The movement for civil and human rights chronicled by historian Benjamin Nathans in his Pulitzer Prize–winning book, To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause, was an important moment in the long and diverse history of dissent in the Soviet Union. Concentrated in Moscow, its links to a worldwide wave of human rights advocacy during the 1970s gave it a profile denied to most other Soviet-era dissenters.

Dissident activity had begun in the years after the Russian revolution when the Soviet system was taking shape around the Marxist-Leninist “scientific worldview,” which purported to explain the past while guiding action in the present with a view to the future. Deeply ideological, the regime could not tolerate alternative interpretations of the political, economic and social world. Dissenting views were false and politically harmful by definition, and had to be suppressed. But they were never eliminated.

During the civil war after the revolutions of 1917, the Bolsheviks persecuted, sidelined and eventually eliminated alternative political parties. They never altogether outlawed religion, but its organised forms were seriously circumscribed. Then, beginning in the late 1920s, Stalin’s regime went after anybody suspected of harbouring oppositional ideas within or outside the Communist Party. But although political groups were pulverised by terror in the 1930s, their ideas continued to circulate by word of mouth and sometimes in written form, even during periods when unofficial political activity was all but impossible.

Religious worldviews, from Islam and a wide variety of Christianities to Animism and Buddhism, persisted in inspiring large sections of the population. Various nationalisms were officially endorsed only if they were “socialist in content” (though they often turned out to be anything but, and had to be condemned as “bourgeois” and repressed). The remnants of the Russian liberal tradition were reinforced by a growing knowledge of democratic practices in the outside world after the Soviet Union began to expand westward again from 1939. Anarchism and other alternative forms of revolutionary politics continued to be remembered, and the Marxist-Leninist tradition itself provided inspiration to many, often-young people confronted by the contrast between reality and the writings and the ideals embodied in the Soviet Union’s own sacred texts.

As the Soviet Union gobbled up parts of Poland and Romania and the three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in 1939–40, it effectively imported a new crop of political opponents, both individuals and organised groups. Again, it used terror to subdue dissent. Mass shootings, the favourite tool of 1937–38, were used in Poland in 1940 and at the beginning of the war with Germany in 1941, though less frequently thereafter.

Once the war was won, a new reluctance to use lethal violence found its expression in the temporary abolition of the death penalty. Mass repression in the newly annexed regions now relied more on prisons, camps and deportations. Far from being eliminated, however, the dissent was only displaced into the Soviet hinterland, dotted as it was by gulag camps and special settlements. In this archipelago of detention, people with a wide variety of worldviews could meet in a way difficult to imagine in Soviet society more broadly.

In the old Soviet territories, meanwhile, the political police arrested group after group of young Leninists who had formed small opposition groups in universities and high schools, along with veterans returning from the war with news of democracy and the good life outside the borders of Stalin’s barracks socialism.

This landscape of political pluralism behind a facade of ideological unity was transformed after Stalin’s death in 1953: the gulag, while never dismantled, was significantly reduced in size and its practices reformed; censorship was a little less stringent at times and Stalinism subjected to a highly qualified critique, although the extent of liberalisation under Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, is often overstated; a mass housing program gave more people access to private apartments, which eased conversations among networks of friends and family; and, crucially, mass terror was replaced by what the newly formed Committee for State Security, or KGB, called “prophylaxis,” an attempt at preventive policing rather than crude repression. The result was a series of protests and disturbances and the emergence of new underground groups inspired by what the authorities saw as dangerous ideas.

Several forces interacted in this new world of political dissent. One emanated from the western borderlands — Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia — and their longer history of national resistance to Soviet domination; many of those deported or arrested under Stalin would return in the later 1950s, reinvigorating political opposition movements in the Soviet Union’s wild west. A second dissident force was the Baptists, a religious community of long standing in the Russian heartland reinforced since the second world war by their Estonian brethren.

Third were Jews wishing to explore their identity after the trauma of the Holocaust but regarded, with the foundation of the state of Israel, as less likely to be loyal to the Soviet homeland. A growing group of Jews thus began to lobby for emigration to Israel, the ultimate insult to a regime that claimed to have built the best and fairest society on earth. The government accused them of “Zionism,” one of the cursed “bourgeois nationalisms” the Soviet Union could never get rid of. Those who had their application for exit permits refused became known as “refuseniks,” a new type of Soviet dissident.

