If I could have visited Mary Gilmore at her home in King’s Cross, Sydney, I wonder what she would have made of me? This meeting could never have occurred — Gilmore died in 1962, aged ninety-seven — but still I imagine myself mounting the stairs to her first floor flat at 99 Darlinghurst Road, where she had lived since 1933, and nervously knocking at her door.

The great writer has spent the morning making jam, and the flat is still heavy with the scent. A little jar is set aside for me to take home. Dame Mary likes making jam, but as she escorts me in she’s quick to notice that any talk about the ratio of fruit to sugar is wasted on me. I’ve never had time to make jam.

My hostess sets about making yerba maté tea for me, chatting about how she grew to like it during her years in South America. She had travelled to Paraguay in 1896 to join the utopian socialist settlement known as Cosme, where she met and married her Australian husband Will Gilmore, and after the failure of the settlement in 1900 had moved to Argentina with Will and their baby son Billy while Will worked to pay for their passage home.

Forty years later the Australian magazine Pix published a feature on Mary Gilmore, who was famous by then as a journalist, poet and social reformer, and photographed her at home drinking yerba maté the traditional way from a gourd, using a straw known as a bombilla. Today, though, she presents it to me from a teapot. I was expecting a bitter, grassy concoction but it turned out to be quite mild and pleasant. The critical thing, Dame Mary tells me as we settle down in her cluttered living room, is to brew it gently in water that is hot but not boiling.

