“In love, as in books, we are amazed at the choices of others.” Never did the words of sixteenth-century essayist Michel de Montaigne seem more apt than in 2017, when a gawping world caught up with what French voters had long known, that their soon-to-be president Emmanuel Macron was, at thirty-nine, a quarter-century younger than his wife Brigitte. A teacher of literature and drama in the northern city of Amiens, married with four children, Brigitte Trogneux’s heart had been won in the early 1990s by her pupil’s ardent, serious pursuit.

In outline their story echoes another, this one unknown but equally compelling as a symbol of love’s universal singularity. It unfolded almost three decades earlier, and was written about but soon forgotten. This article, inspired by both that book, The Monument, and its author, is a long-delayed response to a double oblivion, an attempt to make the silence around them audible.

The setting is an upper English milieu in the mid 1960s, mercantile and art-collecting. Here, too, a teenage boy falls headlong for a married woman, in this case ten years older. Bemused, then moved, by his implacable courtship, she feels herself sliding. As the new emotional forcefield around the unlikely pair slowly becomes apparent, a thorny prelude must be navigated before their world can take its own shape.

As with any couple, a lot had to happen to bring the pair, Justin and Ursula, together. Justin was the youngest of three brothers in an affluent family, his father partly of Hamburg-Jewish origins. At private school he had endured an obscure distress so severe that it led to his flight and then, when he was sent back, a suicide attempt. Now in his mid teens, athletic and handsome, he was coping well with a stint as trainee company manager in northeast England. More at home racing his mother’s Mini around west London, unspecified anger firing his boldness and disdain for convention, the all-or-nothing boy was out for life.

Ursula’s brush with Justin’s family came after years as a magnetic outsider amid the lofty conservatism of art-institution London — a world she had then sidestepped for partnership as a collector and dealer in antiquities. She had arrived as a polyglot Hungarian of Russian-Italian parentage, self-educated in the vast library of her father’s feudal estate near Budapest, a survivor of war, convent school, two morose families, internal exile, and being shot when escaping to Austria — armed only with a compass, dice and slim volume of T.S. Eliot’s poems — during the 1956 revolution.

Her luck held: the British embassy official in Vienna was a fan (“That little book is worth all the passports in the world”), and soon she was on her way, complete with an introduction to Oxford’s art history department. Waiting for interview there, she met another day-visitor, the renowned art historian Anthony Blunt, head of London’s Courtauld Institute, who grasped her star quality and seized the chance to recruit her. (A Soviet agent and talent-spotter from the 1930s to the 50s, Blunt was an expert at this too.) At the Courtauld she married Kenelm Digby-Jones, a mature student a decade older, her scholarship and allure well matched with his ambition and fatalistic humour, not least when it came to their dealership.

From her blonde mane to her tangy wit Ursula burned charisma. She was a virtuoso, but an unhappy one. Their private double act, loving on his side, inwardly restive (and affair-rich) on hers, was struggling. Behind the impermeable, self-protective screen that was concealed by her sparkling presence, Ursula had lost purpose. Yet the business prospered, and when Kenelm sold some Georgian-era furniture to Justin’s parents, the couple became weekend guests at their historic estate, west of London, when the sixteen-year-old happened to be there. Justin’s postscript to a long Saturday morning walk and late-night conversation with Ursula, art the focus of both, was to slip a post-goodnight declaration of love under the marital door.

“An element of the shrine”

The path from there was circuitous: letters, heady summer days on the Mediterranean (Justin’s French crammer being a manic motorbike ride away from Ursula and Kenelm’s holiday villa), a farcical road trip by the trio from Athens to Palmyra to buy artefacts, Justin’s desperate hunt for Ursula in Rome when she briefly faltered. Money worries, an obstacle to the future the couple were already planning, interceded then lifted as Kenelm agreed a settlement and Justin’s father brought forward by four years an allowance now to be paid when he turned twenty-one.

Both pieces of good news arrived when the couple were in Mexico, having travelled from Luxor via Cyprus and Sudan. Justin’s material sufficiency, well husbanded, would underpin their freedom to set the contours of a nomadic but regulated lifestyle, maximum sensuousness its chief requirement. From the outset, Ursula’s greater life experience and learning, and her choice of their itinerary, went with a deliberate yielding to Justin in other areas: sexual, logistical, bureaucratic and even linguistic, as his fluency in Greek, Italian and Arabic would come to equal her own range.

