The Labor Day long weekend at the end of August marks the end of summer in the United States, and this year it also signifies the beginning of peak campaigning for the first midterm elections of Joe Biden’s presidency. A series of speeches by political leaders in the battleground state of Pennsylvania last week highlighted the political (and maybe civil) battles ahead.

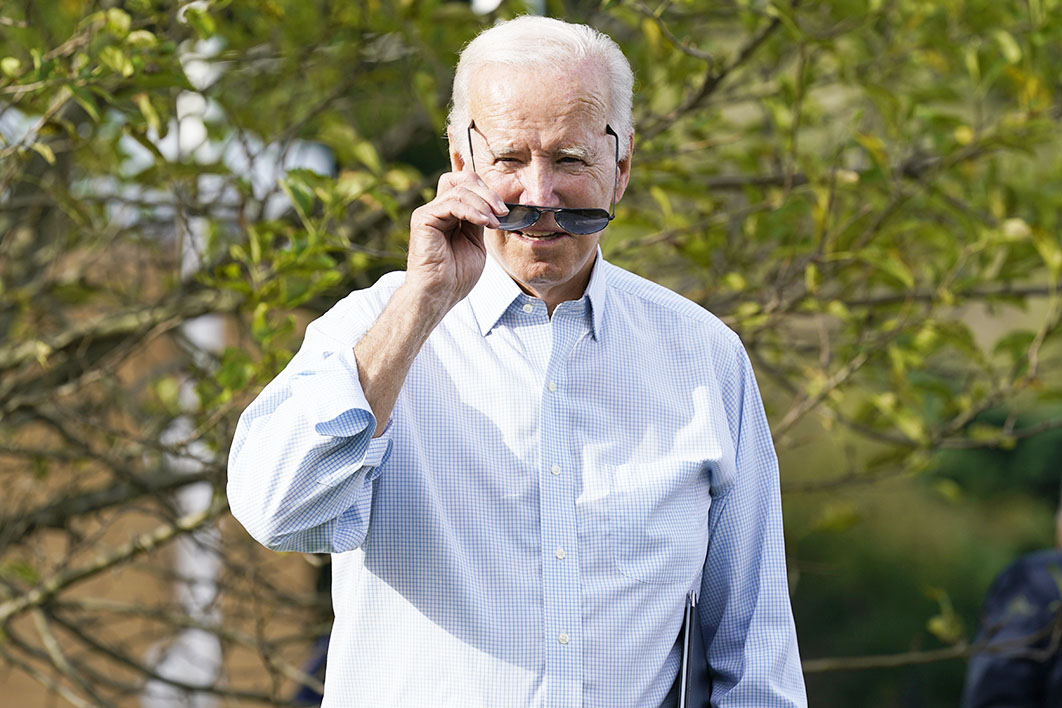

Biden’s speech in front of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall last Thursday may well come to be seen (in Biden’s words) as “one of those moments that determine the shape of everything that’s to come.” Biden castigated Trump and the Make America Great Again, or MAGA, wing of the Republican Party for pursuing an anti-democratic agenda and fomenting civil unrest, and underlined how the extremism of Trump and Trumpism threatens the very foundations of the nation.

That the current president was warning the nation of the dangers posed by the former president on the steps of the building where both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution were debated, written and signed underlined the significance of Biden’s words.

He went on to remind Americans that they are “not powerless in the face of these threats — we are not bystanders in this ongoing attack on democracy” — and concluded with a call to “Vote, vote, vote.”

Biden didn’t come lately to this theme. He says he was driven to run for the presidency again after the white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. Amid fears that the forces that drove the 6 January attack on the Capitol aren’t fading away, he recently convened private meetings with leading historians and political analysists to discuss growing dangers to American democracy.

Even as Biden’s speech was being written, Trump was urging his followers to attack the FBI and the justice department and demanding yet again that he be declared the rightful winner of the 2020 election or that the election be re-run. Trump ally, Senator Lindsey Graham, was threatening civil violence if Trump was prosecuted for illegally possessing government documents.

The key Republican responses to Biden’s speech were also delivered in Pennsylvania. House minority leader Kevin McCarthy — the man who looks to be Speaker after the midterm elections — used a speech in Scranton to align himself with Trump’s efforts to undercut federal law enforcement over the search of Mar-a-Lago. He delivered a point-by-point condemnation of Biden’s policies and, in words that presaged Biden’s later that day, accused the president of launching “an assault on our democracy” with policies that had “severely wounded America’s soul.”

Two days later, at what was billed as a rally for Republican candidates in Wilkes-Barre, Trump delivered his own explosive, aggrieved response. He called Biden “an enemy of the state” and the FBI and the justice department “vicious monsters,” escalating the attacks he has made on his social media website. Dialling up the rhetoric, he called Biden’s words at Independence Hall “the most vicious, hateful, and divisive speech ever delivered by an American president.”

It’s no coincidence that Biden and Trump converged on Pennsylvania: with several high stakes, competitive races, the state is emerging as the nation’s centre of political gravity. The outcome of the open race for governor between Democrat Josh Shapiro, the former state attorney general, and Republican Doug Mastriano, a former state senator backed by Trump, may determine the future of abortion rights and free and fair elections in a state that has a Republican-led legislature.

