatu battled Britain and France in the New Hebrides, some Australians engaged with Kanak cultural and political activists. Links expanded through unions and ecumenical church networks, regional sporting competitions, cultural exchanges and the thousands of young Australians who travelled to study the French language.

Even before the founding in 1984 of the independence movement Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste, or FLNKS, Kanak leaders such as Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yann Céléné Uregei visited Australia to lobby for government support. Between 1984 and 1988, trade unions, churches and community groups supported the Kanak independence struggle through the period of violent clashes known as les évènements.

As New Caledonia descended into armed conflict, friendly relations between Canberra and Paris disintegrated. France’s ties with the Pacific Islands Forum were already strained because of regional opposition to French nuclear testing. The 1985 bombing of the Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior by French intelligence agents and the deployment of thousands of troops to New Caledonia in 1986 won France few friends, in the region or internationally.

Australia reluctantly followed Island Forum countries to support New Caledonia’s return to the UN list of non-self-governing territories in December 1986. In retaliation, France suspended ministerial visits and expelled Australian consul-general John Dauth from Noumea in early 1987.

Those diplomatic dramas are long past. French nuclear testing ended in 1996; two years later, the Noumea Accord mapped a path to possible New Caledonian independence via political devolution. This transformed France’s profile in the region and ties to Australia.

“Today, we have a very good relationship with Australia,” New Caledonia’s president, Thierry Santa, tells me. “We’re developing many commercial activities because we have a good bilateral relationship. As a government, we’ve undertaken a number of visits to Australia, but the economic discussion is happening more at the level of the states. On the health front, Australia remains the primary location for medical evacuations from New Caledonia. In education, we have a number of agreements for students to move in both directions. So relations are really great.”

Over the past decade, even as independence movements in New Caledonia and French Polynesia continue to call for an end to French colonial rule, Paris has improved its diplomatic relations in the islands region. The government of New Caledonia is also basing delegates in French embassies in Canberra, Wellington, Port Vila, Port Moresby and Suva.

A key turning point, according to Australia’s Alison Carrington, was the decision by regional leaders to include the two French dependencies as full members of the Pacific Islands Forum in 2016.

“This decision really marked an evolution of the relationship for these two Pacific territories more broadly in the region,” she says. “This is something that both France and Australia strongly encourage and endorse: the increasing participation of the French Pacific territories in the Pacific region, the neighbourhood we all share.”

The consul-general says she is seeking to expand cooperation with Australia in agriculture, mining services and especially education.

“More and more Australians are aware that New Caledonia is just a stone’s throw from our east coast,” she says. “Because of that geographic proximity, for a long time there’s been a lot of back and forth between Australia and New Caledonia, for holidays, for work or study. New Caledonians young and old have been travelling to Australia to study English, some to do their primary and secondary schooling, many to study at universities in Australia. In the other direction, New Caledonia represents the closest and easily accessible place for Australians to come and enhance their French-language skills.”

Where wealthy New Caledonians once travelled primarily to France for holidays, by 2010 Australia had become their top destination. “There is a strong flow of tourists headed in the direction of Australia,” Carrington acknowledges. “The number of tourists who come from Australia by plane to stay in hotels is a bit smaller, and that is something that New Caledonian authorities seek to grow. But before Covid, we were welcoming around 300,000 Australian tourists a year on cruise ships.”

Trade between Australia and New Caledonia amounted to $721 million in 2018–19. But that year, China was the number one export destination for New Caledonia, with 31.7 per cent of trade, followed by Korea and Japan — rankings that reflect exports of nickel ore and ferronickel metal. Australia had been a primary export market for nickel ore until rogue politician and entrepreneur Clive Palmer closed the Yabulu nickel smelter in Townsville in 2016. By 2018, Australia only ranked number eleven as an export destination, receiving just 1 per cent of New Caledonian exports.

Alison Carrington sees room for more cooperation in mining services: “The technology and services part of the mining sector is an important part of our relationship. We in Australia are world leaders in this sector and have a lot to offer to New Caledonia.”