The core elements of their voyaging would endure for fifteen more years, during which Justin and Ursula would spend every moment, the odd hour or two excepted, side by side. Their relationship was conducted with stylised precision and, evidently, undimmed erotic passion, a realm of the senses crafted from sheer complementarity. A pleasing hotel or rented room, fastidiously graced with favoured objects collected on their travels, a good local restaurant or two, markets and opportunities for cooking, an intriguing library, a decent gallery, historical sites, alternate discovery (they sought novelty) and familiarity (they longed to return): these were the essential, almost austere, ingredients.

An intimate, peripatetic world acquired its own seasonal cycle and fixed points. At Nysi in Greece’s southwestern Peloponnese, they bought a headland with a steep drop to the sea, inaccessible by road, where Justin secured permission to erect a small house of vernacular type and lay out gardens and paths, leading a team of local men he had come to know. After spring and summer there they moved to a tiny flat in the Trastevere district of equally beloved Rome, purchased as a base for concerts and to explore the city’s cultural treasures. Autumn brought trips to Paris for theatre and London to see family and friends, then (two years in three) three months of travelling further afield: Cambodia and Laos, India and Pakistan, the Maghreb, west-central Africa, Brazil, the Andes. In the third year, they would explore other parts of Europe, perhaps Spain and Germany — but never Ursula’s long-discarded fatherlands to the east.

Ursula and Justin fitted no tribe: artists and writers of the kind clustering on Hydra and other Greek islands around the period, experimental hippies on the eastward trail (about whom Ursula was amusedly scathing), lotus-eaters or jet-setters, semi-exiles with publishing channels to the metropolis. Patrick Leigh Fermor, a resident of Mani down the coast, knew Ursula in London days but had no idea she had a home in Greece, while the self-absorbed distance of Bruce Chatwin, former confidant, echoed Ursula’s own.

A nearer affinity might be with romantic pre-railway travellers from northern Europe’s elite who discovered civilisation’s patrimony in the noble ruins of, well, Greece and Rome, whose pleasures included “indolent delicious reverie.” This self-conscious relapse would place the couple as all the more out-of-time even in their own time. Indeed, TV, pop music, advertising and the sixties’ politics made no impression on Ursula and Justin’s world. It’s a surprise to find Ursula, in Bangkok, going as far as “reading the Economist on the troubles in Laos.” Also a misleading one, in that by principled design they knew everything they needed to and ignored the rest. In retorting to a suggestion that Ursula was anachronistic, the brilliant if unreliable Chatwin, deep time in mind, ventured, “No — she was futuristic.” The grand tour was no intermission, but life itself.

Still, their space of freedom was timebound, as their itinerary foreshadows: pre-genocide Cambodia and Darfur, pre-revolution Iran, prewar Afghanistan and Iraq, pre-terrorism Egypt, Niger, Mali. At the end of the 1970s the world lurched. Later explorations in Sudan pushed Justin and Ursula towards a disharmony that goes to the very root of their mutual devotion. At some level hard to fathom, the rift contains too the inrush of forces already jolting the larger world.

“Nudging closer to the truth”

That protracted episode, taking place mainly in southern Darfur, between Nyala and El Fashir, 700 miles southwest of Sudan’s capital, and afterwards in England, Rome, Nysi and Khartoum itself, is the tragic culmination of Ursula and Justin’s story. A book composed in the aftermath, vital source for the above account, ends with a scrupulous investigation into these months’ often-elusive events. Published in 1988, The Monument was written by T. Behrens, elder brother of Justin by eleven years.

Reaching far across space and time to track Ursula and Justin’s evolving interior lives, The Monument is distinguished by its composite flavour. An interplay of biography, memoir, analytical narrative and (in effect) journalistic inquiry, it draws in turn on three unpublished texts: Ursula’s journals, entries from which compose a third of the book, her lightly fictionalised version of the crisis (also called The Monument), and Justin’s lengthy homage to her, entitled Style, again incorporating Ursula’s writings. The lucidity, subtlety, humour and cultivated self-awareness with which this mosaic is handled make for an indelible work.

