The most common explanation for Australia’s housing woes is a lack of supply. Property values and rents have outstripped incomes for a simple reason: we haven’t built enough homes to accommodate a growing population. If we want to make housing affordable again, we must free up developers to build more.

The prevalence of this view explains the near-universal condemnation of the Coalition’s election policies. Peter Dutton’s promise to let first home buyers raid their super balances and deduct mortgage interest from their tax would have increased demand without increasing supply, pushing prices even higher. His plan to relax the tests banks must apply when they assess a purchaser’s capacity to cope with interest rate hikes would have done the same while raising financial risk.

Labor’s pledge to expand two programs that encourage home ownership can be criticised on similar grounds. One enables first-time buyers to secure a mortgage with only a 5 per cent deposit. The other facilitates “co-buying” with the government. While less inflationary than the Coalition’s offerings, both schemes would increase demand rather than expanding supply.

But Labor is building dwellings too. In its first term it established the Housing Australia Future Fund to finance 30,000 new social and affordable homes over five years. The Coalition would have scrapped the fund if it had won office and most of those urgently needed homes would never have been built. Labor’s $2 billion social housing accelerator program will provide another 4000 homes for people in urgent need of housing, and a further 10,000 affordable dwellings are promised under the National Housing Accord with the states and territories.

During the campaign, Labor also announced a $10 billion build-to-sell initiative. In a scheme harking back to the postwar decades, Canberra will provide concessional loans and grants to help the states and territories build 100,000 lower-priced dwellings for sale to first home buyers. This is a cautious, toe-in-the-water version of the Greens’ pitch to turn the federal government into a property developer. Hal Pawson from the City Futures Research Centre at UNSW describes Labor’s plan as “a bold initiative” that challenges conventional views about the limits of government involvement in housing.

Labor has also introduced tax concessions for build-to-rent projects with fifty or more apartments. To qualify, developers must provide five-year leases and offer at least one-in-ten dwellings at a significant discount. Labor claims the measure will support the construction of around 80,000 homes. The Coalition and the Greens attacked the move — the Coalition arguing it did nothing to advance the dream of home ownership, the Greens blasting it as corporate welfare. But experience overseas suggests a bigger build-to-rent sector can increase the supply of apartments while also moderating the boom–bust nature of higher density building.

Pawson’s research shows that Canada’s “mature and thriving” build-to-rent sector, for example, generates a steadier flow of apartment construction than in Australia. Here, the focus is on building units for sale, a market subject to dramatic ups and downs.

The difference lies in the financing. Funds for large build-for-sale projects are contingent on most units being pre-sold. But owner-occupiers generally prefer to see a finished product before buying, which means that developers are reliant on the willingness of investors — often from offshore — to purchase off the plan. Finance for build-to-rent projects, by contrast, is based on long-term rental returns rather than short-term gains; and this, says Pawson, brings greater immunity to market fluctuations.

Promoting build-to-rent breaks with the Australian preoccupation on home ownership as the primary goal of housing policy. It still conforms, though, to the conventional view that private investment rather than public funds should deliver the vast bulk of new homes. Since it’s more profitable for private developers to build the housing that wealthier people desire than to build the housing poorer people need, this strategy will perpetuate current inequalities: many Australians don’t have enough housing while others have too much. Australia’s tax settings contribute to the problem; by protecting housing as a store of wealth, they encourage overinvestment. This is both unfair and inefficient, as the number of spare bedrooms around the country shows.

An overwhelming focus on supply tends to push these concerns about distribution to one side. Yet they should share centre stage, because the dominant view — that a lack of housing explains Australia accelerating rents and prices — doesn’t tell the whole story.

