“The next time you have one of those ‘singer-songwriters’ on your show,” a composer friend once said to me, “why don’t you just tell them to pull themselves together?”

At The Music Show on Radio National we pride ourselves on ruling nothing out: no sort of music is invalid if it’s powerful and well made. But certain styles seem destined to get up the noses of some of our listeners. Country music is one (it’s generally referred to as “hillbilly music” by its detractors), hip-hop is another, and modern classical music of the atonal variety — the kind composed by my above-mentioned colleague — is a third. But singer-songwriters also bring out the critics.

The odd thing here is that “singer-songwriter” hardly describes a musical style at all. In fact, I suspect it was stylistic neutrality that made it such a useful term. Back in the 1960s, when the likes of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell started out, they were thought of as “folk singers.” And it’s true both Dylan’s and Mitchell’s early days involved their singing traditional songs, but the label was always employed more loosely than that.

Rather quickly, “folk singer” came to denote anyone singing more or less anything, especially his or her own songs, with an acoustic guitar (in recent times, it’s made a comeback whenever acoustic instruments heave into view). But when Dylan went electric in the mid 1960s and Mitchell sang jazz a decade later, “folk singer” simply wouldn’t do. Hence, “singer-songwriter.”

So if “singer-songwriter” isn’t a musical style, what is it some people are objecting to? I suspect we have to go back a bit further than Bob and Joni for the answer to that question.

In twelfth-century France, trouvères (in the north) and troubadours (in the south) were perhaps the earliest singer-songwriters, and their subject, more often than not, was love and how bad it made you feel. These poet-musicians were mostly aristocratic men, the female objects of their desire obscured behind a wall of indifference, not to say contempt.

“My love of her imprisons me,” sang Bernart de Ventadorn (1135–1194), the most famous of the troubadours. “I contemplate death, when I look on her great beauty.” (There were also female troubadours, known as trobairitz, although, as you might guess, we don’t know much about them. We have, at a generous estimate, two dozen samples of their words — some of them, interestingly, also addressed to women — and a single tune.)

Yet while the twelfth-century melody and formal diction (in the Occitan language) render Bernart’s song distant and exotic to modern ears, we recognise the sentiments. The ardour, the jealousy, the anguish and pain, the oversharing… it’s the world of the singer-songwriter. The same themes might turn up in baroque operas, nineteenth-century German lieder, the songs of Broadway, jazz standards and rock & roll, but the manner of delivery is different.

In opera, in lieder and on Broadway, the words are not the singer’s; in rock & roll, the words might be the singer’s, but you could argue the singer is in character. With the singer-songwriter, however, you have a first-person art form: the singer is telling us his or her story (or seems to be), and as the listener sometimes it’s hard not to feel like a therapist. I think it’s that intimacy that discomfits many listeners. We don’t know where to look.

When Joni Mitchell’s Blue was released fifty years ago, Kris Kristofferson, shocked at how much of her personal life Mitchell had revealed, wrote to the singer begging her to “save something” for herself. And yet, just because a singer-songwriter is using the first person, it doesn’t mean she’s sharing confidences. “Confessional” is a word that’s often dragged out to describe the singer-songwriter, but while it might apply to the singer’s tone of voice, listeners shouldn’t assume they are hearing slices of autobiography. Recently on The Music Show, Joan Armatrading, whose songs are nearly all about love and nearly all in the first person, insisted they’re almost never about her. If Randy Newman’s first-person songs were truly “confessional,” he would be in prison.

Still, if you venture into this territory as a performer, you will quickly find yourself asked to explain how your lyrics relate to your life. It’s like being a novelist in that regard. The other thing you must prepare for is the naming of your influences. These are nearly always Dylan (for men) and Mitchell (for women), comparisons as pointless as suggesting a modern composer has been influenced by Stravinsky: you can’t be a serious composer and have learnt nothing from Stravinsky, even if you rejected it. So much for the anxiety of influence.

