There are close to 500 people in the back garden, and it seems all of them must be chanting. “We want Gough! We want Gough!” The noise is deafening. The crush is at its worst near the sunroom door, where the new prime minister is expected to appear any minute to make a victory statement. Radio and television reporters and newspaper photographers are scuffling among themselves and with party guests to get close to the doorway. A huge, bearded man from the ABC is trying unsuccessfully to move the crowd aside to clear the area in front of the camera which will take the event live across Australia.

“Get your hands off me,” an angry photographer in a pink shirt snarls at a television reporter. Punches are thrown. Blood spurts from the nose of a radio journalist. “Come on, simmer down,” people shout. Someone warns the pink-shirted troublemaker: “This is going all over the country, you know.” More punches are thrown. “Go to buggery, punk,” the photographer screams at a member of the ABC crew. “This is not the ABC studio.”

One of the Labor Party’s public relations team, David White, is pleading with the mob to “ease back, make room for the camera.” Tony Whitlam, the six foot five inch son of the Labor leader, moves in to try to break up the scuffles. He is patient at first, then he flushes angrily and clenches a fist. A Whitlam aide, Richard Hall, places a hand on his shoulder and says, “Easy, Tony.” David White motions to a rather large member of the Canberra press corps and whispers, “Stand in the doorway and look imposing while I get some policemen.”

Inside the house, oblivious to the violence on the patio, Gough Whitlam and his wife, Margaret, are cutting a victory cake. In the icing are the words “Congratulations Gough Whitlam, Prime Minister, 1972.” The party workers sing “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” but the noise from the garden drowns them out.

“We should have thought of barricades,” mutters Richard Hall, as he and other members of the Whitlam staff hurriedly make new arrangements for the prime minister–elect to face the television cameras inside, away from the mob. Party guests are cleared from the sunroom. The big ABC camera is lifted through the door. Lights are set up. Mrs Whitlam appears and is questioned by radio and TV men, but her answers are inaudible more than a few feet away. Whitlam’s driver, Bob Miller, fights his way through the crush with a white piano stool for his boss to sit on.

About forty media people are packed into a room that measures no more than twenty feet by fifteen feet — together with the TV camera, the lights, the microphones. The heat is overwhelming. Television reporters sweat under their make-up. Then, at 11.27pm, Gough Whitlam squeezes along the passage and takes his place on the stool.

Radio reporters lunge at him with microphones as he begins to speak. “All I want to say at this stage is that it is clear that the majority given by New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania is so substantial that the government will have a very good mandate to carry out all its policies. These are the policies which we have put in the last parliament, and throughout the campaign we did not divert from them, we were not distracted from them, and we are very much reassured by the response the public gave to our program… We are, of course, very much aware of the responsibility with which the people have now entrusted us.”

The TV and radio men begin to fire questions about the actions he plans as prime minister, but he stops them. “I can’t go on answering questions like this… I have to wait for a call from the governor-general.” But it is enough. He has claimed victory, and now he moves out into the garden to mingle with Labor supporters, friends and neighbours who have attended similar parties at the unimposing Whitlam house in Albert Street, Cabramatta, every election night since he moved there in 1957.

Twenty-five miles away, at Drumalbyn Road, Bellevue Hill, a far grander residence in a far grander suburb, William McMahon has watched the Whitlam performance on television. He had been about to go outside to face the cameras himself, but now he must wait another ten minutes or so. Early that afternoon one of his press officers, Phillip Davis, anticipating a Labor win, had drafted a statement conceding defeat. At 10pm he and speechwriter Jonathon Gaul had retired to the family room in the McMahon home to dictate a final version to a stenographer.

Now McMahon reads it over, scribbling in a note at one point to “thank government supporters.” Then he says, “All right, let’s get it over with.” A staff member asks if he is sure he knows what he is going to say, and he nods. Davis asks Mrs Sonia McMahon if she minds accompanying her husband. “Nothing would stop me going out with him,” she says.

Outside the door are the cameras and a tunnel of pressmen. To the right nearly 200 well-wishers — neighbours, party supporters, curious sightseers — are gathered. McMahon walks out. His wife, looking strained but dry-eyed, follows. “Mr Whitlam has obviously won and won handsomely,” says the politician who has led the Liberal–Country Party Coalition to its first defeat for twenty-three years.