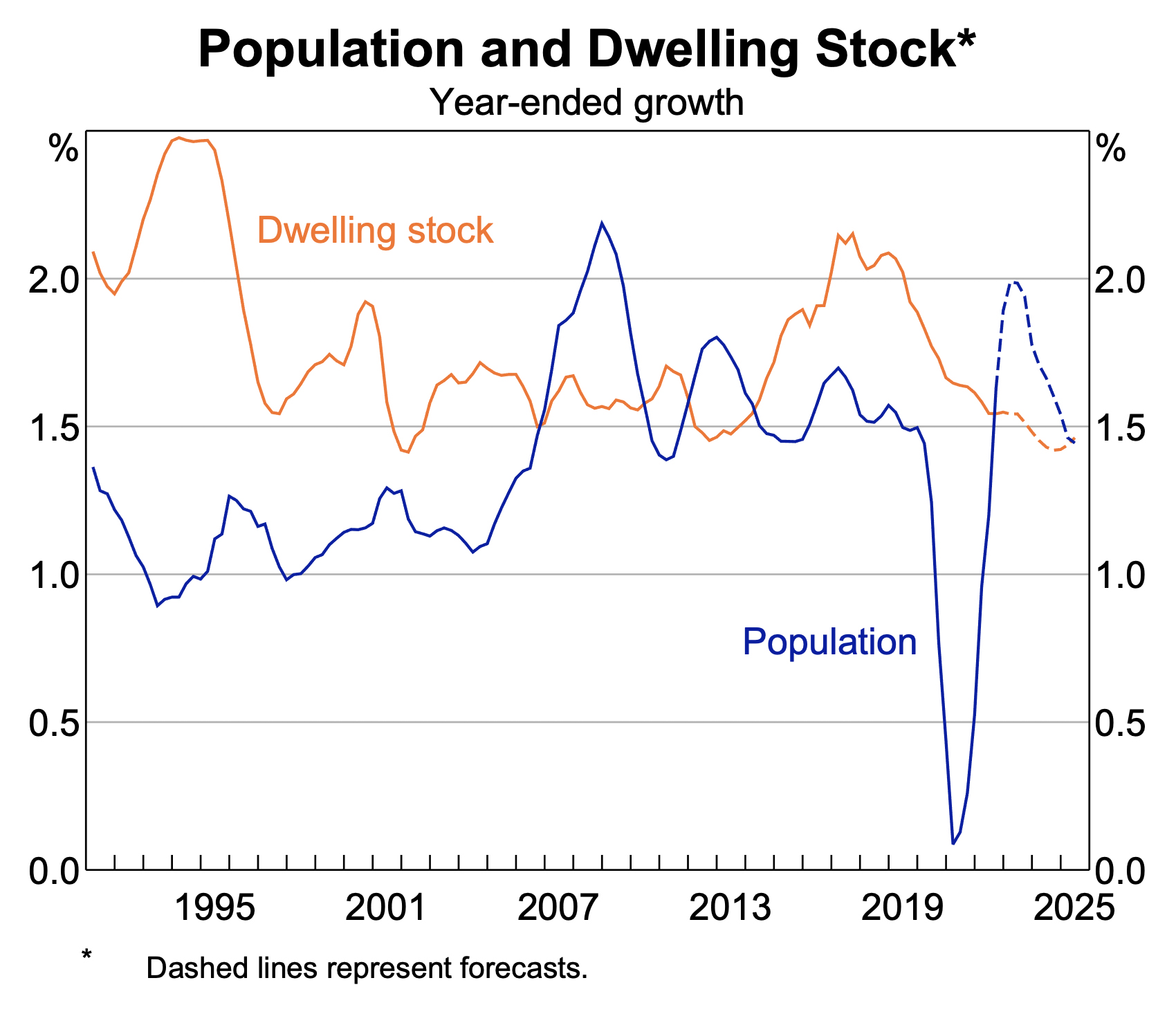

The Grattan Institute, a leading proponent of the lack-of-supply view, argues that “construction in recent years hasn’t kept up with increasing demand.” But the relationship between population growth and dwelling growth is beset by chronic volatility rather than a persistent pattern of undersupply. The peaks and troughs shown in this Reserve Bank chart (released in April 2023) suggest that business cycles, interest rates and external shocks like the Covid pandemic play a bigger role than planning rules in determining how many new homes get built each year.

To back up its lack-of-supply argument, Grattan published a league table of thirty OECD nations showing that “Australia has less housing per person than most other countries.” I’ve confirmed that’s the case in my own table, which uses the same dataset but limits the comparison to twenty countries that share with Australia a long-established market economy and democratic electoral system.

With only 420 dwellings for every 1000 inhabitants, Australia languishes at the bottom of the table together with five other nations notorious for failing housing markets and severe homelessness — England, the United States, Canada, Ireland and New Zealand. The top-ranking nations — Italy, France, Portugal, Finland and Spain — all have more than 560 dwellings per 1000 people.

It seems like an open-and-shut case: too few houses, too much unmet demand. But a closer look reveals a more complicated picture.

With an average floorspace of eighty-four square metres per person, Australia builds much larger homes than most other countries. The average home in Germany has less than fifty square metres person and in Japan it’s less than forty. If we revised the table to show the amount of living space per 1000 inhabitants, Australia would undoubtedly climb the rankings.