But perhaps the biggest political movement of the post-Stalin years was made up of Crimean Tatars. Deported from their homeland by Stalin, they fought, unsuccessfully until 1989, for the right to return. Both the Crimean Tatar and the Jewish movements maintained networks across the wide geographical spaces of the Soviet Union.

Finally, there were Moscow-based intellectuals who would become famous as “the dissidents.” The latter came in three basic variants: Russian nationalist or Slavophile dissidents like the later Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (although he didn’t live in Moscow); neo-Leninists in the tradition of the anti-Stalinist youth groups of the final years of Stalinism, who would have an afterlife in the second generation of socialist dissidents in the 1970s; and “rights-defenders,” who tried to get the Soviet regime to adhere to its own laws — an evidently hopeless cause. It is this latter group Benjamin Nathans deals with in To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause, a remarkable book destined to remain the standard work on the topic for the foreseeable future.

The “rights-defenders” were relatively late, quite short-lived and localised contributors to political pluralism in the Soviet Union. Having emerged in 1960s Moscow, writes Nathans, they were “all but crushed by the KGB in the early 1980s.” The national movements on the Soviet Union’s western border, the networks of Baptists, “Zionists” and “refuseniks” and the organised Crimean Tatars had much deeper histories, would survive much longer, were networked well beyond Moscow, and were also significantly larger.

The Crimean Tatars had pioneered many of the techniques the rights-defenders would later optimise: newsletters published in typescript form and distributed through networks of typewriter owners who would not just read them but also type up multiple carbon copies for further distribution. This decentralised technique soon came to be known, famously, as samizdat (self-publishing). Another part of the dissident repertoire was collective letters signed by multiple authors and directed to the authorities — also an invention of the Crimean Tatar movement. The first dissidents who had made contact with the fledgling Amnesty International — later a celebrated avenue of work for rights-defenders — were Baptists, who also have the distinction of having in 1961 formed the first known “initiative group” that used samizdat for political rather than literary ends. Crimean Tatars had also formed such groups by 1966.