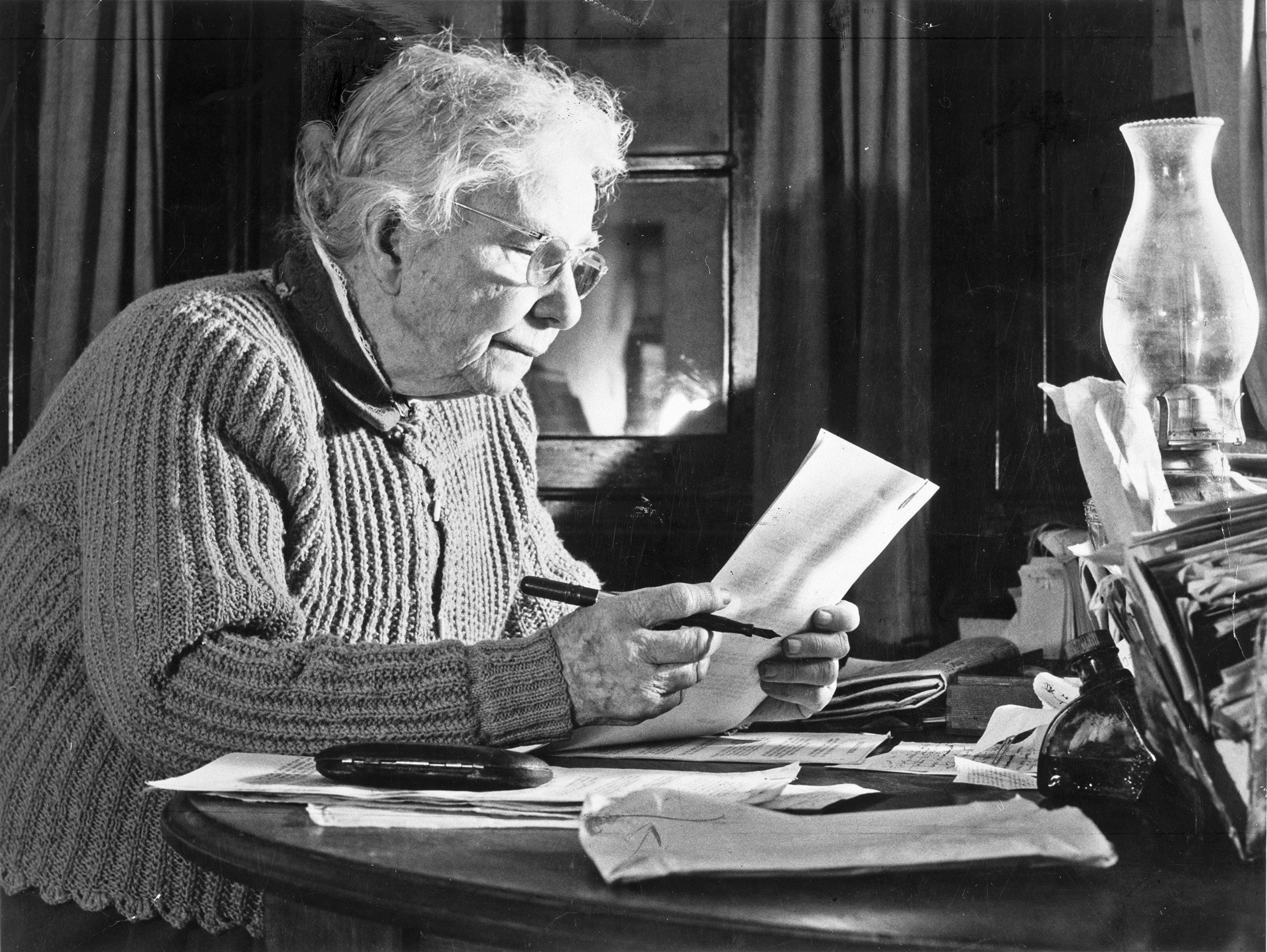

When journalist Leslie Rees visited Mary Gilmore at home in 1936 his impression of her was of “living eyes, richly, deeply brown as the eyes of William Butler Yeats, in a face that shows the scars of a life faced with dignity and intelligence.” Her brain was “as active and unsentimental as an electrical coil.” Bright and lively conversation was said to be the essence of life to Mary Gilmore, and that’s partly why I’m nervous; I’m not a sparkling conversationalist myself. So it’s a relief when the heavily underlined copies of Soviet Weekly are set aside and she waits with a kindly look for me to broach the subject I’d come to talk about.

I ask her about the years she spent editing the women’s page of the Australian Workers’ Union paper, the Worker. I tell her I’m especially interested in the first pages she edited, published in January 1908, in which she put a call out to women to write to her on any subject that interested them and to share their knowledge, even just little labour-saving procedures in the kitchen, with other readers. Her hope was to get at the “needs, the hopes and fears and desires” of all women, in a “bond of unity” from one end of the country to another.

Ah yes, she muses. She had wondered how to educate women about how politics and current events could affect their lives. But how do you reach the tired woman rocking the baby’s cradle with her foot while she peels potatoes or darns stockings in her lap? Such a woman, Dame Mary chuckles, has no time to read the prime minister on tariff reform.

“So, women did write to you?”

“Oh my word yes! About all sorts of things, very personal sometimes. Distressing. And the questions I got! From men as well. People seemed to think I was a one-person encyclopedia. Has the price of calico gone down? How do you make soap? How do you get rid of fleas? Once I even published a poem about my weekly mailbag.”

“Yes, I’ve read that.”

“Have you indeed!” She pauses. “So why are you here?”

“Do you still have the letters women wrote to you?”

Dame Mary stares.

“No. Why should I keep them? I dealt with them and threw them in the wastepaper basket.”

I think of all that history consigned to oblivion.

“Look around you. I don’t have space to keep that kind of thing. Do you know how many times I had to move house in those years?”

“No.”

“Actually, nor do I any more. But it was a lot.”

“I wanted to see the originals of the letters.”

“Why? They weren’t written to you.”

She leans forward.

“What exactly you are searching for?”

What indeed? What was it that brought me in my imagination as a suppliant to Mary Gilmore’s door?

I had become interested in Gilmore’s editorship of the Worker women’s page because out of it emerged one of Australia’s most successful community cookbooks. The recipes and household hints section had been so popular that she compiled the contributions into a book, The Worker Cookbook, published by the paper in 1914. It went through ten editions between then and 1919.

A trail through secondary sources led me to Gilmore’s papers at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, where apparently there were letters from women who had written to her in response to the cookbook. They survived because the frugally minded poet had used the backs of them as scrap paper to draft her poems.

With archives you never know what will get, I know that perfectly well, but still I dreamed of a feast of untapped primary source material. The cookbook would provide the necessary narrative focus for a kitchen-window glimpse into the domestic lives of working-class women more than a hundred years ago. The archival material would be exactly as I imagined it would be, and the result would be awesome.

Not. The trail turned out to be false, at least as far as the cookbook was concerned. There are letters from readers within files of Gilmore’s drafts of published and unpublished poems. I found about eighty, in MS 727 series one, two, three and nine, and in MS 8766 box two. Unfortunately, they can’t be identified from the library’s finding aids because the archivist who described the records didn’t think them important enough to note.