Other factors muddy the picture further. Spain, for example, sits near the top of the OECD table, with 563 dwellings for every 1000 people. According to the supply theory, its housing market should be relatively benign. Yet, like Australia, it is gripped by a housing crisis. Rents have risen by 80 per cent over the past decade, resulting in mass demonstrations and rent strikes that have made housing a top political concern. Tourism has been blamed for converting apartments from long-term rentals into short-stay accommodation.

Italy also appears to have plenty of housing to go around, but there, too, young adults complain of being forced to stay in the family home because they can’t find affordable rentals. Tourism, high rates of youth unemployment and a lack of dedicated student accommodation contribute to Italy’s challenges.

Meanwhile, there are many empty houses in Italian villages, something that is also true of Portugal and Japan. Declining rural populations inflate the national ratio of dwellings to population without adding to housing supply in a meaningful sense.

Demography is at play in other ways. Countries towards the top of the OECD league table generally have much older populations than countries near the bottom. In Italy, the median age is 48.4, in France 42.6 and in Spain 46.8. In Australia, meanwhile, the median age is 38.1, in New Zealand 37.9, and in the United States 38.9.

In a country with an older age profile, more people are likely to live alone or in couple-only households, which increases the number of houses needed to put roofs over everyone’s heads. Younger countries like Australia need fewer dwellings per person because more people, including families with dependent children, live in larger households.

As this scatter plot shows, median age correlates clearly, if imperfectly, with number of dwellings per head. Australia and other laggards in the OECD housing supply stakes — with their relatively youthful populations living in larger households — are clustered towards the bottom left-hand corner of the chart. Countries with higher median ages sit further to the right because they need more dwellings to accommodate the same number of inhabitants. This adds up to a plausible alternative explanation of Australia’s low ranking in the OECD housing table.

Other OECD data raises more questions about Australia’s reputation as a home-building laggard. If we compare the share of new dwellings added to existing housing stock over the past decade or so, Australia sits second from the top.

A Financial Times analysis also ranked Australia second (behind Switzerland) according to the number of new homes built per 1000 inhabitants over the past decade.

Government’s role in housing also varies greatly between countries, whether as a direct provider of homes or a facilitator through not-for-profit associations, collectives, land trusts and other non-market mechanisms.

The countries generally considered to do the best job of housing their populations, many of them in northern Europe, have more interventionist policies and a larger share of non-market homes. Countries that struggle with the cost, quality and availability of low-income housing — Australia, the United States, Italy and Spain, for example — rely more heavily on the private market.

None of this data contradicts the case for building more homes or streamlining planning rules, especially to encourage medium-rise apartment blocks in established suburbs. But it does highlight the complexity of the problem and the pitfalls of simple dwelling-to-population ratios. Australia’s housing challenge is not as simple as building more houses.

And building more houses is not so simple either. The Financial Review reports that more than 35,000 apartments and townhouses in western Sydney are “sitting unbuilt” despite having been approved by planning bodies. The blockage is not bureaucracy or “land banking” by developers but “material and construction costs, land prices, finance fees and more competition for a limited number of qualified trades.” Across greater Sydney, building has yet to commence on more than 75,000 approved homes. As Pawson’s colleague Peter Phibbs told the Sydney Morning Herald, the market, not the planning system, increasingly determines what gets built. In current business conditions, building those homes isn’t commercially viable.

This is evident in Melbourne too. About 8000 of the city’s apartments completed between 2020 and 2024 are still unsold. That means roughly one-in-six of the apartments finished over the past four years are yet to find buyers even though countless Victorians are desperate to get a foot in the door.

Richard Temlett from property advisory firm Charter Keck Cramer told the Age that recently built apartments sell for between $8000 and $10,000 per square metre but future projects would need to sell for about 50 per cent more to be profitable. New developments are unlikely until existing stock is cleared.

Long term, Labor hopes to cut the cost of construction by spending $78 million to fast-track trade skills and $54 million to encourage innovative building techniques like prefabricated housing. In the short term, lower interest rates will reduce developers’ financing costs — but they will push up property prices at the same time. And the tragic irony is that prices will need to go up, not down, to pull construction out of its current slump.

The market approach has run aground on a contradiction — housing will only become more affordable if developers build more of it, yet developers will only build more of it if housing becomes more expensive.

In the meantime, home ownership rates fall and the number of renters rises. Existing homeowners and landlords, who can borrow against their existing holdings to invest, and benefit from tax breaks, accumulate a growing share of the value of all residential property, transferring wealth from bottom to the top, with renters helping investors to pay off their loans and accumulate capital.