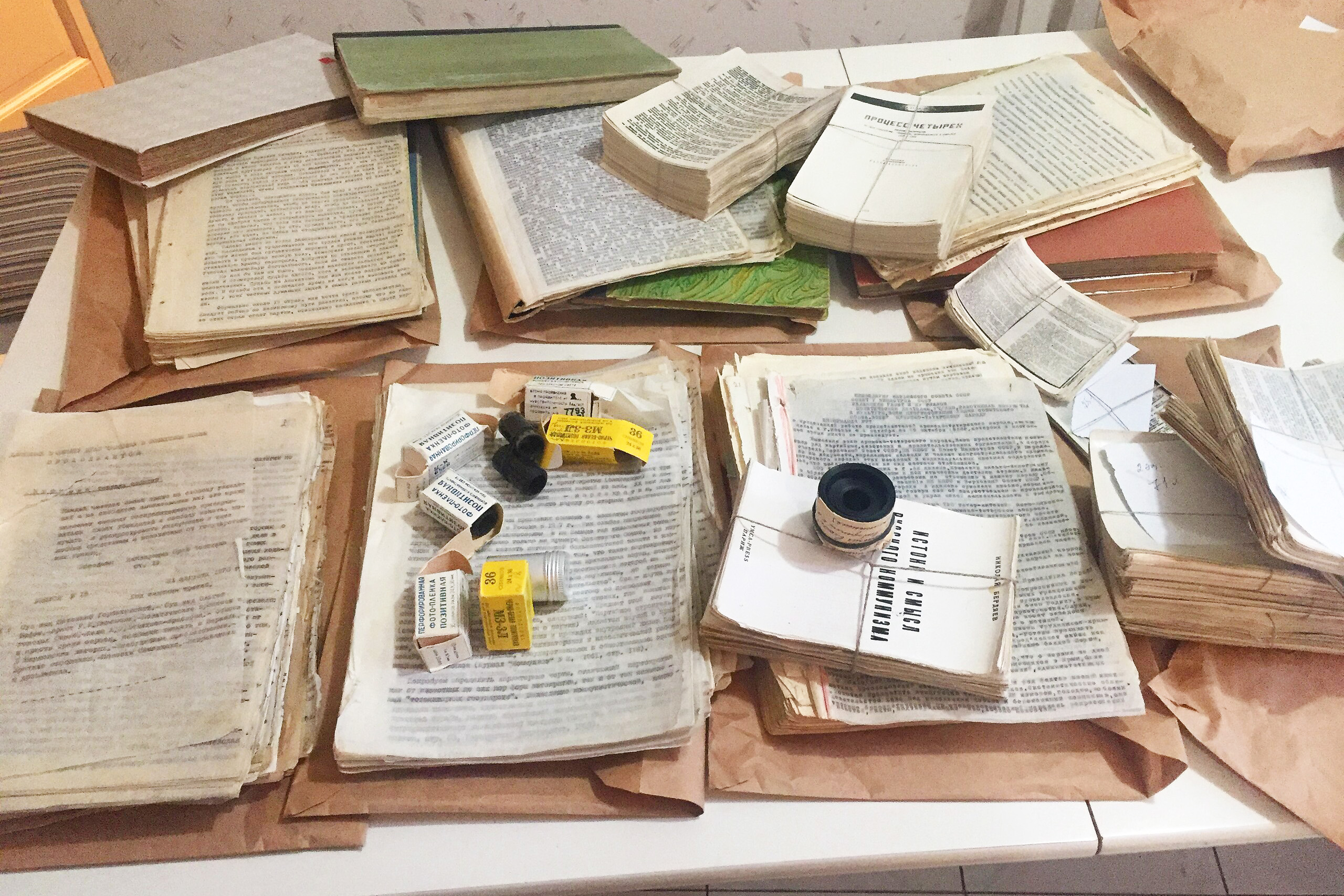

Russian samizdat copies and rolls of photo negatives. Nkrita/Wikimedia Commons

The Moscow dissidents followed these predecessors in May 1969 with the formation of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Civil Rights — “the first civil rights organisation in the socialist world,” as Nathan stresses. One of its founding members was Mustafa Dzhemilev, an early Crimean Tatar activist and later the first chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People (1991–2013). He had formed the Union of Young Crimean Tatars in 1961 and had ample experience with Crimean Tatar “initiative groups,” which served as models for this new organisation of Moscow intellectuals.

Other key members included Peter Yakir (son of the civil war military hero and Soviet military reformer Iona, who had been executed under Stalin) and fellow gulag survivor Victor Krasin, like most of the other fifteen members both Moscovites. Only one member was resident in Leningrad (Vladimir Borisov) and two came from Ukraine (Genrikh Altunian and Leonid Pliushch).

The rights-defenders would quote the Soviet constitution repeatedly in their struggle with the authorities in the 1960s and 1970s. But the practice of citing this “most democratic” basic law to further one’s own non-Soviet political agenda was as old as the constitution itself. During the campaign promoting the new constitution in 1936, religious communities welcomed the article that stated:

In order to ensure to citizens freedom of conscience, the church in the USSR is separated from the state, and the school from the church. Freedom of religious worship and freedom of anti-religious propaganda is recognised for all citizens.

Believers in Ukraine passed resolutions referencing this article, and in Kazakhstan locals took it upon themselves to open new mosques in response. More dubiously from a legal standpoint, deported peasants cited the constitution as giving them a right to return home and “make short work… of those activists who… deported us.”

Nor were the rights-defenders a particularly large group. While a total of perhaps 1000 people signed letters penned by the Moscow-based dissidents, the Lithuanian Catholic movement managed to assemble 17,054 signatures for a 1972 petition protesting the arrest of priests, and Crimean Tatars had managed an equally astonishing 120,000 in 1966. Between the late 1950s and 1968, in fact, the total number of signatures on Tatar appeals to the authorities reached three million. Such numbers, writes Nathans, “stunned dissidents in Moscow.” One of them reflected wistfully that “we never managed to gather more than three or four hundred signatures” on any given letter.

Why focus, then, on such a relatively small group of Moscow-based intellectuals rather than the wider landscape of dissent? Nathans gives several compelling reasons for his deep dive into the small world of rights-defenders.

