Michael Tippett completed his fifth and final opera, New Year, in 1988, the English composer’s own eighty-fourth year. It had its first production at Houston Grand Opera, directed by Peter Hall, the following year, with a second production (Hall again) at the 1990 Glyndebourne Festival. The latter became a shortlived touring show in Britain, and the same forces recorded it for BBC television. But that was it. New Year was neither seen nor heard for another thirty-four years.

The reasons for this are complex. Tippett lived until 1998, a few days after his ninety-third birthday. Composers habitually go out of fashion following their deaths (if they’re lucky, they come back) but in Tippett’s case the process had begun in his lifetime. This drop-off in popularity was especially marked because, in the 1970s and early 1980s, Tippett had emerged from the shadow of his compatriot Benjamin Britten to become Britain’s leading composer.

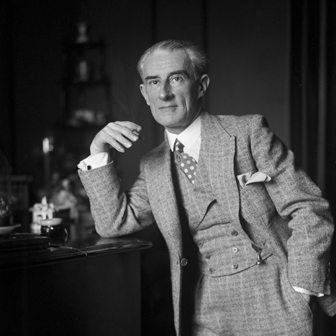

More than that, in fact: Tippett was a celebrity, swanning around the world attending — and sometimes conducting — performances of his music, receiving lucrative commissions from the likes of Solti’s Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Symphony No 4) and Houston Grand Opera, which teamed up with Glyndebourne and the BBC to pay him £100,000 for New Year (you’d have to believe most of that money was Texan). Increasingly, he cut a flamboyantly camp figure, taking his bows in yellow pirate pants and calling everyone “love.”

So what happened? Without a doubt, his music changed. But it had always changed. In 1962, at the arts festival for the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral (replacing the medieval building destroyed by the Luftwaffe), Tippett’s second opera, King Priam, was stark, angular and as much a sensation as Britten’s War Requiem, which had its premiere the following day. Certainly it was a long way from the florid lines of his first opera The Midsummer Marriage (1952).

But from around the time of that fourth symphony in 1977 there was a nagging feeling Tippett’s creativity was starting to atrophy. The rich harmonic palette and bounding contrapuntal lines of his earlier music had vanished and the hard edges of Priam had gone flabby. There was instead a preponderance of unison lines, the music was less fluent, and he seemed to be repeating himself. There was also the matter of his librettos, though that was an old story.

Planning his choral work A Child of Our Time in the late 1930s, Tippett had taken a draft to T.S. Eliot, hoping the poet might agree to collaborate. Eliot looked over what the composer had written then told him to complete the job himself, since anything Eliot contributed would be so much better it would stick out a mile. For the rest of his life, Tippett used this story as justification for writing his own words, and when we read those words on the page it’s hard not to see Eliot’s point.

From the start, Tippett’s librettos were sparked by a kind of woolly Jungian mysticism and peppered with clichés. As he got older, spending most of his leisure time in front of the television, the clichés came thicker and faster and included American slang, much of it out of date by the time of his operas’ performances. He made no secret of his love of cop shows like Starsky & Hutch; the police “Lieutenant” in Tippett’s fourth opera, The Ice Break (1977), might as well be Theo Kojak. New Year betrays Tippett’s enthusiasm for Blake’s 7 and The Flipside of Dominick Hide, the composer happily confirming these influences. As Oliver Soden points out in his illuminating essay with the new recording, each of the opera’s three acts begins with the same brief “overture,” as though they are episodes in a TV series.

Set in “Somewhere and Today,” New Year concerns two orphans, Jo Ann and Donny, and their foster mother, Nan. Jo Ann is a trainee doctor who would like to help the orphans of “the terror town” but is agoraphobic. Donny, a delinquent, is part of the town’s problem. Jo Ann’s unhappiness comes to the attention of three time-travellers from “Nowhere and Tomorrow” who arrive in their space ship on New Year’s Eve. The overriding theme of the piece is that love trumps science.

Much of the criticism of the opera centred on its sci-fi subject (as though opera plots ought to be inherently believable), the libretto (a by-now traditional criticism), the tendency for the singers to lapse into speech for no very good reason, and the jangly sound of an orchestra with two electric guitars, three saxophones and a great deal of percussion. But there was also the figure of Donny, who is Black, his origins deliberately vague — Donny himself is ignorant of them. He goads Jo Ann, indulges in a lot of cod-Caribbean talk and quasi rap, plays with racial stereotypes and, in an attempt to find out who he is and where he’s from, imagines himself a jungle animal. As a portrait of a teenage boy ripped from his culture and psychologically scarred by the alienation, it’s believable. But you certainly wouldn’t go there today and even at the time it raised eyebrows.

The new recording from NMC doesn’t hold back — what would be the point? Ross Ramgobbin’s performance as Donny is visceral and the singers of the other roles are no less committed. Under the baton of Martyn Brabbins, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers make the best possible case for this undoubtedly problematic piece. As I listened all the way through for the second time I found myself falling under its spell.

This is real Tippett even if, in places, it’s thin. The opera’s subject matter is typical of his humanity and there are many echoes of his earlier work. The whole idea of the piece might be thought of as a reimagining of The Midsummer Marriage — Midsummer’s Day replaced by New Year’s Eve, ancients by aliens — and there are numerous small references throughout to that first opera. A Child Our Time is present, too. When the denizens of “terror town” turn on Donny and make him their scapegoat, it’s hard not to think of Herschel Grynszpan, whose shooting of a German official the Nazis made their excuse for launching Kristallnacht, and whose story inspired Tippett’s wartime oratorio.

But it’s the music itself that will remind any Tippett fans of the glories that preceded New Year. The ecstatic quartet in Act 2 suggests the great finale of A Child of Our Time, and the intertwined lyricism of Jo Ann and the time-travelling Pelegrin is almost a match for that of Jenifer and Mark in The Midsummer Marriage.

And then there’s “Auld lang Syne,” sung by the chorus at the end of the second act. Tippett often made use of other music — the American spirituals of A Child of Our Time, the Beethoven quotes in the third symphony and fourth string quartet, “We Shall Overcome” creeping into The Knot Garden. Here, at the stroke of midnight, “Auld Lang Syne” is underpinned by the tolling of a low gong (out of time) and decorated by furious roulades from the upper strings. It’s quintessential Tippett, that mixture of darkness and light, hope amid turmoil.

Often when I listen to Tippett’s music, I think of words he spoke in 1971 for a BBC television documentary, “Poets in a Barren Age.” I thought of them again as I listened to New Year. Composing, he said, was an “age-old tradition” involving the creation of “images from the depths of the imagination… Images of vigour for a decadent period, images of calm for one too violent. Images of reconciliation for worlds torn by division. And in an age of mediocrity and shattered dreams, images of abounding, generous, exuberant beauty.” •