Its opening lines nail its promise: “I heard that my sixteen-year-old brother was involved with a most exotic creature, some sort of Hungarian countess, married and probably a spy. Having hardly seen him since his voice had broken, I was curious to know more.” The next page glows with a spellbinding portrait of Ursula, of which but a taste can be quoted:

She would talk about anything to anyone. She had a most charming and discreet technique for extracting people’s life-histories. Like a skilful interviewer she’d lay an extra pertinent question whenever the subject seemed to be running out of steam. She was almost a better listener than talker, and that’s saying something. And her intelligence was infectious, you raised your game like some random qualifier at Wimbledon taking a set off the defending champion.

Having found that the “little brother to whose existence I’d given so little thought was suddenly involved in a scandalous adventure with one of the most original women I’d ever met,” closer acquaintance would result in no less perceptive scrutiny, increasingly freighted by the sorrow that, alongside the need to know and record, is the book’s spur:

If one single quality can be said to have directed my brother’s life, it’s the kind of moral and physical courage often to be found in the characters of men of action… The analogy of the knight isn’t wholly fanciful — there was something archaic about him, discernible in his identification with primitive culture, his immaculate clothes, even the occasionally eyebrow-raising stiltedness of his language. He really did resist the twentieth century. I’m not entirely at ease with it myself, but like most people I inevitably feel obliged to give it the benefit of the doubt. But Justin was both a hero and my brother… My frustration with the distance he kept from me hardened slowly but surely into an unadmitted jealousy of his heroism.

Ursula and Justin’s coupledom is lit with empathic acuity:

If Justin had idealised Ursula he would hardly have forced himself on her either at the beginning or when she wrote him a goodbye letter in Cairo. Instead he recognised with absolute certainty, as if he were in possession of private information, that she needed him for her survival. And Ursula, although it took her longer to commit herself — which wasn’t surprising considering her comparative lack of freedom — finally did so in the same spirit of absolute recognition.

Its dialogic element further enhances the work, as when the author’s own “rather harsh conjectures” on why Ursula, “having been gregarious, hilarious, cynical and all-questioning, became reclusive, serious, mystical and omniscient,” are tested against the scepticism of her good friend Eve Molesworth, or when he hands its closing section to Riri Howse, valued confidante of Justin in Khartoum, on account of “the disinterested love, the honest indignation, and the unflinching regard for the facts [her words] conveyed to me.” The Monument’s diversity of voices itself radiates wisdom and confidence.

The Monument’s luminous narrative opens up Ursula and Justin’s lives without ever claiming or diminishing them, enabled by an ingenious kaleidoscopic structure around its characters’ names. This melding of content and form is the key to the work’s haunting effect, in turn augmented by the crucial absence of photographs (Justin having taken many of Ursula), and even T. Behrens’s spare moniker and biography.

The Monument should have been recognised as pioneering, a sui generis classic, but was not. It had few friends and no champions. Amid the burgeoning fashion for travel and romance in exotic settings, the characters were too odd, real, disturbing or even risible: a pair of self-absorbed loafers on an endless gap year, she a gold-digging voluptuary catapulting from murky Europe to the esoteric London art market, he a privileged, precocious toy boy. A snooty notice by the Olympian editor Karl Miller in the London Review of Books damned with mispraise. Oblivion called.

In fact, morally intelligent and thus searing versions of such caricatures are already weighed in a steadfast narrative true to the emotionally complex lives that are The Monument’s subject. Ursula and Justin as literary dilettantes, as children in a game called Art (“Les Enfants Terribles in the territory of Le Grand Meaulnes”), as “a bit of a joke” in the family circle, as leaning to hippiedom in their first two months in Sudan; Ursula as a dead ringer for Mikhail Lermontov’s anomic dreamer Pechorin — nothing is avoided in the book’s crystalline search for the entangled heart of things.

“Does this gentleman exist?”

