THE parking attendant near my office is a pleasant thirty-two-year-old Kenyan man called Timothy Angaluki. Like many workers in Nairobi, his family lives “up country,” which in his case means Kitale, a Rift Valley town around 325 kilometres to the northwest of Nairobi, close to the border with Uganda.

Until a few years ago, Timothy could only speak to his wife every couple of weeks when they were both near a public phone. He sent part of his salary home each month through the post office, and if nothing went wrong she could pick it up at her local branch three or four days later, minus a hefty commission. Timothy was barely aware of the internet, having never had the opportunity to use a computer. News came from the radio, or a discarded copy of yesterday’s newspaper.

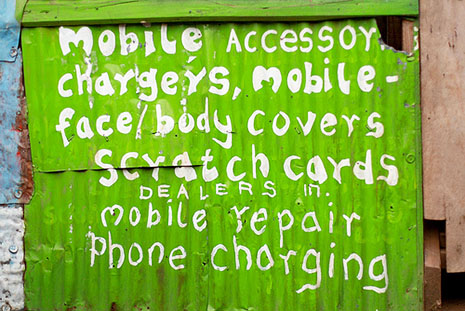

Then things started to change. Timothy had saved enough money to buy a secondhand mobile phone, and one for his wife. At first, they didn’t talk or text much, unless there was an emergency. “The phone was good,” he says, “but we couldn’t afford to speak much at that time because calls were so expensive.”

And there was still the problem of sending money home. As someone with a regular job, even a low-paid one, he was responsible for raising cash for hospital bills or funeral costs if something happened in the wider family. The four days it took to transfer money was often too long.

But then Timothy’s mobile service provider, Safaricom, introduced a new service called M-Pesa, or mobile money. Not only does it allow people to store cash on their phones, but they can also send it instantly and cheaply to anyone else on the network simply by sending a text message. Last week Timothy sent 4000 Kenyan shillings (A$45) to his wife, who walked to the nearest M-Pesa agent, showed them the text message and withdrew the cash within an hour or two.

Timothy showed me his phone, a simple flip-open model from Samsung. It has a small screen, but is web-enabled. For the first time in his life, Timothy has started using the internet. Most days he reads the local news headlines and checks the sports scores. “Chelsea, Manchester United, to see how they are doing,” he tells me, grinning.

Working as a journalist in East Africa I sometimes feel that the pace of change is very slow. Countries appear to open up politically, then close up again – as has happened, most recently, in Ethiopia, Uganda and Rwanda. Year after year Somalia maintains its status as the world’s most ungovernable nation (though the most successful in terms of piracy at sea). But at an individual level things have changed – largely thanks to the mobile phone, which, as Timothy’s story suggests, is no longer just a talking device, but a wallet and a news browser and a social networking tool.

The pace of change and the level of innovation have been extraordinary. At the start of 2000 there were not many more than 15,000 mobiles in Kenya. Since then Safaricom, the country’s biggest mobile service provider, has sold more than twelve million SIM cards – almost one for every three Kenyans. The vast majority of their customers would never have had a fixed-line phone – and now will probably never need one.

Similarly, most users of M-Pesa, including Timothy, have never been able to open a bank account, since they were not considered as paying propositions by the major financial institutions. (The highly profitable Equity Bank has proved that assumption wrong by targeting a mass customer base.) More than US$1 billion is expected to pass through M-Pesa in Kenya this year. In conjunction with money transfer giant Western Union, Safaricom has also made it possible for people in forty-five countries and territories to send cash directly to a Kenyan subscriber’s mobile, tapping into the huge market for international remittances.

Safaricom, which is listed in Kenya and part-owned by Vodafone, has been hugely successful. Good service and smart products played a part, but so too did the lack of competition in the early days. For a long time its only rival was Celtel (now owned by the Indian company Airtel and branded as such), and both companies were able to charge high tariffs. When I arrived in Kenya in 2004, my monthly Safaricom bill, including roaming, often topped 50,000 shillings (A$570). But today there are four mobile operators, with France’s Orange and India’s Essar joining the sector and launching their own money transfer services, as Airtel had done earlier.

The competition is cut-throat, especially in the calls market. In the space of a few weeks last year, prices were cut by up to 80 per cent after Airtel slashed its charges, forcing its competitors to do the same. My own phone bill is now usually less than 10,000 shillings (A$115). I’ve even noticed that the number of people “flashing” me – where a caller lets the phone ring once before hanging up, expecting you to call back – has gone down. Prices are so low – typically around three Australian cents per minute – that people don’t bother trying to save the cost of a call.

Indeed, the mobile providers are now turning a larger part of their attention to their internet business, which have received a huge boost in the last eighteen months as three under-sea fibre-optic cables landed in Kenya. Surfing speeds have surged. True broadband has finally arrived.

At the same time, smartphones are getting ever cheaper – a Huawei Android handset goes for just over A$100 here. While that’s out of Timothy Angaluki’s reach, it isn’t too expensive for members of Kenya’s ever-expanding middle class, who have already shown a fondness for BlackBerrys and iPhones as well as cheaper mass-market smartphones from Nokia and Samsung.

The potential of this consumer base has been recognised far beyond Africa. Facebook has made surfing its mobile site almost free in several African countries to boost its clientele, picking up most of the bill for the data charges. Google has been expanding its offices in South Africa, Kenya and Ghana. After just a few years, millions of Kenyans – and Africans in general – can now tap into a seemingly infinite and instant world of information for the first time simply by reaching into their pockets. The effects of this, whether they’re political (as with the role of mobile phones and social media in the North African revolutions), social or economic, will all be felt in the years to come.

But for now, people like Timothy – and me – are simply appreciating the benefits. •