“There can be no doubt about the trend in New South Wales and Victoria, and they show a decisive majority for him. I congratulate him, and I congratulate his party, too. For my own part, I accept the verdict of the people as I always would do… Mr Whitlam must also accept the fact that we are an opposition that will stick to our Liberal principles and will give him vigorous opposition whenever we feel that he is taking action which is contrary to the interests of the Australian people.”

He thanks those who voted for the Coalition, and then adds, “Above all, I want to thank my own staff who have been driven relentlessly over the last few months and have stuck with me, they’ve helped me, and they’ve never wilted under the most heavy and severe oppression.” Finally: “The election is gone, it is over, and Mr Whitlam is entitled to be called upon by the governor-general to form a government.”

It has been a dignified statement, delivered with scarcely a tremor in his voice. The man who has gone through an election campaign reading speeches from an autocue has departed from his prepared text, and improved on it. He has been more generous in his references to his opponents than Davis and Gaul had been. The appreciative remarks about his staff are totally unscripted, coming as a shock to people who in the past have felt themselves to be little more than numbers to their employer.

McMahon refuses to answer questions on the reasons for the Coalition’s defeat. “That’s something for deep consideration,” he tells the reporters. Then he turns away and, with Mrs McMahon, plunges into the crowd clustering around the wrought-iron double gates and across the gravel driveway. For several minutes his diminutive figure is lost from sight as he moves among the well-wishers, shaking hands and accepting condolences.

Gough Whitlam and William McMahon spent polling day, Saturday 2 December 1972, touring booths in their electorates. There are forty-one booths in the sprawling electorate of Werriwa in Sydney’s outer-western suburbs, and Whitlam, accompanied by his wife and the Labor Party’s radio and television expert, Peter Martin, visited all of them.

Mr McMahon, too, visited all thirty-three booths in his seat of Lowe, not far away but closer to the city. On his way home he dropped in on several booths in Evans, one of the marginal seats the Liberals feared they would lose. The sitting Liberal member, the navy minister Dr Malcolm Mackay, was one of his closest supporters, and McMahon wanted to help him if he could, even at that late stage. Then McMahon returned to Bellevue Hill, had a swim in his pool and settled down to wait with his staff and a few friends. Whitlam went back to Cabramatta to prepare for the party.

The Whitlam election night party is by now a tradition in Werriwa. For several months before the 1972 election, members of Whitlam’s staff — particularly his press secretary and speechwriter Graham Freudenberg — had been trying to persuade him to change the venue, to hold it at a club or a hotel. With a Labor victory likely, they foresaw security problems.

The crowd, they warned, would be too big for the small cottage and its pocket-handkerchief garden. But Whitlam insisted the function would be held at the house as usual. The party workers in the electorate expected it, he said, and that was that. But he made one concession. He agreed that, while the figures were coming in and he was studying the count, he would retire to the Sunnybrook Motel two blocks away.

Mrs Whitlam supervised the arrangements for the party. A bar was set up in a corner of the back garden. In another corner was a makeshift toilet labelled “gents.” She explained proudly to early arrivals, “It’s a two-holer. Have a look at it.” At various places in the back garden were five television sets, their cords snaking among the shrubs to power points inside the house. On the roof, television technicians set up a microwave link disc, giving the house a science fiction appearance. There were three television outside broadcast vans in the street near the front gate.

On the patio, the television men had placed a ten foot high microphone to pick up the sounds of the party. It produced considerable amusement. “Have you seen it?” Peter Martin kept asking people. “It’s the Gough Whitlam microphone stand, the first one we’ve found that’s tall enough for him.” There was one television camera set up high, near the bar, which could sweep the whole garden. The other, on the patio, was to record whatever Whitlam might say in either victory or defeat. One of the bedrooms had been taken over as a press room, with half a dozen telephones on a long table.

Preparations in Bellevue Hill were more modest. At the insistence of Phil Davis the Liberal Party provided a tent for the press beside the swimming pool, with a few tables and chairs. Davis had stocked it with a car fridge and $30 worth of beer. There were no television sets until the TV men themselves set up monitors, but Davis left his transistor radio with the journalists mounting the vigil which, as the night wore on, they dubbed the “death watch.”

In the lounge room were two telephones and two portable television sets for McMahon and his close advisers. In the family room another set had been provided for the stenographers and Commonwealth car drivers on his staff.

