It is easy to agree with Alexander Vindman about the shortcomings of the international relations theory that calls itself “realism.” As a way of explaining the origins of Russia’s war against Ukraine it tends to mislead rather than enlighten. But Vindman goes further, arguing it is partially responsible for Russia’s aggression.

Influenced by realist theory, he writes, American foreign policy for “Russia, Ukraine, and the entire former Soviet space” was a “failure.” His new book, The Folly of Realism, is a compact narrative of the three and a half decades since the Soviet Union’s collapse, a period that displays “the manifest failures of both realist and faux-idealist approaches.” By the latter he means the Obama administration’s “lead-from-behind multilateralism,” which “proved utterly unsuitable for a world filled with realists, let alone with dictators and tyrants.”

Vindman’s alternative is something called “neo-idealism.” It argues that “our values are our interests” and that foreign policy should be based on morality. This would enable a more coherent long-term strategy based on the promotion of democracy and the rejection of transactionalism and short-termism. While termed “idealism” it is also “more literally realistic about achieving long-term stability and securing vital American interests.” Had “neo-idealism” guided US foreign policy, Vindman suggests, we would not be in the mess we are in today.

Vindman’s is a curious book. Released in 2025, it still has the imprint of last year’s politics all over it. It was written in a moment of mistaken optimism among US Democrats, who believed that Trump would surely be defeated. Long sections read like an expression of interest for a senior foreign policy position in a Democratic administration. It is like the election never happened and Kamala Harris is president.

That would be nice, I agree. And Vindman would have been a superb appointment to a senior post to advise her. He holds a Harvard MA in Russian, Eastern Europe and Central Asian Studies, along with a Doctor of International Affairs degree from Johns Hopkins’s School of Advanced International Studies. He speaks and reads Russian and Ukrainian. And he has significant practical foreign policy experience.

Born in 1975 in a Jewish family in Ukraine, he escaped the Soviet Union in 1979 and grew up in Brighton Beach, the Russian speaking New York neighbourhood. As a soldier he served in Korea and Iraq. After receiving a Purple Heart for injuries incurred in Iraq, he became a foreign area officer, a soldier-diplomat with expertise in the former Soviet Union. He was posted to embassies in Kyiv and Moscow before a stint as Russia expert for the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff. In 2018, he became part of the National Security Council.

But his career was derailed when he testified in the impeachment inquiry against Donald Trump, earning himself the wrath of the MAGAsphere. Since retiring from the military he has made a career in think tanks and academia. He is a major public supporter of Ukraine’s war effort, and clearly hoped a Democratic victory might allow him to pursue both his career and his calling to help Ukraine.

The Folly of Realism begins with a future that never was. Ukraine would have started a new offensive against the invaders: “On the geopolitical tailwinds of a Democratic victory in the 2024 US elections, and with a successful 2025 offensive, Ukraine would be in the best position to begin a negotiation process and wind down Europe’s largest war since World War II.” Would have been. But did not.

Books take a long time to write and then publish. They can’t be expected to be up to date in a world where what you write on Thursday for an op-ed published on Saturday might be overtaken by events by the time readers set their eyes upon it. The Democrats lost the election in early November 2024; this book was released in February 2025. Some last-minute editorial interventions could have saved it from instant ageing. Instead, a somewhat deflated afterword was appended while the triumphalist opening stayed.

Trump 2.0 “signals a deliberate dismantling of the liberal, rules-based order America once upheld,” the afterword sombrely observes. “What remains is an opportunistic, unrestrained form of ‘realism’ that bears little resemblance to the tempered pragmatism of the past — a new policy that abandons allies, disregards shared values, and undermines partnerships painstakingly built over decades.” Other powers will now fill the vacuum, with terrible results: “Russia and China, in particular, stand ready to reshape the world in their own image: a world where power is absolute, dissent is crushed, and borders are redrawn at the whims of the strong.”

An American patriot, Vindman still sees his own country as the only possible light in a dark world. “A hostile order dominated by autocratic regimes will rise in place of the one America leaves behind. Allies who relied on American support will be forced to fortify themselves against an onslaught of new threats.”