Only a handful of the letters refer to the cookbook, and then just in passing. The handwritten drafts of poems were often illegible (although as Gilmore might say, they weren’t written for me) and the reverses were usually blank. My project on The Worker Cook Book collapsed before my eyes.

I wasn’t going to give up; I’d stay for whatever I could find. I must have turned over thousands of handwritten and typed sheets. On and on, turning, turning, rocking myself mentally to sleep in the peaceful hush of the library reading room.

Suddenly, this: “… a worm will turn. When we think of all the suffering that is all over the world and for what purpose, it seems for one class only and it is time the working class woke up and got their rights.”

I was wide awake now too. Who was this? Mrs E. Birch, whoever she was. I only had the second page of her letter, no address and no date. She has been reading the Worker for two years, she says, and finds it appeals to her “way of thinking.” She and her husband were on an “estate” as a married couple, but to live and save from a man’s weekly wage was “impossible.”

More turning. Maud Woodbury from Cessnock wrote in 1918 to ask Gilmore to send a word of friendship and cheer to some “lonely sister” of the “never-never country.” She enclosed a second letter for Gilmore to forward to anyone she knew who might appreciate it. “Those brave, quiet women of the glorious proletariat always fill me with deepest admiration and sympathy.”

A mother wrote a frantic account of her baby’s illness, but I only had the second page of her letter. A doctor had advised her to stop breastfeeding and give the baby whey, but she refused. “I gave her castor oil and looked to my own health.” The baby was weaned eventually on to Glaxo (a baby formula) but “one tin nearly killed her.” She tried barley water and Nestlé’s Milk Food. The baby developed a fever and gastritis. There was a hospital visit. Nearly at the bottom of the page now. Barley water again, and white of egg, and brandy. “I gave her…” — and there it ends.

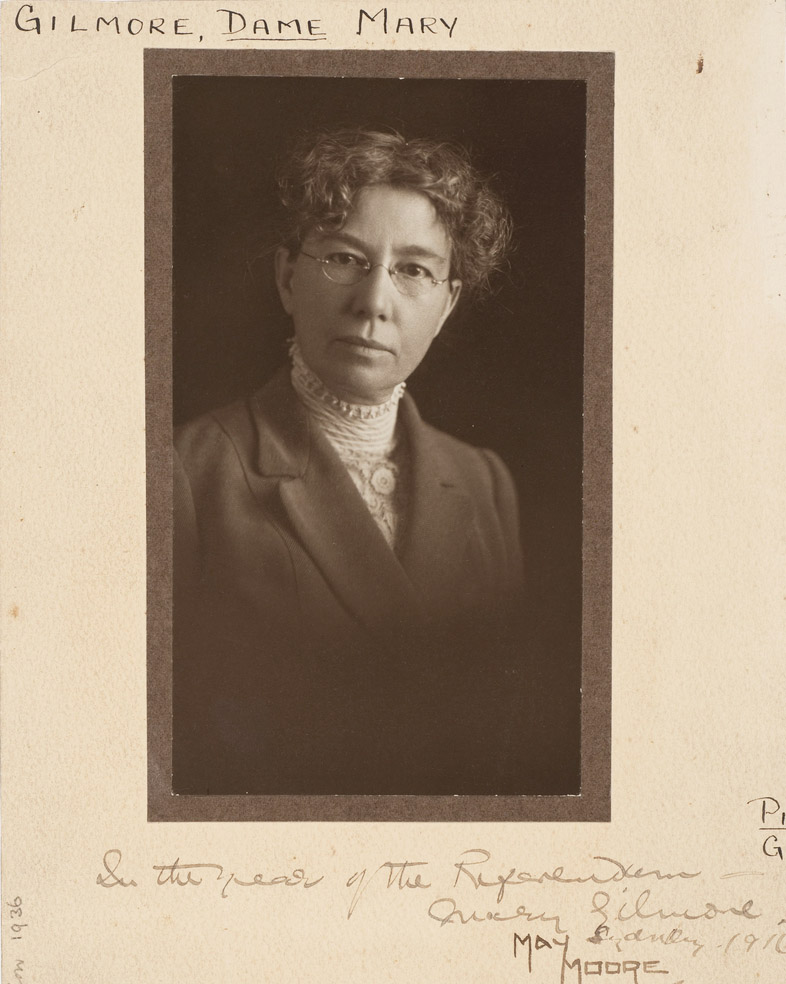

Mary Gilmore photographed by May Moore in 1916, during Gilmore’s time at the Worker. State Library of New South Wales

A mother of six wrote in 1920 from Woolbrook, south of Armidale, to ask how to find a book on midwifery because she was anxious to help pregnant women in her town with their births, there being no doctor or nurse for sixteen miles. She had written to the state government and been told that such a book would not be suitable for “inexperienced women.”