McMahon appeared briefly to talk to the press and the cameras before the figures began coming in. He was confident of victory for the Coalition, he told them, and had no worries about his own position in Lowe. No one could be sure whether he believed it, but he appeared jaunty enough, immaculate in his freshly pressed blue suit, white shirt, crimson tie and carefully polished shoes. With a wave he disappeared into the house, not to be seen again for more than three hours except in silhouette through the lounge room windows.

It was a strange atmosphere inside the house, tense but not emotional. McMahon settled down at one telephone. John Howard, a vice-president of the NSW Liberal Party, remained glued to the other. Davis, Gaul, McMahon’s private secretary Ian Grigg, Mrs McMahon, and several friends of the family watched the results on the television sets. Little was said.

McMahon received frequent reports on his own seat from scrutineers, and remained outwardly calm even when it looked as though he might lose it. Only once did he snap at a party worker when conflicting figures were phoned in from Lowe. He was in constant contact with electoral officials in Canberra, and with the federal director of the Liberal Party, Bede Hartcher, who was in the national tally room. From time to time Howard handed him figures. Davis and Gaul kept him up to date with the figures coming up on television. He scribbled on a notepad, calculating the government’s position and appreciating it far better than anyone else in the room.

McMahon has the ability to “feel” a political situation before most other people. It is one of the reasons he was able to survive so many crises in his turbulent career, the talent that earned him a reputation as a political Houdini. He got the “gut” feeling that told him the government was heading for defeat almost as soon as the early figures began to come in. He was ready to concede by 10pm, but wanted to make sure Lowe was safe before he faced the questions of the press.

Hartcher and other Liberal officials urged him to wait, telling him there was still a chance the government could scrape back, but he knew better. Then [Liberal frontbencher] John Gorton appeared on television, admitting that Labor had won. The customs minister, Don Chipp, also conceded. And the treasurer, Billy Snedden. McMahon knew he had to go out on the lawn, where the cameras and the journalists were waiting like vultures. But first he had a cup of tea. Mrs McMahon handed it to him, and those in the room watched as he spooned in the sugar. His hand was steady.

The ordeal of the statement over, McMahon returned to the small group in the lounge room and sat quietly for a time. Then he perked up. “Oh well, that’s it,” he said. “We’ve got some champagne. Let’s open it.” From then on the mood was almost one of relief that it was all over. Party workers from Lowe dropped in, and some NSW Liberal Party officials. Outside, their work over for the night, journalists and TV men were drinking in the tent. Davis and Gaul joined them.

At about 1am a young woman broke through the security screen around the McMahon house by clambering over a fence from next door. She joined the press group, and gushed over McMahon and his wife when they emerged soon after for a final, off-the-record chat. Only once during the night did McMahon lapse into introspection and ask rhetorically, “Where did we go wrong?” He did not offer an answer to the question. Later he said, “At least we didn’t lose as many seats as in 1969.”

Whitlam’s staff spirited him away from his home to the motel soon after 8pm. Very few people knew where he had gone. It was well over an hour before a group of journalists and photographers tracked him down, and they were kept locked out of the room where he was studying the results.

Around the room were four television sets tuned to different channels. At one end was a table with a bank of seven phones. Richard Hall was constantly on the phone talking with scrutineers and candidates round the country, getting figures before they were posted in the tally room. Clem Lloyd, Lance Barnard’s press secretary, phoned through figures from the national tally room at regular intervals. David White was also manning phones.

Mungo MacCallum, the Nation Review journalist, had been coopted to work a calculating machine. Whitlam sat in an armchair facing the television set tuned in to the ABC, but frequently he screwed himself around to watch the other sets as they showed new figures. Peter Martin was there. Graham Freudenberg sat on the bed listening intently to the analysis of British psephologist David Butler on Channel 7. Another of Whitlam’s press aides, Warwick Cooper, hovered in the background. His private secretary, Jim Spigelman, was making calculations on a notepad.

Bob Miller poured glasses of beer and orange juice for the workers. Also present was Ian Baker, press secretary of the Victorian opposition leader, Clyde Holding. There was whispered conversation. “It’s starting to look as though the DLP vote is down in Victoria,” said Martin at 8.45. “A trend is developing to us in the outer suburbs,” Hall told Whitlam a few minutes later. “We’ve got Phillip,” Freudenberg announced at 8.50. Placing his hand over the mouthpiece of his phone, Hall read out the first figures for MacArthur and told Whitlam, “It looks like Bate is going to poll well.” Less than a minute later he interrupted another phone conversation to tell Whitlam, “There’s no doubt about it, the DLP is ratshit in Victoria. They’re going down.”

