ONE hundred years ago today George Pearce of Western Australia rose in the Senate to deliver the second reading speech for the Commonwealth Electoral Bill 1911. Outside parliament, which sat in Melbourne in those days, it was a mild spring day with light rain forecast; inside, the senators were about to deal with legislation that would change forever how Australians participate in the electoral system.

The most dramatic measure in the bill was the introduction of compulsory enrolment for all adults who were eligible to vote. Like so many changes to our electoral laws, it was motivated by party self-interest and was bitterly contested, not finally becoming law until the following year.

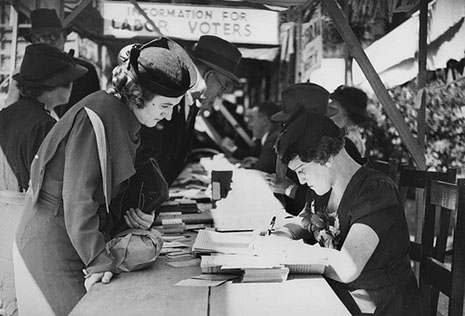

The Labor government of Andrew Fisher was concerned that the mobility of the workforce was leading to a decline in enrolment, disadvantaging Labor. In 1911, nearly 35 per cent of the workforce was employed in primary industries and was predominately pro-Labor. Compelling all eligible adults to enrol meant that itinerant workers – shearers, for example – would not lose the right to vote when they moved from electorate to electorate.

Naturally, the Liberal Party opposition objected. Its tactic was to oppose the measure and then challenge the government to go further and introduce compulsory voting as well. This position was also driven by self-interest: it was widely believed that women were politically more conservative than men but not as inclined to enrol and, more importantly, to vote. Compelling them to do so would naturally aid the Liberal Party.

Sometimes base motives can have unintended beneficial consequences, and this was the case with compulsory enrolment. It paved the way for a more complete, accurate and fraud-proof roll. It made it illegal to try to prevent people enrolling (a widespread practice in the United States both then and now). And it allowed for the drawing and redrawing of electoral boundaries on the basis of enrolled voters rather than population. The reform proved durable and, unlike compulsory voting (introduced in 1924), is now so uncontentious that no serious political player advocates its abolition.

But if we have compulsory enrolment, why is it that approximately 1.5 million eligible citizens are not currently on the roll – an increase from 919,627 in 2001? The question has a number of answers. There will always be those who deliberately dodge the roll, though the number is insignificant; Indigenous Australians are underrepresented on the roll, though again the number is relatively small; and a larger group is made up of people aged between eighteen and twenty-four. But by far the majority are those who were once on the roll but have been deleted because they have moved house – a significant number given that Australians remain a very mobile population.

The Australian Electoral Commission is charged with maintaining the roll, but it operates under strict conditions laid down in the Electoral Act. Until the 1990s, the chief method the AEC used to update the roll was the habitation review, in which casual staff visited all houses and flats to check the enrolment status of occupants (which it still does occasionally and in some rural areas). When changing work patterns and locked apartment buildings – not to mention savage dogs – rendered this method inefficient, the commission switched to the computer-based continuous update.

The AEC receives information from a range of agencies – motor vehicle registries and Centrelink, for example. When this data reveals that someone has moved out of the electorate in which they are enrolled, the commission is required by law to delete them from the roll. What it can’t do, however, is reinstate them at their new address, despite the fact that information from these sources means that it knows where they now live. All it can do is write to the elector enclosing a paper enrolment form and a stern warning that enrolment is compulsory. Only about 30 per cent of people return a completed form within the specified time period.

So the major cause of under-enrolment is essentially technical and it admits of a technical solution: a change to the Electoral Act to allow the AEC to “automatically” re-enrol a citizen at the new address and to inform him or her of the fact. After all, if the data sources are trustworthy enough to get a person de-enrolled then they must be trustworthy enough to get them re-enrolled.

Will it work? Fortunately we have some recent examples of automatic enrolment in operation. In 2009, the NSW parliament amended the state’s Electoral Act to introduce an automatic enrolment system known as SmartRoll, and it was used at this year’s state election with success. Victoria adopted a similar system in 2010 and trialled it at last year’s election without problems. Interestingly, both (Labor) governments that introduced it were defeated.

Unlike the concept of compulsory enrolment, automatic enrolment divides the political parties. While the NSW changes were supported by all parties, the Coalition voted against the Victorian bill and the evidence is that their federal colleagues would do the same. The main arguments made against automatic enrolment are, first, that it could be open to errors and hence compromise the “integrity” of the roll and, second, that individuals have a duty to maintain their enrolment and so the “nanny state” shouldn’t do it for them.

Would automatic enrolment advantage some parties over others? It probably would, because the demographic group that it would scoop up is currently more inclined to vote Labor and Green than for the Coalition. This is particularly the case among the mobile young, but it wasn’t the case in the past and may not be so in the future.

But would any party explicitly argue that it would be unfairly disadvantaged by a system that allows for the maximum number of qualified electors to vote? After all, we are a representative democracy. •

Brian Costar is Professor of Political Science at the Swinburne Institute.