Interestingly, however, he does see some hope in the potential of lesser powers. They might combine forces to withstand the dictatorial and imperialist onslaught. “A coalition of the willing may emerge among European states,” he writes, “doubling down on their support for Ukraine’s war effort.” By the second half of 2025, we do see such a coalition developing — and it is beginning to encompass much more than Europe. Australia is part of that game, as are Japan and other democracies. Alliances might now form, indeed, “without US leadership and perhaps even without its participation.”

This analysis, like much of the rest of the book, is insightful and to the point. Vindman’s narrative of how we got here, and his final assessment, are among the most useful summaries available. The book thus deserves a wide readership, even if its suggestion that we turn from realism and towards something called “idealism” isn’t entirely convincing.

The term might work well in academia, where scholars need to position themselves with clearly recognisable labels: realists and idealists, liberals and constructivists, totalitarianists and revisionists, political scientists and historians. That way, nobody gets confused, departmental boundaries can be drawn with ease, exams set with more precision, and grant applications evaluated by the right kind of expert.

Politically, though, the term idealism is self-defeating. Who wants to be led by a bunch of idealists, after all? That, in effect, was part of the genius of the school that called itself the “realists”: it made them seem more reasonable than the soft-headed ideologues down the corridor.

The problem, however, is the lack of realism within “realism”: its theoretical, empirical, and strategic poverty. Its “unacknowledged gigantism” means it barely ever thinks of smaller powers. The mainstream brand of realism nearly always proceeds from the perspective of the “great powers” — the ones that can supposedly “do as they will.” They are the subjects of international relations, the actors, the initiators. Smaller powers are the victims who “suffer as they must,” the mere objects of international relations rather than subjects of global history. Smaller powers can only act tactically within the field of power drawn up by the “greats.”

In reality, of course, this is far from true. Small and middle powers act strategically all the time. And sometimes they play the “great” as well as anybody. Just look at the history of the cold war: again and again, the grand strategies of the two superpowers ran upon the reef of smaller powers manipulating them for their own ends.

And the power of smaller players is quite possibly even more pronounced today than in the past three and a half decades. With the end of the “age of transformation” — the period between the end of the cold war and the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine — we have entered an “age of strategic chaos.” In this new reality, multiple centres of power jostle for position, increasing risk and insecurity. But this more complex world also enhances the ability for effective action from smaller players.

Any realist (or indeed realistic) theory of international relations would have to account for this reality. Political scientists are starting to recognise this fact, and it is probably no accident that Russian scholars are particularly active in this field of theory building.

The problem with the mainstream approach to Russia after 1991 was an inability to properly understand it as a middling power with a great-power complex. Policymakers switched back and forth between treating it as inconsequential (“a gas station masquerading as a country”) and buying in to its great power aspirations. The impoverished theory of international relations that dominated foreign policy thinking in many places gave only two options: Russia was either a great power or it was nothing. The result was a kind of international politics of entitlement, where Russia lobbied for the status it supposedly deserved and the rest of the world played along, sometimes resisting, sometimes accommodating such demands.

Note that Russia, a middling power after 1991, had significant agency here. Russian elites, and in many ways Russians more generally, always saw Russia among the greats who should be allowed to do as they please. Americans and Europeans knew that this was no longer true, but still accepted the claim repeatedly.

As Vindman documents in some detail, the result was a succession of cave-ins to a Russia that became more and more emboldened in the process. When the question arose of how to deal with the proliferation of states with nuclear weapons after Soviet Union split into fifteen states, the default was to monopolise them in Russia rather than allowing Ukraine, Belarus or Kazakhstan to become nuclear nations. When Russia objected in 2008 to Ukraine and Georgia becoming members of NATO, they were left out to dry. When Russia broke international law, no consequences followed, inadvertently demonstrating that it could successfully claim the status of a great power — one that does as it pleases. The poverty of the theory led to a lack of political imagination. The consequences for Ukraine were catastrophic.