But Whitlam remained cautious. When the ABC showed figures for Mitchell and compere Robert Moore told viewers that Liberal member Les Irwin was trailing his Labor opponent, Whitlam commented, “It’s still not marvellous.” Hall announced. “There’s a clear absolute majority to us in Hume,” but Whitlam replied, “Later figures always go against us. We’d have to have a very good lead.” One of the TV screens showed Liberal Alan Jarman trailing in Deakin, but Whitlam said, “He’ll still get in, though.”

Whitlam showed little emotion as he stared intently at the television screen, until a little after 9pm when Hall told him, “I reckon we’ve won Casey, Holt, Latrobe, Diamond Valley and Denison.” On the TV set tuned to Channel 9, [journalist] Alan Reid was saying, “If this trend continues I’d say Labor is home and hosed.” Then Whitlam allowed himself a smile, and sprawled back in his chair clearly more relaxed.

At that point he knew he had almost certainly won. There was irony when one of the channels rescreened McMahon’s earlier interview, showing him saying, “I feel more confident than I did this morning.” But there was bad news, too. At 9.05 MacCallum looked up from his calculator and remarked, “In Bendigo David Kennedy is only on 48 per cent. He’ll go to preferences.” Whitlam became sombre again as he said, “But will he get them?” At 9.15 Whitlam gave Hall permission to phone the Labor candidate in Denison, John Coates, to congratulate him on a certain win.

Then Hall reported that Labor scrutineers had no doubt the party would win Evans. At 9.18 one of the staff let out a cry of “Jesus!” as figures for Flinders on one of the TV sets showed the labour and national service minister, Phillip Lynch, fighting to hold the seat. Then at 9.20 MacCallum performed some more calculations and announced to the assembled company, “I think we can send the white smoke up the chimney now.”

From then on, the mood in the room was one of elation. “Welcome home Victoria!” said Spigelman as one of the television computers came up with a printout showing a swing of 6 per cent to Labor there. NSW party officials had told Whitlam there was a good chance of a Labor win in the Country Party–held seat of Paterson, but he had not believed them. At 9.26, when Freudenberg said, “They were right about Paterson,” he sprang out of his chair with an astounded cry of “What?”

He rubbed his hands together gleefully when Freudenberg hold him a few minutes later, “Look. Race is in.” Race Mathews, his former private secretary, had a clear lead over the minister for the environment, Aborigines and the arts, Peter Howson, in the Victorian seat of Casey. At that point, Bob Miller was sent to fetch Mrs Whitlam, and as soon as she arrived Hall popped the cork from the first champagne bottle. Glasses were clinked all round. “Many happy returns,” said Mrs Whitlam.

Only the news from the South Australian seat of Sturt, where Labor’s Norm Foster had been defeated, interrupted the celebratory atmosphere. “We can’t really do without Norm,” said Mrs Whitlam. “We need someone with that sort of tenacity and ferocity.” Her husband was quickly on the phone to Foster, offering commiserations and promising to find a job for him.

But Whitlam was possibly more upset by the bad result for Labor in Bendigo, and he phoned David Kennedy too. The Labor leader has what his staff describe as “a thing” about by-elections. They have played an important part in his political career. It was his role in the Dawson by-election in Queensland which saved him from expulsion over his fight with the ALP machine on State Aid in 1966. In 1967 the by-election victory in Corio in Victoria was his first triumph as party leader, and gave him the leverage to secure reforms to the structure of the federal ALP conference and executive. In the same year the Capricornia by-election success helped him to “break” Harold Holt. In 1969 a by-election in Bendigo had shown his mastery over the then prime minister, Gorton. The possibility of losing one of the seats to which he had devoted such time and effort in a by-election campaign appeared to affect him deeply.