For one, the Moscow dissidents had the time, energy and resources to bring order into what he calls the “dissident repertoire.” Living relatively comfortably as members of the Soviet intellectual elite, they developed a language of civil rights and then, inspired by the developing international discourse, of human rights. This new language spread to other groups, as did the dissident repertoire they had systematised rather than invented: the use of collective letters, silent protests, “initiative groups” and samizdat.

Moreover, they used these techniques not just to further their own cause as the Crimean Tatars, Baptists and refuseniks did. They also championed fellow citizens:

Those who became known as rights-defenders where not the first to publicly invoke rights enshrined in the Soviet Constitution, to make use of samizdat or to organize petition campaigns and public demonstrations on behalf of victims of state repression. But they were the first to apply these techniques systematically and to people other than themselves.

Moscow based rights-defenders also served as “integrators,” to use the term coined by the late Peter Reddaway, a British-American political scientist who worked closely with the dissident movement from the early 1970s. What begins as a history of a small group of Moscow intellectuals soon becomes a description of the meeting of many dissidences — force fields with their own origins, historical development and locations — which overlapped but could not be reduced to any of the constituent parts.

This was an alternative Soviet Union, which prior to the development of the Moscow dissident subculture could only have met in the camps of the gulag:

The dissident movement fostered the mingling of individuals from different cities and towns, different nationalities, different belief systems: Russians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Crimean Tatars, Jews, Catholics, evangelical Christians, Russian Orthodox, atheist, neo-Leninist, social democrats, and those for whom all variants of Marxism were anathema. In certain ways, the movement replicated the staggering diversity of the Soviet Union itself.

Third, and crucially, the rights-defenders had a resource others lacked: contact with foreign journalists and other “Westerners,” including in the burgeoning international human rights movement. This was crucial: it allowed the various dissidences to mobilise support from allies in Europe, Britain, the United States, Australia and Israel. Without this support the movement for Jewish emigration, for example, would have been much less successful than it was.

The link to foreign journalists also had domestic implications. The infrastructure of the “voices” — the propaganda shortwave stations Voice of America, the BBC Russia Service, Radio Liberty and Kol Israel — allowed dissident texts to reach a much broader audience inside the Soviet Union than the personal networks supporting samizdat: typescripts would be passed on to journalists and sometimes within days the “voices” would broadcast them to anybody with a shortwave receiver in the land of the Soviets.

This transnational method reached people who were not part even of the outer reaches of the dissident networks, enabling Moscow rights-defenders to play a key role in creating the de facto pluralism of late-Soviet political opinion. Western attention, in turn, helped reinforce the dissidents’ own sense of exceptionalism and mission.

We can thus observe a process of virtual co-production by Moscow’s intellectual underground, the outside media, international activists, and cold war politicians of the myth of “the dissidents” as a Moscow-based movement rather than a much broader and more diverse all-Soviet phenomenon. With Nathans it has found its twenty-first-century chronicler and careful analyst.

His admirable book takes its title from a favourite dissident toast: To the success of our hopeless cause. And indeed drinking — along with talking and conducting sometimes complex romantic affairs within their own circles — was among the most important of dissident pastimes. In one 1972 pen portrait of this world, writes Nathans:

readers vicariously experience the sharing of samizdat, apartment searches, interrogations, arrests, vodka-inspired toasts…, interminable discussions of inner freedom and the meaning of life, and other rituals of dissident life. Most of the men are unemployed, having been fired from their jobs for signing open letters or distributing samizdat; most of the women work… Almost everyone is sleeping with someone other than their spouse.

Within this bohemian existence, the heroic moments that would bring international attention (and incarceration in prisons, camps or psychiatric hospitals) were few and far between. More important in many ways was another activity mentioned above: samizdat. The dissident movement was, first and foremost, a literary movement. And it was this unauthorised, underground literature — both fiction and non-fiction — that had the widest long-run impact and engaged the largest number of people, creating a thick layer of participation between the inner core of closely networked petitions signers and the broader underground public who listened to the “voices.”

Samizdat preceded the rights-movement proper and continued after it had been crushed. Its decentralised mode of production and distribution, in fact, was much less prone to central control and manipulation than the social media networks of our own time. The KGB never got a handle on it and it disseminated ideas of a remarkable variety of viewpoints and worldviews.