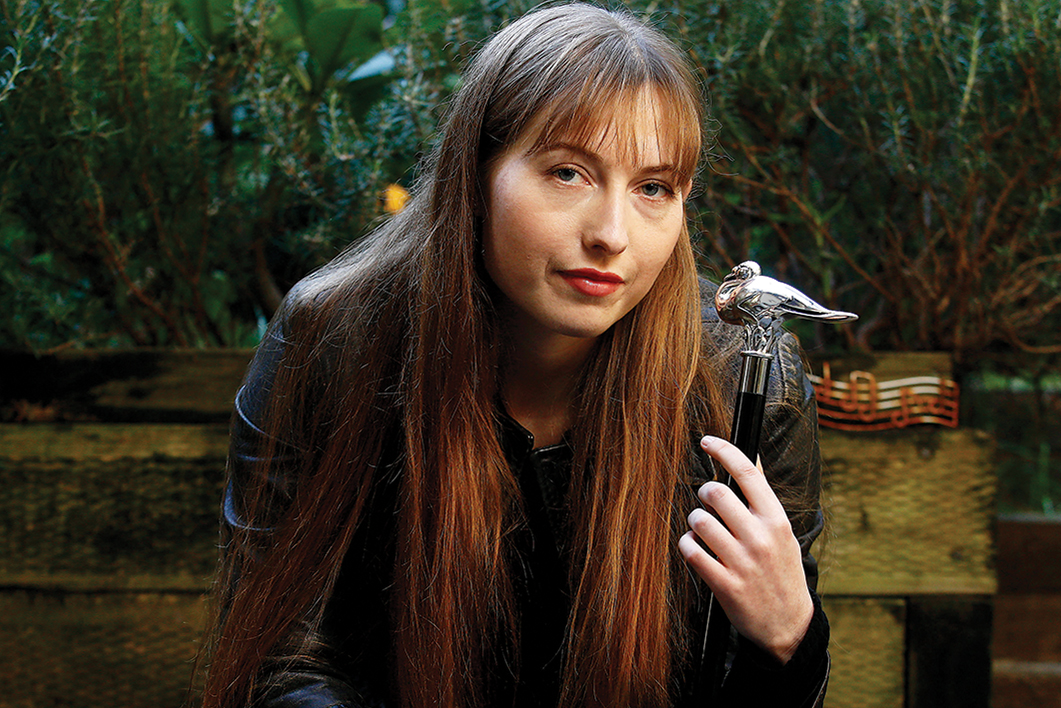

Joni Mitchell’s name has been mentioned quite a bit in connection with Medicine Man, the remarkably assured and accomplished debut album from Martha Marlow, though beyond Marlow’s use of vibrant open tunings for her guitar, it’s hard to hear much that she has in common with her Canadian predecessor.

“The anxiety of influence only happens after the fact,” Marlow says, “when some listeners want to try and identify specific influences and measure them. It’s an analysis that other people apply to your work to place you in a context.”

She’s not being defensive. Were Marlow the sort of artist much exercised about influence-spotting in her work, she’d hardly begin the final song on the album with “Yesterday,” followed by a McCartneyesque gap, and she certainly wouldn’t begin its fourth verse with “Yesterday… All my dreams seemed so far away.” Or maybe she’s teasing us.

Marlow would be the first to acknowledge that the songs on Medicine Man have been a kind of therapy for her, but not in the sense of sharing gratuitous confidences with an unsuspecting audience. She has had a lifetime of ill health, hospitalisation and operations. She lives with pain, and this music is her attempt to sing it away. “Come out Medicine Man / I feel you cutting in — I do / Do your worst, do,” she sings defiantly on the album’s title track, one of several up-tempo songs that transform her pain into energy, enhanced by the elaborate string arrangements of jazz bassist Jonathan Zwartz (her father) and the presence of a few other jazz luminaries.

On my favourite track, “One Flew East, One Flew West,” a rhythmically lopsided rant of a song, Marlow insists, “You never, never, never, never see what’s in my head.” I’m unsure who she’s addressing here, but it can’t be her listeners. We see all right.

“I don’t think being confessional is an essential tool,” she tells me. “I do think good singer-songwriters invoke real emotions and can bravely address things that are often unsaid. Those things don’t have to be factual or drawn from a real situation, but rather the singer-songwriter does need to draw on a real emotional experience. Like a good actor, who uses everything for their craft — for their character.

“Your life experiences become your palette — they are the colours you use, and which you mix up in different ways. You don’t have to literally speak to a specific experience, but anything you’ve experienced can turn up, and sometimes in unexpected places. You might have a powerful understanding of grief, for example, but that might reveal itself in a beautiful love song.”

You don’t need to know Martha Marlow’s story to appreciate her album. It is a collection of thirteen songs, filled with unpredictable melodic lines, surprising chords, propulsive rhythms, striking images, hope and, yes, love. The composer friend who recommended telling The Music Show’s next singer-songwriter to get a grip is now dead, but I venture to suggest even he would have admired Medicine Man. •