Whitlam had been hoping McMahon would go on television first to concede. But soon after 10.30 he decided further delay would be fruitless, and prepared to return to the house and the waiting cameras and pressmen. But first he and Mrs Whitlam posed for the photographers who were gathered outside the motel room. In typical fashion, they hammed it up. “This is my best side,” said Whitlam. “Well, my nose is too big on this side,” replied his wife, “but I’ll do it for you, dear.” Their eighteen-year-old daughter turned up and gave her father a hug. “Are you happy now, Dad?” she asked. “Yes, Cathy,” he said. “I hope you are.”

Back at the house a British journalist was phoning a story to his paper in London. “Australia has a new prime minister,” he dictated. “Yes, I’m quite serious.” In the back garden the party guests were milling around the television sets, sending up loud cheers as each new set of figures confirmed the Labor victory.

The NSW ALP president, John Ducker, wandering through the crowd beer in hand, did not seem to quite believe it. “There’s no doubt, is there?” he kept asking people. “Billy McMahon’s going to lose his seat,” a gloriously drunk party worker shouted at the top of his voice. Laughter rippled from one end of the garden to the other.

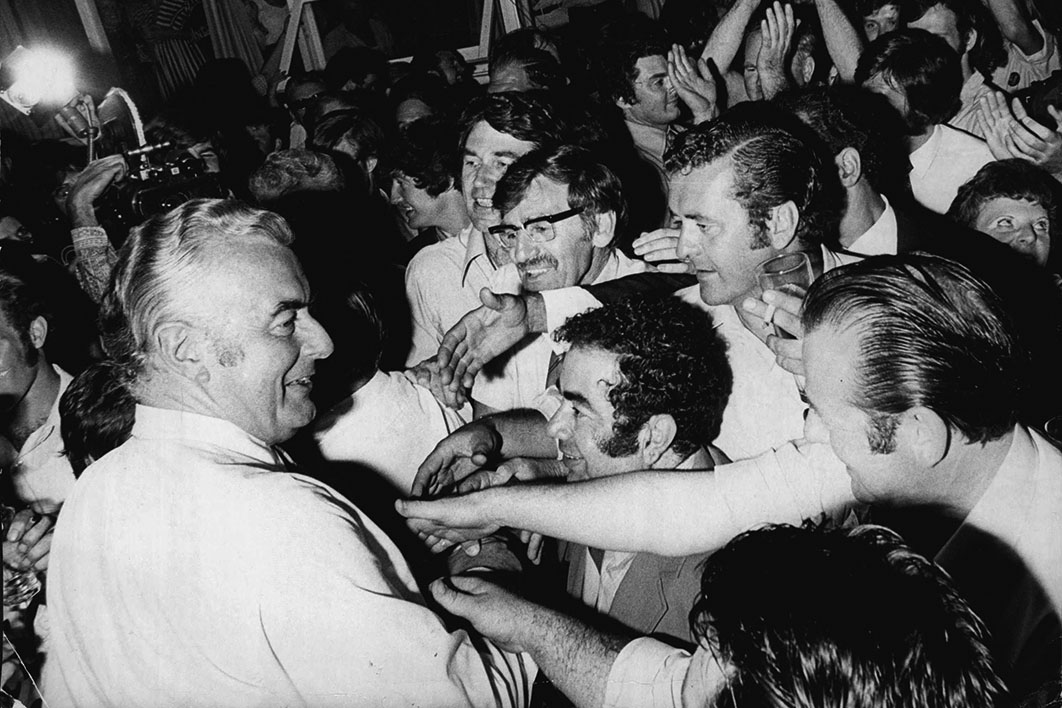

Then the word was passed excitedly through the crowd: “Gough’s coming. He’s here.” Whitlam’s tall figure could be seen slowly forcing its way through the crush as people tried to shake his hand or simply touch him.

Photographers held their cameras above their heads, trying to get shots. “Good on yer, Gough,” people shouted. And then the chanting started. “We want Gough! We want Gough!” Slowly he made his way to the sunroom door, stood there a moment smiling, and then disappeared inside.

Sometime later, when he had made his television appearance and done the right thing by his party guests, Whitlam returned to the motel and the stock of champagne for a quieter celebration. And there, away from the cameras and the crush, he was more expansive in his comments to journalists. The Liberals would have lost under any leader, he said, adding, “It’s just too silly for them to blame or for us to thank Bill McMahon. The whole show was running out of steam.” Then, a little wearily, “It’s been a long, hard road.” •

This is an extract from The Making of an Australian Prime Minister, published by Cheshire in 1973.