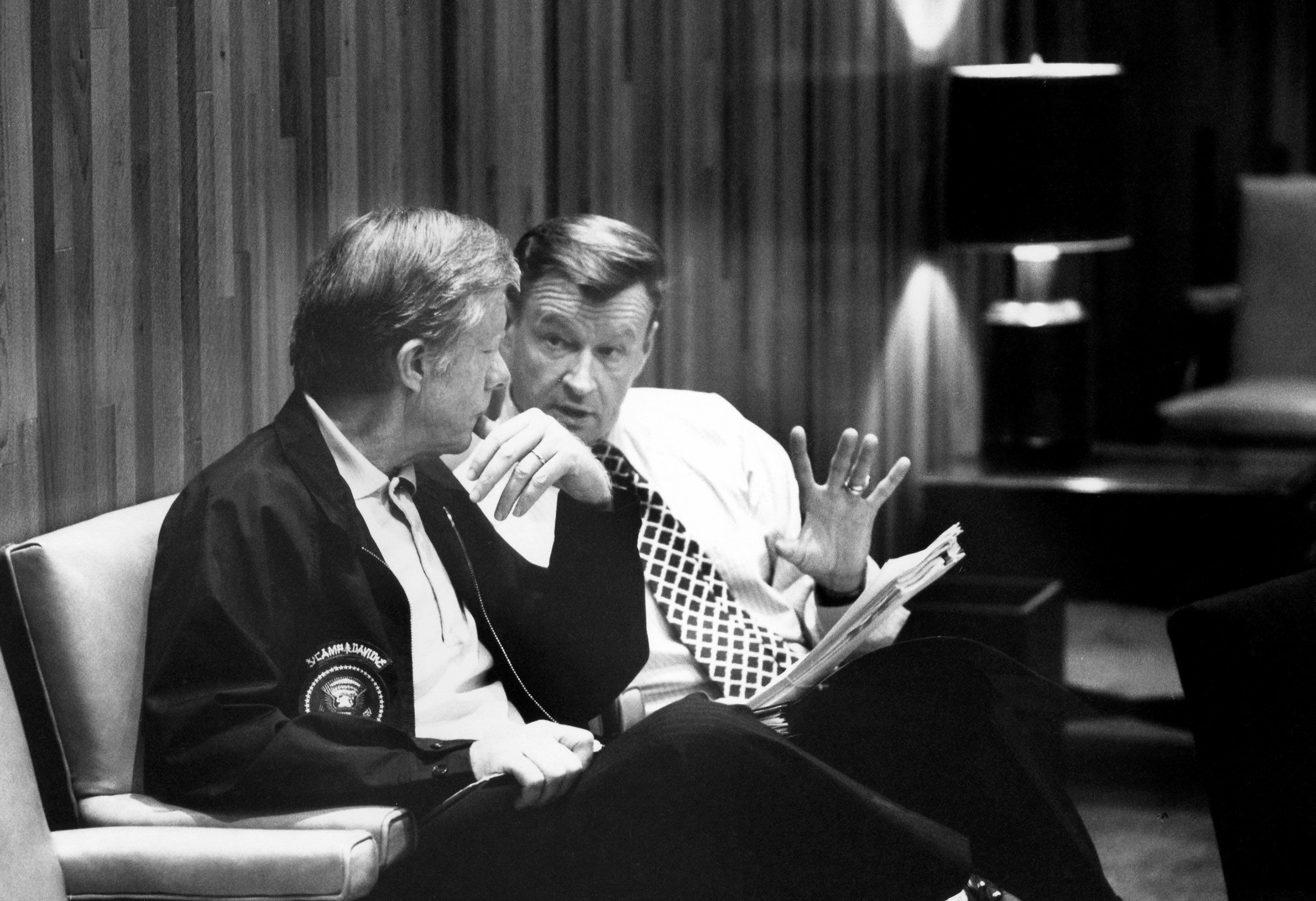

What we need, then, is a realism that thinks not from the perspective of great powers but takes into account the agency of middling and smaller nations. It might be odd to think about such a theory through the life and work of Zbigniew Brzezinski (1928–2017), usually thought of as a classical “realist” and often mentioned in one breath with his friend and rival, Henry Kissinger. As president Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, he served one of the two cold war superpowers and as a result worked on great-power strategy. But he was also the scion of a distinguished Polish family and the son of a Polish diplomat. As such, he had grown up with middle-power strategy firmly embedded in his thought.

Brzezinski’s strategy towards the Soviet Union was based on the assumption that the smaller powers in the Soviet orbit — the Poles, the Latvians, the Lithuanians, the Estonians, the Romanians, the Czech, the Slovak, the Bulgarians or Hungarians — had their own agency even under communism. His underlying “theory” of international relations, then, had a distinctive small-power flair, although Brzezinski hardly ever did what today is the most prestigious of the “IR” specialties: pure theorising. His theories remained implicit in both his analyses and his strategic vision.

