It’s no surprise that Australian thinkers, poets and bohemians visiting Paris in the early twentieth century were entranced by the city. The novelist Christina Stead called it “the capital of the modern world,” and a string of Australian writers and artists visited to sample its delights. But what should we make of the bushman back in Australia who moved around the ancient forests of Gippsland with a miniature French novel in his pocket, despite reading very little of that language?

We know about the bushman’s interest in Balzac, Flaubert and Hugo because it was recorded, no doubt with satisfaction, by Paul Maistre, the French consul in Melbourne at the time. A career diplomat, Maistre dabbled in poetry and cherished his time away from work. In this instance he was using his spare time to explore the region east of Melbourne.

Maistre was one of the figures I encountered after I moved to Australia in 2007 and started reading about the French men and women who had made l’Australie their home (in his case, for nearly twenty years). I read about the peasants who migrated from regions like Aquitaine, the wine growers, the dynasties of wool buyers from Roubaix and Tourcoing, the courtesan-cum-countess who lived on the goldfields, and the cabin boy who lived for seventeen years with an Aboriginal family on the Cape York Peninsula. I was looking for a genealogy of belonging to create a place for myself in this new country.

Some of these people, ordinary and extraordinary, went back to France; others disappeared quickly into the population, leaving only faint traces: an exotic-sounding surname, perhaps, or an intriguing family legend of sometimes dubious aristocratic origins. In all, though, the stories of these migrants never quite crossed over that illusory line that separates strangers, and the French largely remained adjuncts to Australian history.

In my new book, French Connection: Australia’s Cosmopolitan Ambitions, I try to bring the strands together: the bushman and his treasured miniature book, the wool buyers and their families, the migrants who stayed, and a cast of other Australian characters. I do this by focusing not on the French as a migrant group but rather on the idea of Frenchness as performance, a doing rather than a being.

I ask why a connection to France and French culture mattered not only to French migrants but also to colonial Australians, and how they used it in their social lives. Did reading or simply owning a French book make you look chic and worldly? A Parisian dress, sophisticated? I wanted to put my finger on that elusive je ne sais quoi. Could a French connection mean more than personal distinction in a set of settler colonies on the cusp of federation? What role, I wondered, did the French empire in the Pacific play in all this? And what did the French themselves in Australia make of it all?

What struck me most as I dug into the archives was how French culture had, by the nineteenth century, become a global culture that could exist without the French.

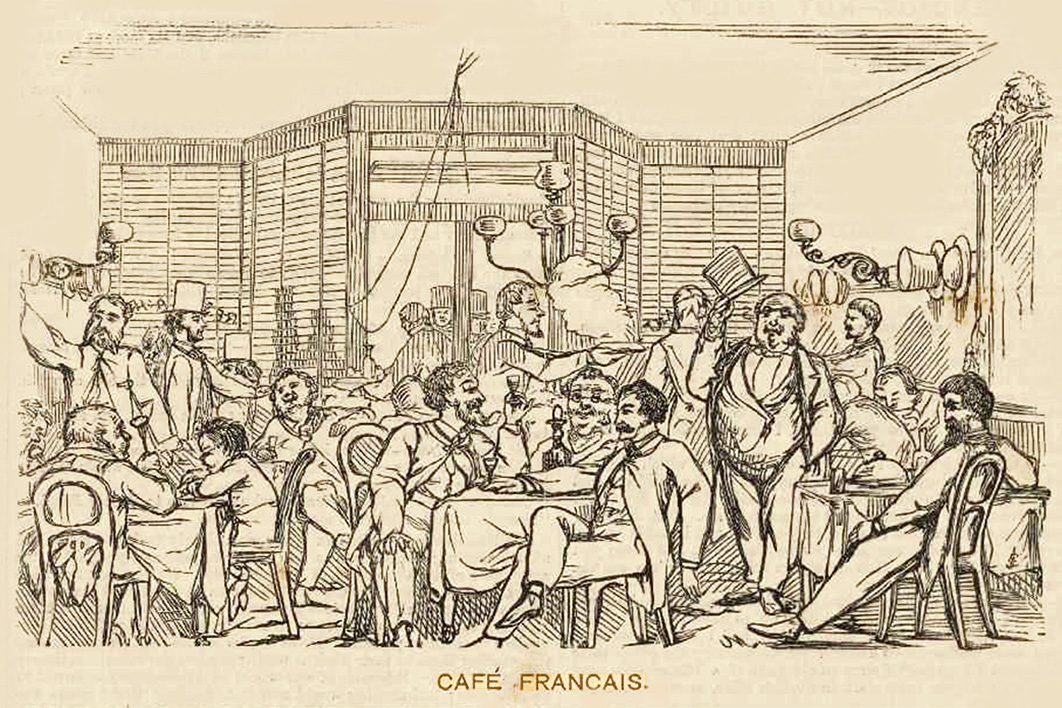

As the historian Inga Clendinnen once wrote, “particular cases” are “where the action is.” I focus on those encounters and moments of conflict where different understandings of Frenchness are most salient. And so we start with the Australian artist Norman Lindsay surreptitiously watching two female lovers at Paris’s Olympia Café. We dwell on the decade-long conflict that pitted Melbourne women of the colonial bourgeoisie against the French consul in a battle for control of the Alliance Française, and watch colonial governments trying to demonise French convicts from New Caledonia in the push for federation. And in the end, the book considers the changing nature of an attachment to France for immigrants themselves, as they gradually become Australian.

These interconnected stories are an invitation to consider how Australia has always been fashioned by international influences. I chose to focus on the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century because of the influence those years of national formation continue to have on our national psyche. The “Australian legend” — of white egalitarianism, mateship, irreverence for authority, and the rugged manliness that culminated in the bloody sacrifice at Gallipoli — has become what the historian Pierre Nora calls a lieu de mémoire, or a site of memory, an almost unshakable foundational myth. As a foreigner wanting to belong, the legend did not give me a way in, so I tried to retell the story, looking for other cultural and material ways in which Australia and Australians were connected to the world outside the British empire.

As we continue to struggle with a global pandemic, the temptation for parochial protectionism is strong. But the idea of “Fortress Australia” is nothing new, and now might be the ideal time to reflect on how cosmopolitan our history truly is, and how much we owe to strangers — even the French. •