Meanwhile, lieutenant-governor John Fetterman, recovering from a stroke, and Trump-endorsed celebrity TV physician, Mehmet Oz, are engaged in an ugly contest over who will replace retiring Republican senator Pat Toomey. The battle has included unedifying clashes over the price of the vegetables needed for crudités and concerns that Oz has spread misinformation and spruiked unproven medical treatments.

Trump narrowly lost Pennsylvania to Hillary Clinton in 2016 (by around 50,000 votes) and to Biden in 2020 (by just over 81,000 votes) but polled well in predominantly suburban and rural counties. The question for 2022 is whether this political alignment will hold or whether moderate suburban voters and the white rural and working-class voters who once embraced Trump will now reject the candidates he backs. And if that’s the case in Pennsylvania, what of the rest of the United States?

The conventional wisdom in American politics is that the president’s party loses ground in midterm elections. Midterms are referendums on incumbents and almost no president has escaped a tough critique: in the nineteen midterm elections between 1946 and 2018, the president’s party only once improved its share of the popular vote for the House of Representatives. Only twice in the past 100 years has the president’s party gained seats in both the House and Senate.

The Democrats hold razor-thin margins in both the House and the Senate. House Democrats have a mere six-seat advantage, and Republicans are helped by partisan redistricting in Republican-controlled states and the fact that more Democrats (thirty-one) than Republicans (nineteen) are retiring. Republicans need to win only one seat to take control of the Senate, a victory that would kill any chance of Biden implementing his agenda during the second half of his term.

But political pundits are now seeing 2022 as a year in which precedents might be broken and assumptions cast aside, not just in Pennsylvania but across the nation. Democrats have a new sense of optimism about the possibility of blunting predicted Republican gains.

Just a few months ago, the discussion was about how big the “red wave” was going to be. (Confusingly, Republicans are labelled red and Democrats blue in the United States.) On 2 June the respected Cook Political Report declared that things looked ominous for the Democrats; on 30 August it concluded that Republican control of the House was no longer a foregone conclusion.

Last weekend, Race to the White House gave the Democrats a 61.34 per cent chance of retaining the Senate. FiveThirtyEight, which gives the Democrats a 68 per cent chance, attributed the surprise figure to poor candidates in battleground states. Other political analyses are more cautious, but it’s reasonable to postulate that the Democrats might gain one or more Senate seats.

It still takes a lot of optimism to believe the House will stay under Democratic control, but the twenty-to-thirty-seat gains once predicted for the Republicans have narrowed to ten to twenty. (The 270ToWin consensus forecast is here.) Under the circumstances, holding the Republicans to less than ten extra seats could be viewed by Democrats as a victory of sorts.

Several issues have brought the pollsters and the pundits to envisage what one Republican strategist described as “more like a shallow red puddle” than the red tsunami predicted earlier.

The first is that women, especially Democrats and Independents, have been fired up by the US Supreme Court’s decision to reverse the constitutional right to abortion, and subsequent state efforts to limit women’s access to abortions and reproductive healthcare. American women are engaging politically in a way that has not been seen before.

The number of women registering to vote has surged, especially in deep-red states like Kansas, Idaho and Louisiana, where abortion rights have already been severely curtailed, and in key battleground states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Ohio, where the electoral stakes for abortion rights are highest.

“In my twenty-eight years analysing elections, I’ve never seen anything like what’s happening in the past two months in American politics,” wrote political strategist and pollster Tom Bonier on Friday. “Women are registering to vote in numbers I’ve never witnessed.”

In August, Kansas — a red state that hasn’t backed a Democrat for president in nearly sixty years — voted overwhelmingly to keep abortion rights in the state constitution. An estimated 69 per cent of new voter registrations ahead of the ballot were women.

In a string of recent House special elections, Democrats have out-performed expectations. Again, abortion has been a key driver. A surge in women voters helped Democrat Pat Ryan prevail over Republican Marc Molinaro in the special election last month in New York’s 19th congressional district, a swing district in the Hudson Valley that Biden won in 2020 by just two percentage points. After the race turned into a clearcut battle over abortion rights, Ryan exceeded the vote of the Democrat in 2020 and ran 1.3 per cent ahead of Biden in 2020.

Despite the prognostications — and evidence — that abortion could be a winning issue for Democrats, all but a very few Republicans are not listening. But it’s telling that Republican candidates in critical races in states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Colorado, Arizona and North Carolina are scrubbing abortion language from campaign websites and adjusting their rhetoric on the hustings.

An election centred on the removal of a constitutional right has no precedent. And while the focus is on abortion rights, other minorities — LGBTQ and Trans groups, for example — are concerned that their hard-won rights will also be taken away by the Trump-appointed conservative majority on the US Supreme Court.

Also changing the election dynamics is Trump’s involvement in divisive primaries. He has hand-picked his acolytes for House and Senate races and for offices responsible for counting and certifying the votes in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan and Wisconsin, the states that denied him victory in 2020.