The exception was the theory of “totalitarianism.” Here, Brzezinski made an early name for himself when, as a young scholar, he published Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy, co-authored with the established Carl Friedrich. The timing could not have been worse, as Edward Luce writes in his fine new biography, Zbig. Brzezinski’s job in this collaboration was to cover the Soviet example, but he only travelled to the Soviet Union after the book was written and had thus no first-hand experience of that society. Most scholars do their research trips before rather than after they publish their findings, but Brzezinski was in a rush.

To make things worse, Totalitarian Dictatorship appeared in 1956, three years after Stalin’s death and in the year his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, stunned the world with his “secret speech” about Stalin’s crimes. The Soviet Union was quite plainly no longer totalitarian and the theory of “totalitarianism” had become a historical artifact just at the time when it was finally systematically thought through.

The book’s timing meant it was not only useless for understanding the Soviet enemy during the later stages of the cold war but also historically naive about the system it tried to describe, Stalinism. A whole school of historical research, the “revisionist” social historians of the 1970s and 1980s, had a field day debunking the caricatured vision of the Soviet social formation of the 1930s and 1940s offered by Friedrich and Brzezinski.

Brzezinski reciprocated. He absolutely loathed the “revisionists,” whoever they might be: most likely Stalin acolytes and/or Moscow appeasers. “Right through the 1980s,” Luce writes, channelling Brzezinski, “the ‘revisionist’ school of US Sovietology continued to downplay Stalin’s crimes and argue that his brutal path to industrialisation had been necessary. The most prominent revisionist was Jerry Hough, a political science professor at Duke University, who insisted that Stalin had killed only ten thousand people.”

That’s quite a caricature. Yes, there were scholars who argued that, in effect, Stalin was “really necessary.” But there was an equally strong group of “revisionists” who thought Stalin was some kind of aberration and advocated for recovering alternative types of Bolshevism. And while Hough was off the mark with his low-ball estimates of Stalin’s victims, at least his data were based on available demographic statistics rather than wild estimates.

It is indeed difficult to say how many people “Stalin killed” (he never pulled the trigger). But estimates that his policies had tens of millions of victims are exceedingly high. Luce would know that if he had taken account of the scholarship that emerged after the Soviet archives opened in 1991. Just under 0.8 million executions are archivally documented for the years between 1930 and 1953. Perhaps nineteen million people passed through labour camps and colonies during the Stalin years, and at least 1.6 million of them died in custody. If we add people who died shortly after release (between 20 and 40 per cent were freed every year) the number of camp-related deaths probably rises to about six million. Adding in “excess deaths” — fatalities caused directly or indirectly by state policies — increases the numbers further. Between the censuses of 1926 and 1939, an estimated ten million people died who under normal circumstances might have lived. The postwar famine of 1946–47 claimed another 1.5 million victims. And during the war with Germany in 1941–45, some twenty-seven million people departed this world prematurely.

In other words, only if we add the war-related fatalities and chalk them up entirely to Stalin’s policies (rather than the Germans’ genocidal war making) do we get to the “tens of millions” Luce declares “the true figure.”

Given Brzezinski’s status as the bête noir of the revisionists and given his own dislike of his critics, it is rather amusing to learn that he shared their judgement of Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy. He quietly agreed that his early book was off the mark. He barely ever cited it. He didn’t promote it. He didn’t participate in the revisions to the second edition of 1965. Although his name still appeared on the title, the new preface was written by Friedrich alone, who made it clear that “Zbigniew Brzezinski could not participate” in the rewriting of what had now become a classic. Instead, between handing in the final revisions in 1956 and the publication of the book later that year, Zbig had done what many a “revisionist” had done before him: he had gone to the Soviet Union to see for himself.

What he found there, and in subsequent trips to other parts of the Soviet bloc, was “a lot messier” than the theory of totalitarianism implied. He saw a society in decline rather than on the path to overtake the United States. And he found the kind of complexity in the internal workings of the Soviet bloc which should have delighted any revisionist.

“Though Brzezinski never put it quite so starkly,” writes Luce, “his USSR tour fuelled doubts about the watertightness of his and Friedrich’s totalitarian theory.” A shrewd operator in the power games of academia, however, Brzezinski kept mum about his change of heart. The book continued to be valuable to his academic career, after all, because those who disagreed with it continued to cite it. “Though he no longer agreed with the book’s thesis, Brzezinski basked in his newfound recognition,” observes Luce. This recognition took him from Harvard to Columbia and on to Washington.