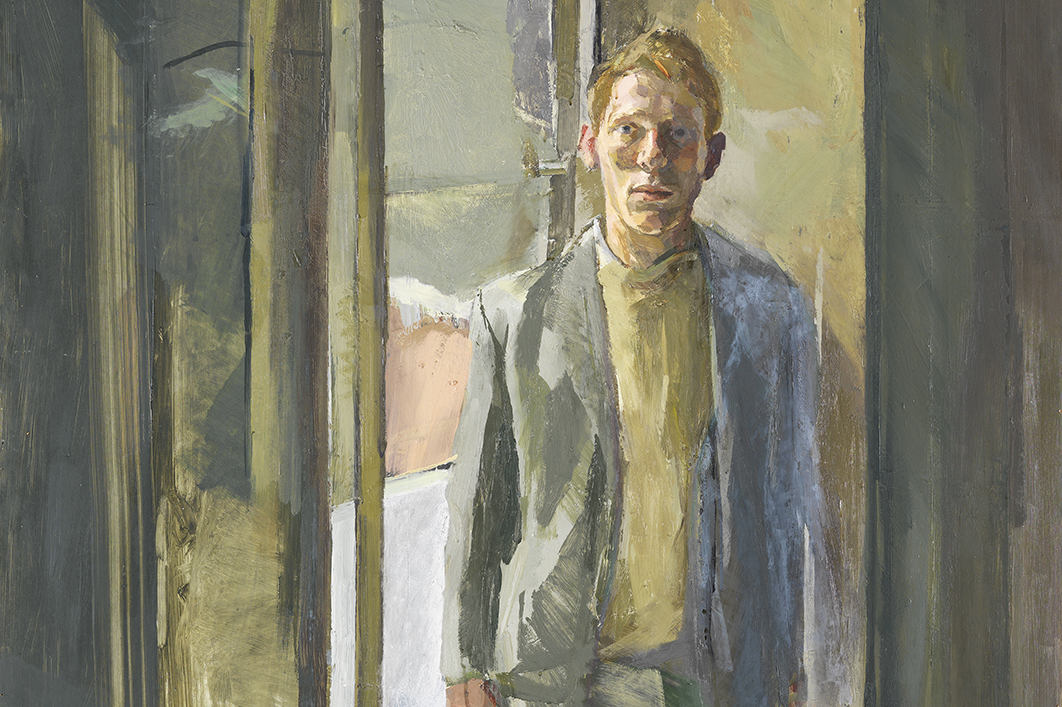

The book’s erasure would be matched by that of its author, the figurative painter Timothy (Tim) Behrens, a seventeen-year-old student at the Slade in the mid 1950s when he became protégé, friend and (see Red-Haired Man on a Chair) model of Lucian Freud, in a carousing, priapic relationship with an acrimonious end. His, at best, shadowy life in Britain’s art world is illustrated by his near invisibility even in Martin Gayford’s excellent Modernists & Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney and the London Painters, published in 2018, and his scarce mention in or omission from many surveys of the 1950s and 60s “school of London” (at most a drinking club) to which he notionally belonged.

After Tim’s death in February 2017, the Portugal-based artist António Cerveira Pinto, a long-term advocate of Behrens’s work, was alone in noting this absurd situation. (“Does this gentleman exist? I still don’t understand why Tim Behrens is missing in all surveys of British art from the early sixties.”) The meagre and perfunctory obituaries (the Times’s an exception), filled out with tattle, admittedly juicy, on earlier years — La Ronde in the territory of Caravaggio — sealed the pact of silence on his earlier work, not least later decades’.

At least Geordie Greig’s encomium to Freud, Breakfast with Lucian, published in 2015, contains morsels from an interview with Behrens conducted in A Coruña in Galicia, northwest Spain, where he lived for thirty years. “I could not believe anyone could be so cold. I had seen (Lucian) as a substitute for my father who had been a complete bastard. I truly loved him and that was what made it so painful when we had our bust-up.” Behrens said elsewhere that Freud, fifteen years older, “adopted me, but then threw me out of the nest, as birds do.”

Just a tad more prosaically, it was when he was Sunday Times literary editor from the mid 1990s that Greig sent me a charming postcard rejecting my submission on The Monument to the paper’s series on underrated books. This bittersweet memory was later eclipsed by the pleasure of exchanging letters with Behrens and receiving from him a copy of an early collaboration with the photographer-doctor Federico García Cabezón, whose images of Galicia are accompanied by Tim’s limpid poems in Spanish.

Behrens’s novel of memory, Poniéndose ya el abrigo (Putting the Coat On) — translated by the peerless Roger Wolfe from English, but not yet available in that language — is well worth seeking out. His editor and friend Eduardo Riestra contrasts this story of his “search for a place to live in” with El Monumento, that “magnificent, rigorous, respectful, but very complicated work.” Both books are published by Ediciones Del Viento in A Coruña, where Tim Behrens was long a convivial and esteemed figure in the area’s fertile cultural scene. “I prefer to belong to the School of La Coruña,” he wrote in 2003.

He was survived by the printmaker Diana Aitchison and, among five children, the graphic designer Charlie Behrens, whose book of interviews is also yet to appear. Besides Behrens, its subjects include the Slade alumnus Nicholas Garland, Britain’s greatest living political cartoonist, and the writer Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, indispensable figure in The Monument’s own hard road to publication.