The candidates he has backed have had mixed success in often-bitter Republican primaries and beyond, which might signal that his influence on his party has waned. But the Democrats’ prospects in the Senate are undeniably enhanced by his pick of inexperienced (to put it politely) Republican candidates including Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania, J.D. Vance in Ohio, Hershel Walker in Georgia and Blake Masters in Arizona, all of whom have underperformed in polls despite Trump’s backing.

Trump’s support didn’t help Sarah Palin either; she lost the Alaska special election to replace Republican Representative Don Young, who died in March. Democrat Mary Peltola, who won under the state’s new ranked-choice voting system (which operates like Australia’s preferential system), becomes the first Alaska Native to serve in Congress. She will face re-election in November, again against Palin and Nick Begich, a more moderate Republican. It will be interesting to see if Palin’s rhetoric changes after her unexpected loss.

Trump and his allies’ aggressive midterm strategy is seen in the Republican party as a double-edged sword. Republicans don’t win if they don’t turn out the Trump voters, and the former president can boost excitement among that group, but he can also turn off moderates and independents — and Republicans can’t win with Trump voters alone. Republican candidates also fear that his capacity to dominate the political news will undermine the task of making the election all about Biden and the Democrats.

This problem for Republicans has an upside for Democrats (and America). If Trump’s role in the campaign delivers losses rather than victories then his 2024 presidential candidacy will be less likely.

More trouble for Republicans comes from a slowdown in fundraising, a strong sign of flagging electoral support. With small donors pulling back, online fundraising has slowed across much of the party. Some Republicans suspect Trump’s relentless fundraising pitches and cash hoarding has exhausted a donor base also affected by cost of living pressures. Worryingly for Republicans, Democratic contributions have meanwhile surged.

Republican Senate candidates who spent big on bruising primary campaigns are now finding that the National Republican Senatorial Campaign, or NRSC, is pulling advertising, even in critical states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Arizona. The conflict has intensified between Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell and the NRSC’s chairman, Senator Rick Scott of Florida. McConnell has argued that huge sums of money (some US$150 million so far this election cycle) have been spent on poor quality candidates; Scott has retorted that “trash talking” Republican candidates is “treasonous to the conservative cause.”

Despite his (justifiable) concerns, McConnell is investing millions of dollars from his Senate Leadership Fund to support J.D. Vance in Ohio and Oz in Pennsylvania, both of whom have been running poor campaigns. He has also pushed Trump ally Peter Thiel, who has been bankrolling MAGA candidates, to continue to fund Masters in Arizona and Vance in Ohio, but has reportedly been rebuffed.

McConnell’s preoccupation with ensuring he resumes the Senate leadership is also hindered by his increasingly bitter feud with Trump, which the former president revived after McConnell criticised the quality of Trump-backed candidates. “Mitch McConnell is not an opposition leader, he is a pawn for the Democrats to get whatever they want,” Trump said, calling for a new Republican leader in the Senate to be picked “immediately.”

Trump’s gripe is no doubt partly driven by the fact that Biden and the Democrats can lay claim to a significant list of recent legislative achievements. These include the Inflation Reduction Act, with its major climate change, healthcare and tax reforms, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the PACT Act, which expands medical benefits for veterans exposed to toxic fumes at military bases.

These bills have helped counter public perceptions of a do-nothing Congress. Biden has also used his presidential powers to tackle issues like student debt, gun control and access to abortion that would have been blocked in Congress.

At a time when American voters are worried about cost-of-living pressures and pessimistic about where the country is headed, will these achievements — along with historically low unemployment and gas prices finally going down — be enough to influence their votes in November?

Maybe, but to strengthen their argument that midterm defeats will bring dark times, Biden and the Democrats are also forcing the Republicans to play defence on issues like the rule of law and public safety (on which Trump’s vendetta against the FBI is no help). Biden has also moved to put democracy and political violence on the agenda. These are issues the polls indicate voters of both parties care about (although perhaps in different ways for different reasons) and polling shows they are beginning to affect voters’ intentions. FiveThirtyEight’s generic congressional ballot has the two parties basically even, with the Democrats leading by a little less than a point, on average, but trending up since the beginning of August.

After hitting a low of 37.5 per cent in July, Biden’s approval rating has risen by more than five percentage points on FiveThirtyEight’s presidential approval tracker. When presidential approval ratings are less that 45 per cent their party tends to lose a lot of seats in Congress. Trump, though, with an approval rating of 39.8 per cent, is even less popular than Biden.

Neither Biden nor Trump is on the ballot in November, but their influence is important. A recent Wall Street Journal poll shows that Biden would defeat Trump by six percentage points in a hypothetical rematch this month. The more Trump is on people’s minds, says a CNN analysis, the better Democrats are doing.

While the non-MAGA Republicans want to ensure that the 2022 election cycle is a referendum on Biden not Trump, it is clear that Trump will do everything possible to stay in the news cycle and thus muddy the message. He brazenly demonstrated this by delivering what David Frum called “a protracted display of narcissistic injury” in Pennsylvania. Nothing could more perfectly have amplified Biden’s message. Can Democrats now widen the new but narrow path to winning in November? •