This trend is often seen in generational terms — as a contest between baby boomers and Gen-Y — but it is better understood as a class divide that will intensify as wealth passes down through families. Renters will beget renters and property owners will beget property owners.

What of that other element of Labor’s housing program: its decision to make social housing a federal priority again after a decade of inaction under the Coalition government? The renewed emphasis is welcome, of course, but its limits are clear. Returns from its bespoke financing mechanism, the $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund, or HAFF, seem likely to be fully committed by 2028, and by then the other one-off injections of funding from Labor’s first term will also have been expended.

A key question facing the re-elected government is how to finance a steadily growing supply of social housing through the 2030s. Recapitalising the HAFF is one option, but there are better models, including direct investment or a revolving credit fund that ploughs rental income from affordable housing back into further building. Europe-based Australian housing expert Julie Lawson argues the latter mechanism, more efficient and less complex, works well in Austria, Denmark and Finland.

Longer-term measures to make housing fairer must also include tax reform. Labor has painted itself into a political corner on negative gearing, but it has other options. As tax expert Helen Hodgson argues, reforming capital gains tax would better deal with escalating house prices. Under current rules, investors who profit from selling an asset only pay tax on half their gain. It’s the expectation of this lightly taxed windfall that makes rental losses bearable, so reducing the capital gains tax discount would defang negative gearing too. Changes to capital gains tax are not as strongly linked as negative gearing to past Labor promises and will need to be considered as part of a comprehensive tax reform package that must be a priority for the current parliament.

A shift from stamp duty to a broad-based property tax would also improve housing outcomes. First home buyers stand to gain: instead of incurring stamp duty up front, when they can least afford it, their payments would be spread over time. By making it cheaper to buy and sell, a switch to property taxes would encourage more efficient use of housing. Empty nesters in large homes, for example, would have a tax incentive to downsize, especially given that buying a smaller place would not cost an arm and a leg in stamp duty.

Switching from stamp duty to land tax is tricky and must be done at state and territory level, but the federal government could facilitate the transition. The ACT has paved the way, and the shift is backed by most economists and by the property industry.

In the final episode of his informative podcast series Housing Hostages, ABC business editor Michael Janda asks us to imagine an Australian city where house prices have risen less than incomes over the past five years and apartment prices have not gone up at all. A city, in short, where homes have become more affordable.

That city exists, Janda says, and its name is Melbourne. In March, the median price of a house in the Victorian capital was $600,000 below Sydney, and the median price for a unit was $270,000 less, making it cheaper to buy a unit in Melbourne than in either Adelaide or Hobart. Janda says Melbourne has more first home buyers entering the market than any other capital except Canberra.

Renters are generally better off too. While it’s difficult to find an affordable rental anywhere in Australia, Melbourne’s vacancy rate is equal with Canberra’s as the highest of any city. Median house rents are lower than in any other mainland capital, while unit rents are cheaper than Sydney, Brisbane and Perth.

Many factors are at work here, but Janda attributes some of the difference to state government efforts to change the way housing is used. Examples include a levy on vacant properties, a levy on short-term accommodation, and a steep increase in land tax on investor properties. Victoria has also led the way in tenancy law reform to enhance the rights of renters and increase landlords’ obligations to provide decent homes. This combination of measures has prompted some property investors to sell up or to shift from short-stay bookings to long-term leases. It’s had the same effect on the owners of holiday homes. Both actions help to make housing more affordable to buy or rent.

That’s what one state can do with some of the limited mechanisms at its disposal. Nationally, though, housing policy during Albanese’s first term was “hyperactivity without a plan,” in Hal Pawson’s words. While there were several welcome initiatives, deeper reforms — especially tax reforms — were lacking. Australia’s housing system, he says, operates in “fossilised policy architecture” dating from the 1980s and 1990s. Yet recent decades have brought immense changes to the economic and financial environment “especially the flood of money that has cascaded into real estate.”

With responsibility for housing policy scattered across different departments and levels of government, Pawson says “a fit-for-purpose overarching strategy is a fundamentally necessary foundation for progress.” That’s a reminder that Labor’s first term pledge to deliver a national housing and homelessness plan remains unfinished business. Last time, the process was deeply flawed; this time, the government needs to bring together a plan for recasting Australia’s housing system that reflects the best evidence.

With a bigger majority and strong prospects of a third term in office, Labor can be bold. Let’s hope it seizes the opportunity. •

• Mistaken figures for Belgium and Sweden in the chart titled “Dwellings Per 1000 People and Median Age” corrected on 22 May 2025.