“Because I do not hope to turn again”

The Monument’s cast bears the imprint of history, family, class and England, all of which in varying degree drive a longing to flee yet exert a continuing hold. These impulses, replicated in the coil of shelter and freedom that sexuality and love offer, weave through its characters’ lives.

Thirty years on, the book’s blend of genres extends to documentary and even social history. If Ursula’s early trajectory, fittingly unique as it was, is also part of the 1956 Hungarian diaspora and Britain’s immigration experience, Justin’s thirty-four years could be a case study in the ambiguities of Englishness and class. The teenager rejected England early and, mindful of the family’s continental heritage, always called himself European. On a mid-sixties stopover in Naples on the way to Ursula with photographer friend Tom Hilton, the long-haired pair were threatened with “extermination” by actual fascists “because you are existentialists.” At the same time, his weekends home from Newcastle featured mimic-laden vignettes of his factory’s workers, while in Nysi — barely twenty — he would lead his fellow housebuilders with officer-like responsibility.

His own input on that job was unremitting, “a real labour of Hercules,” said Riri Howse, who with husband Christopher would purchase the Nysi cottage. When the Greek-English couple, a rock of support to Justin in Khartoum, came to England to finalise matters, Riri noted Justin’s demeanour in the land of his birth. “All the time he seemed aloof from the natives as if he could barely tolerate them.” In London, “we went to Fortnum and Mason’s to buy cheese and chocolate for a friend of his. I was amused to see that he behaved in a typical English upper-class manner. It was not put on, he switched to it automatically, without realising it. I told him about it, and he laughed and shook his head.”

The same Justin had invited to Culham Court the venerable Sheikh Mohammed, father-in-law of the Nyala police chief Ali who was at the centre of his and Ursula’s Darfuri world. When this majestic figure toured the property and reached a room commanding a verdant arc to the Thames, he was moved to offer advice to Justin, who reluctantly translated from Arabic for his mother: “He says that, although I am like a son to him, I belong here among all this beauty, and that I should not go back to Sudan.”

The Monument is now also an episode in these buildings’ life. Culham Court was sold in 1997 by that matriarch, Felicity Behrens, to whom the book is dedicated, and currently belongs to a Swiss-born financier with big plans for it, while the Nysi cottage also changed hands to become a holiday home (“beautiful secluded tranquil paradise on the sea with stunning views of mountains and islands”).

Might Ursula and Justin equally have been able to prolong their world by ceding to, then navigating, the more fluid if rockier one forming around them? Justin today, still only seventy, as a socially minded entrepreneur or producer? Ursula as an acclaimed niche gallerist, her enigmatic past more than ever an asset, her style signifier an ivory monkey neck chain, Justin’s part of the ritual exchange on their first night of lovemaking in Cap Ferrat over half a century ago?

But changing from within, and in sync, is hard, even more for such a couple. T. Behrens describes his litany of “if onlys” as “whines of impotence, whimpers of desolation, which are no help at all in deciphering the network of contradictions that is the map of an individual’s destiny.” The actual ending governs all.

In its own journey, The Monument renders Ursula and Justin ageless, powerfully so in requiring no surrender to myth. Here they are sauntering on a Rome street, ahead of the author and his then wife Harriet, the chance sighting recorded with André Kertész–like immediacy:

They too stopped, exactly as if we had turned a switch. They turned to face each other without, however, noticing our presence fifty metres behind them. Justin cupped one hand round the back of Ursula’s neck in its sheath of silky, yellow hair, while he tenderly stroked the curve of her jaw with the other. They looked fixedly into each other’s eyes. There was a feeling of slow motion — he was caressing her with an intimacy all the more erotic for being slightly distanced. No question of anything like a clinch, nor had they in any way ruffled their immaculate grooming. After a minute or two, when we didn’t dare move for fear of being caught in an act of blatant, if inadvertent, voyeurism, they slipped an arm round one another’s waist and resumed their leisurely progress towards the Tiber. We quickly retreated to the Piazza Farnese, where we burst out laughing — though both of us knew that what we had just seen was no laughing matter. It was the laughter of relief.

Amazement entertains or appals as well as entrances. The Monument, a book about love, can do the lot. If only there is room left in this world for it and discerning readers to meet. •