Brzezinski’s theory of totalitarianism, then, had no impact on his strategic thought vis-à-vis the Soviet Union or later Russia. Instead, a notion emerged very much at the opposite end of the theoretical spectrum: that the Soviet Union itself was decaying and the “Soviet bloc” was made up of many independent actors with their own social, political, and historical dynamics that often didn’t coincide with those of Moscow. The world he described in his The Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict of 1960 (revised in 1967) resembled for the international realm the notion of “institutional pluralism” the revisionists developed at the same time for the domestic political system of the Soviet Union.

Just as the regional Soviet functionaries described in Hough’s influential revisionist work of 1969 were men with their own power and agenda, so were the leaders of the “satellites” in Eastern Europe. Neither group was just a cog in the Soviet wheel. And East European societies, to Brzezinski, had their own internal dynamics, just as different groups in “Soviet society” had in the works of the social historians who became known, like their political science comrades, as revisionists.

The revisionists hated the theory of totalitarianism. Or maybe they actually secretly loved it, in particular the six-point model promoted by Friedrich and Brzezinski. Because it was so banal. And so wrong. Whole graduate seminars could be structured around the six points, dismantling them one after the other armed with no more than a basic acquaintance with primary sources. This could then be followed up with a warning to budding Russia specialists about the dangerous consequences of such mistaken theories in the foreign policy establishment of Washington.

Except, of course, that one of the most established of establishment figures, Brzezinski, operated with something quite close to a revisionist vision of the Soviet empire, seeing it as a complex formation of competing interests in which smaller players had significant power to shape events. This vision informed not only the academic field of “comparative communism,” which he helped invent. It also shaped his grand strategy.

That strategy was focused on using centrifugal forces in the communist world to defeat the Soviet Union. In Asia, this meant propping up China as a counterweight in the international socialist and revolutionary world; hence the normalisation of relations with the rising Asian power. In Europe, it meant supporting the interests of the satellites, in particular Poland, and trying to avoid yet another Soviet crackdown that could set such independence back by years or decades. And in dealing with the Soviet Union, it meant flexibility: encouraging the dissident movement to increase domestic pressure on the regime; engaging the Soviet government productively where possible (via the SALT II weapons-control talks); and supporting anti-Soviet forces militarily, such as in Afghanistan from 1979.

This was not just hard-headed “realism” devoid of any ideals. It was driven by the thoroughly idealist, even utopian, goal of freeing Eastern Europe from Moscow’s grip. It also aimed for “world community,” a global order dominated and directed by the United States.

Not unlike the “neo-idealism” Vindman advocates, Brzezinski’s realism was confident in the powers of democracy and the attractions of liberalism and market economies. “What I valued most about Zbig was that he taught me to think deeply about the nature and purpose of American leadership,” noted his student and later colleague, Madeleine Albright. Maybe not incidentally, she did so during a speech at the School of Advanced International Studies, which links Brzezinski (who held a chair there) and Vindman (who earned his doctorate there many years later).

“In emphasising both interests and values, Brzezinski reflected his view that American foreign policy must be shaped not solely on the basis of what we are against but also what we are for,” Albright added. This was realism with small and medium powers left in. It was not great power realism where smaller players are either pawns or victims. What they did and did not do mattered.

Brzezinski’s interests in smaller players continued after the breakdown of the Soviet Union in 1991. He worried earlier than most that Russia might harbour neo-imperialist ambitions, a view Luce attributes to his Polish background. “Dread of Russia was a non-optional piece of that Polish identity,” he writes. “Even before the Berlin Wall had fallen, Brzezinski was issuing jeremiads about Russia’s desired revenge on history.” Luce quotes Brzezinski — “We’ll probably see a turn toward some highly nationalistic form of dictatorship” — and notes that he pinpointed Ukraine as the centre of a future conflict.