It was via the distribution of samizdat texts far beyond the dissident movement itself that the rights-defenders arguably had their greatest impact. These texts and the imprint on the minds of many Soviet citizens gave the movement for civil and human rights an afterlife that is still part of our present. As La Trobe University political scientist Robert Horvath argued two decades ago, “dissidents and their ideas influenced the course of Gorbachev’s reforms, and laid important foundations of a democratic political order.”

Nathans is somewhat reluctant to push this case too far, and he’s right to be cautious. For one, the movement’s afterlife was far from unidirectional: it did not lead neatly to more democracy and liberalism. As Melbourne Law School’s William Partlett demonstrated in his important 2024 study Why the Russian Constitution Matters, the rights-defenders did not confront the long Russian “tradition of state centralisation by proposing a new democratic Constitution that balanced power between the institutions of state or recognised plural sites of authority.” Rather, they tried to make a unified, presidentially dominated system legally accountable through law. Because it failed to see the central importance of negotiating disagreement through a system of checks and balances, this “anti-politics” of the rights movement left a deep imprint on the polity that would become Putin’s Russia.

Putin’s regime of “preventive counter-revolution” is not a lawless dictatorship. It is characterised by weak institutions but strong laws, constituting a rule by law flanked occasionally by extrajudicial killings (whose origins in the security services are always denied). We can see here an evolution of KGB tactics towards the rights-defenders. The original attempt to use formal judicial processes was a public relations disaster, as Nathans shows in detail: the rights-defenders turned the trials into spectacles demonstrating the hypocritical nature of the Soviet regime.

The KGB reacted by reaching for extrajudicial methods: intimidation, discrimination and the destruction of careers (including those of family members), forced emigration, administrative exile, or the forced incarceration in psychiatric hospitals. Their successors in Putin’s Russia — a Russia run by ex-KGBisty like the president himself — took a different path, one that promised more legitimacy and blunted the tactics of the rights-defenders: they adjusted the constitution and the entire legal structure, so it would allow repression within the boundaries set by laws. These laws, in turn, were passed by an elected parliament and constitutional change is legitimised by referendums. Despite these formal trappings of democratic governance, Russia today, according to Freedom House, is among the twenty-five least-free countries in the world.

Moreover, the dissident movement was considerably larger than the civil rights movement: it included all types of non-Soviet thought, including quasi-fascist strands of extreme Russian nationalism. This, too, was pointed out by Horvath two decades ago: his book bore the subtitle Dissidents, democratisation and radical nationalism in Russia. This aspect of Putinism, too, can be traced back to samizdat and debates in the Soviet underground.

Nathans is more positive about the legacy of the rights movement than the above sketch of its afterlives suggests. He points to the continued “invoking [of] existing laws and constitutional norms to contain the power of the state” in the “numerous protests during the first two decades of the Putin era.” One could highlight here the work of the NGO Memorial, a direct heir of the rights-defenders and a prominent victim of Putin’s legal repression of “foreign agents” in the run-up to his war against Ukraine.

Nathans is also more inclined to see Putin’s regime as “a feral state, where political opponents and those branded as traitors are as likely to be poisoned or assassinated as tried in a court of law.” Statistically speaking, that’s an over-statement: legal repression is the rule, assassination the exception. One list of “likely” government assassinations contains eighty-one people; Nathans cites some twenty thousand arrests, most of them temporary, of antiwar protesters alone by the time his book went to print. A recent count of political prisoners noted a likely number of 2000, while an independent group monitoring political repression in Russia (another heir of the dissident legacy) listed 5455 known cases since 2012, of which 3850 were current and 1656 in jail. (The database is updated daily; those figures were posted on 10 October of this year.)

This predominance of legal repression over extra-legal killings doesn’t make Putin’s regime less dictatorial, just more legalistic. But it makes less useful the tactic of acting as if the laws on the books actually apply than it was for the Soviet rights movement during its brief historical moment.

Today, the gap between legal claims and political reality are much narrower in Russia than they were during Soviet times. What does continue are the wider legacies of political solidarity with victims of the regime practised by dissidents and their supporters: providing legal defence, helping families deprived of breadwinners, publicising the abuses of the regime. Thus, we can still drink to the success of the hopeless cause of political opposition in Russia. •

To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause

By Benjamin Nathans | Princeton University Press | $69.99 | 816 pages