Most classical singers are obsessed with how beautiful they sound, how smoothly they phrase or how well-rounded a tone they produce. But the British tenor Gerald English, who has died at the age of ninety-three, could hardly have cared less. He was always after what I can best describe as a musical truth, and if he cracked a note in its pursuit, then so be it. He never played it safe.

The tenor Philip Langridge — a generation younger, and a great fan — once told me he had heard English at the Proms in Berlioz’s Requiem. He sang magnificently, Langridge said, but blew a succession of top notes. The following day, not a single review mentioned the fluffs, only the artistry.

“And quite right too!” Langridge added.

English had a remarkable career. He sang with famous conductors from Thomas Beecham to Simon Rattle (in 1976, he was the soloist in the twenty-one-year-old Rattle’s first appearance at the Proms). He sang Britten under Barbirolli (their Cologne performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings from 1966 recently appeared on CD); Vaughan Williams under Boult; Bach under Leonhardt; and Stravinsky under Ansermet and Boulez. On André Previn’s famous 1974 recording of Orff’s Carmina Burana, he sang the song of the roasting swan (was there ever a more poignant rendition?) and it became his party piece: two decades later he was still being called upon to fly to the United States to reprise these three minutes of pain for Christoph von Dohnányi and the Cleveland Orchestra.

At English’s operatic debut in 1956 he replaced Peter Pears as the devilish Quint in the English Opera Group’s production of Britten’s Turn of the Screw, the composer conducting. He sang Monteverdi at Glyndebourne, Walton’s Troilus and Cressida with Janet Baker at Covent Garden, and Berg’s Wozzeck — first as Andres, later as an especially deranged Captain — for the Paris Opéra, La Scala (several seasons in a row for Claudio Abbado), and at the 1976 Adelaide Festival in Elijah Moshinsky’s production.

Most people who heard English remarked on two qualities. First there was his purity of tone and control of vibrato. He didn’t wobble constantly as so many operatic singers do, but employed vibrato to colour certain notes. The other thing that distinguished him from nearly all his colleagues was that you could understand his words. He believed that singers with poor diction were merely being lazy. Yet in many quarters incomprehensibility is taken for granted in opera singing, and English’s clarity of diction earned him the label “character tenor.”

The other feature of his singing that set him apart from colleagues who seldom ventured much beyond the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and believed music from the 1920s to be modern, was an insatiable willingness to explore the whole musical repertory, particularly the very old and very new.

In 1950, the great countertenor Alfred Deller invited English to join his new vocal group in excavating music from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, some of which had not been sung for hundreds of years. Because there was no singing tradition — some would say bad habits — to fall back on with this music, the Deller Consort had to work out for themselves what a composer from the twelfth or fifteenth century might have wanted. Paradoxically, this same attitude equipped English for his increasingly regular forays into new music. In both cases, it was a search for musical truth.

English was fearless and could sight read anything, so he was a composer’s dream. Besides his work with Britten, he sang for Stravinsky (the title role in Oedipus Rex), Tippett (the first performance of Songs for Dov and many subsequent performances), Berio (the European premiere of Opera) and Lutosławski (Paroles tissées), each time under the composer’s own baton. He sang in the first performances of Richard Rodney Bennett’s opera The Ledge and, at Covent Garden, Hans Werner Henze’s We Come to the River, the latter in the composer’s own production.

In 1977 English established the Opera Studio at the Victorian College of the Arts and became its first director, lecturing, teaching singing, and directing and conducting operas — sometimes from the harpsichord. His presence in Australia was a boon for local composers, and among those whose works he sang early on were Peggy Glanville-Hicks, Peter Sculthorpe, Richard David Hames and Barry Conyingham.

I was particularly fortunate. I had admired English’s singing since my childhood, and he was one of the first musicians I met when I arrived in Australia from England as a young composer in 1983. We quickly hit it off, though I was very much in awe, and I summoned the courage to ask if I could compose something for him, aware that at the age of fifty-eight he was nearing the end of his career. He agreed enthusiastically, so I wrote him a song cycle to words by Christopher Reid, Sacred Places, which he sang with the Seymour Group in 1986.

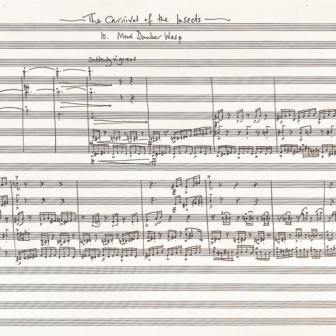

But of course he wasn’t at the end of his career. He had two more decades to go, and I had another eleven pieces to write for him: big songs and small songs, three further song cycles, an operatic role and two solo music-theatre pieces — Whispers (with Rodney Hall) and Night and Dreams: The Death of Sigmund Freud (with Margaret Morgan).

This last, which he performed at the Adelaide Festival in 2000 and at the Sydney and Melbourne Festivals the following year, was really his swansong — on stage at least — and in rehearsals, with George Whaley directing, I witnessed for the first and only time Gerry’s cheerful professionalism crack. By now we were old friends, and I was surprised to see the stress he was under.

Night and Dreams is a huge undertaking for any singer. The performer is alone on stage for more than an hour, there is no conductor to follow — because all the other sounds are prerecorded — and, in addition to singing, he is obliged to speak to the audience, in character, for quite long stretches. Gerry was pushing seventy-five and had never done anything like this. Operatic acting, yes — but this was naturalism.

The fact that he pulled it off — and triumphantly — was partly down to Whaley’s patient manner, but mostly a matter of sheer determination on Gerry’s part. A determination to get it right, as he had done for Tippett and Henze and Berio, and for all those medieval and Renaissance composers whose music he’d first sung with Deller half a century earlier.

That he was now singing my music was something I never took for granted or quite got used to. For me, working with Gerald English was always an immense privilege; but for Gerry learning new music was simply what he did. The notes were there on the page, no one had sung them before, and it was his job to search for the truth in them and convey that to an audience. And he did it so vividly, over and over. •