The quotation that begins Vindman’s book is a case in point: “Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire, but with Ukraine suborned and then subordinated, Russia automatically becomes and empire.” It comes from a 1994 Foreign Affairs article in which Brzezinski criticised the US administration’s “premature partnership” with Russia. The strategic goal of American foreign policy, he wrote, had moved from “containment of Soviet expansion” to “a partnership with a democratic Russia.” This vision was “deliberately optimistic” because the “near-term prospects for a stable Russian democracy” were “not very promising.” It also ignored concerns “by states like Ukraine or Georgia.” And the two were linked: one of the reasons for the poor prospects for Russian democracy was lingering imperialism, which in turn threatened Russia’s neighbours: “Russia can be either an empire or a democracy, but it cannot be both… Regrettably, the imperial impulse remains strong and even appears to be strengthening.”

Brzezinski advocated for a policy that would have given Ukraine greater agency in the power tussle in the Europe–Asia region. The best way to hem in Russia — an antidemocratic force in Europe and hence to be opposed — was to help Ukraine become an independent buffer state:

The central goal of a realistic and long-term strategy should be the consolidation of geopolitical pluralism within the former Soviet Union… The basic premise of this alternative strategy is that geopolitical pluralism will foster the best context for the emergence of a Russia that, democratic or not, is encouraged to be a good neighbour to states with which it can cooperate in a common economic space but which it will not seek or be able, politically and militarily, to dominate… It would call for a more balanced distribution of financial aid to Russia and to the non-Russian states, the abandonment of the single-minded elevation of the question of nuclear arms to the status of litmus test for American–Ukrainian relations, and an even-handed treatment of Moscow and Kiev.

His nightmare scenario was what has more or less come to pass: an “anti-hegemonic coalition” of a fascist Russia, an “autocratic China” and a “resentful Iran.” As Luce writes, Brzezinski’s “prescience” in the 1990s and early 2000s was “uncanny” in this respect.

His proposed strategy evolved from what he had advocated for dealing with the Soviet Union: empower Russia’s neighbours and treat them as independent actors, not as necessary and eternal parts of Russia’s “sphere of interest”; oppose Russia where necessary but try to integrate it into Europe as much as possible in order to avoid pushing it towards China and Iran. His preferred solution for Ukraine was the “Finland option”: an independent and neutral state as a buffer between Russia and Europe. He thought this was more likely to be acceptable to Russia than NATO membership, which he therefore opposed.

Like his earlier strategy, this one was based on realism with lesser powers left in: a theory of international relations where smaller states not only have agency but also a right to independent existence. Juxtaposing such a position to “idealism” (“we follow our values”) or “realism” (“the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”) makes little sense.

The two alternatives to Brzezinski’s strategy were a sphere-of-interest approach in which, on the basis of deeply misunderstood histories and misleading historical narratives, Ukraine was assigned to Moscow; or further NATO enlargement. All three would have been viable strategies. Brzezinski’s approach would still have meant massive support to make Ukraine strong enough to stand up to Russia. And it is far from certain that it would have avoided war: it is worth remembering that Finland had to fight a bloody civil war (with Russian participation) and then two interstate wars with the Soviet Union before it was left in peace. But Ukraine would have been in a strong position to beat back the Russian assault and then truly follow the Finnish model.

Integration into NATO, by contrast, would almost certainly have deterred Russia from attacking Ukraine. But it would have angered Vladimir Putin and quite possibly pushed him towards the China–Iran axis Brzezinski thought was the worst-case scenario. An unambiguous declaration by NATO and the European Union that they accepted Russian imperialist claims to Ukraine, finally, might have prevented war but would almost certainly have ended democracy in Ukraine.

Instead, as Vindman reminds us, what Ukraine got was a confused mix of all three approaches: pressure to give up its atomic weapons, which were handed over to Russia in exchange of meaningless security “assurances” (not “guarantees”) in the Budapest Memorandum of 1994; friendly words from NATO and the EU in 2008 and after, which angered Moscow but did not amount to much in practice; and insufficient military support ever since for fear of “provoking” Russia. This was neither realism nor idealism. It was the very opposite of a strategy. It was born of the poverty of realism as practised by its main contenders. Unlike Brzezinski, they found it hard to put themselves in the shoes of middling and smaller states. We still live with the consequences of this “folly.” •

The Folly of Realism: How the West Deceived Itself About Russia and Betrayed Ukraine

By Alexander Vindman | Public Affairs | $49.99 | 304 pages

Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet

By Edward Luce | Avid Reader | $61.25 | 545 pages

Review updated 13 August to correct the US publication date of The Folly of Realism.