Despite this, Australia’s overall trade with the Pacific has stagnated, even as China’s has more than doubled over the past decade. In August last year, just weeks after his election as president, Thierry Santa travelled to his first Forum leaders meeting in Funafuti. “When I met prime minister Scott Morrison in Tuvalu,” says Santa, “he was very enthusiastic about us being part of PACER-Plus, the regional trade agreement between Australia, New Zealand and the independent countries of the Pacific. But we’re not really within that framework — we’d rather improve the bilateral relationship.”

At a time of geopolitical tension between China and the United States, regional interventions by Australia and France are increasingly framed by the concept of the “Indo-Pacific.”

“France is a great Indo-Pacific power,” said French president Emmanuel Macron when he visited Australia and New Caledonia in May 2018, “and it has great power in the Indo-Pacific region through its territories New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna and French Polynesia, as well as Mayotte and Reunion.” The 8000 or more French military personnel in the two oceans “project our national defence, our interests, our strategy; the region has more than three quarters of the vast maritime zone that makes us the second-largest maritime power in the world.”

Macron highlighted the strategic importance of both India and Australia, two countries where the French government is actively promoting arms sales. “Our shared priority is to build this strong Indo-Pacific axis to guarantee both our economic and security interests,” he said. “The trilateral dialogue between Australia, India and France has the possibility to play a central role in this.”

At the time, officials argued that continuing French colonial control in New Caledonia was crucial to France’s Indo-Pacific strategy. “In terms of geo-politics,” the Australian Financial Review reported, “losing control over New Caledonia’s foreign affairs and defence would undermine Macron’s strategy, of which Australia is a stated ally, to strengthen or protect France’s influence in the Indo-Pacific region — presumably as a hedge against China.”

During the visit, Macron and then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull signed a new Vision Statement on the Australia–France Relationship, extending two previous intergovernmental agreements on strategic partnership. This relationship is dominated by Australia’s $80 billion submarine technology deal with France’s Naval Group, and other ADF purchases from the arms manufacturer Thales.

After a decade of negotiation, Australia and France also signed a Mutual Logistics Support Agreement in 2018, a deal promoted as “symbolic of the strategic depth and maturity of relations between France and Australia in the field of defence.” The agreement increases intelligence sharing and allows French and Australian naval and air units to use each other’s ports, fuel and logistics in the Pacific.

Alison Carrington sees cooperation between the Australian Defence Force and the Forces Armées de la Nouvelle-Calédonie, or FANC, as a key part of the burgeoning relationship with Paris and Noumea. “Sitting here in Noumea, where the French armed forces are headquartered, this part of the relationship is a really crucial one,” she says. “For a long time, there’s been a good level of cooperation between Australian and French defence forces, preparing for and responding to humanitarian disasters in the region. But I’d say we’ve gone up from a good level to a very good level now.”

Carrington points out that Australia’s chief of the defence force made his first visit to Noumea, with his New Zealand counterpart, in January this year. She also welcomes a new ADF liaison officer, to be based in Noumea later this year. “That person will share their time between the consulate-general and the French armed forces headquarters. That will only further enhance our interoperability.”

“There’s an alignment between Australia’s ‘step-up’ engagement with the Pacific and France’s Indo-Pacific axis strategy,” says Carrington. “Both of us see ourselves committed to security in the region and meeting the security needs of the region. In that sense, France is a very important partner for Australia.”

The closeness of this relationship will be tested, however, in coming years. New Caledonia will hold a referendum on its political future on 4 October. Fearful of upsetting the global security relationship with France, Australian ministers are loath to publicly champion the “right to self-determination” for colonised peoples. But the Kanak independence movement sees status quo definitions of “security” as reinforcing France’s colonial control. The ebb and flow of neighbourly relations will continue to be affected by their call for sovereignty and independence. •

Reporting for this article was supported by a Sean Dorney Grant for Pacific Journalism through the Walkley Public Fund.