May Kent from East Moree wrote in 1920 about an elderly woman living alone next door who, because of a horror of being buried a “pauper,” had “done without many a little thing to put a couple of shillings away.” This woman had been told that if it was discovered that she had money in the bank it would interfere with her pension. Could Mrs Gilmore advise on this point?

I found many of those much smaller questions that obviously caused Gilmore so much amused exasperation. J.M. Mann from Wyalong wanted information on how to rear young parrots — blue bonnets and “bullan bullans” (ringnecks) — because oatmeal failed and his birds died. Jessie English from South Gippsland wanted to know if the Australian School of Sketching in Sydney was a genuine establishment or a “swindle.” George Ritter from Narabri had “scurf” in his hair and sickness in his fowls.

Then there were the letters from children. Every week Gilmore published a selection of these and, perhaps recalling her own childhood, tended to favour those from children in remote places. Joyce Jones from Pine Ridge in northern New South Wales wrote in 1918: “I am nearly twelve years old and would like some girls to write to me we have three cats and three cows and I am very fond of reading my Uncle takes the worker we live almost on the bank of the Marra Creek.”

I was charmed to discover letters from two sisters, written on successive days in October 1917, asking to be put in touch with pen-friends. Lilly and Annie Hasted wrote from Listowel Downs via Blackall, south of Barcaldine in Queensland. Both remarked on their faraway home. “It is very lonely out here,” wrote Annie, aged twelve.

Sometimes all I found was a torn fragment. “Well Mrs Gilmore,” wrote someone from Burrandong via Mumbil in 1919, “after reading those pitiful letters in the Worker about tired Mothers I think it is something terriable my mother is only a poor woman and we have to battle through the world as good as we can there are…” — and the rest of the sheet is torn off.

Most perplexing of all was a sheet torn vertically rather than horizontally, leaving only the right-hand side of the page. The letter was from a child, apparently a regular correspondent, along with her sister, to the Worker. Since her last letter there had been a flood at their place, she says, and she is knitting a sock. Here I did study what Gilmore had written on the other side, a lullaby. I wondered if the narrow width of the sheet had helped Gilmore to keep the lines short as she drafted the poem. Here are the first two verses.

Here we go

Sleepy slow

Rockabye baby

Bye OStill little foot

Still little hand

Hushabye baby

Bye O

Gilmore’s women’s page was much more than an advice column. Typically each page carried several leading articles written by Gilmore herself in which she explored her many cherished causes. These could include the need to introduce an aged pension; the plight of rural women living in poverty; poor treatment of female servants and prisoners; the introduction of maternity allowances, child endowment, and pre- and post-natal care for mothers; and women’s rights to living wages and equal opportunities, and indeed to the same rights as men to freedom, independence and happiness.

Readers’ letters were nevertheless critical in informing Gilmore’s advocacy on these and other issues. In her twenty-three years editing the page, Gilmore must have read thousands of letters from readers, especially women. They might be published in full, or their content arranged into copy that Gilmore would write, often with added commentary of her own.

Now that the Worker (known from 1913 onwards as the Australian Worker) is fully digitised and available via the National Library’s Trove website, this vast corpus of Gilmore’s work is fully searchable. This makes it possible for me to discover if the readers’ letters I saw in Gilmore’s papers were published or mentioned, but of the selection noted above I could only trace the letters from Joyce Jones, the Hasted sisters, and the man rearing parrots. Of the rest, nothing. So I can’t say whether the sick baby survived or the woman from Woolbrook received her midwifery book or the caring woman received advice for her pensioner neighbour.

But the correspondent who mentioned tired mothers was responding to a regular theme on the Worker’s page. In 1914 Gilmore published some poems (not her own) titled “Tired Mothers,” which initiated a stream of letters well into the 1920s. Women wrote that they were exhausted with childrearing and housework and the strain of feeding their children on their husbands’ small wages. Of how sad it made them that their children could rarely eat fruit and vegetables except potatoes or receive a new toy at Christmas. That they would rather die themselves than bring any more children into the world.

Reflecting in 1919, Gilmore wrote that she was proud to have published as many of these letters as she could because, she claimed, no women’s column in any other paper was bothering. “They come to me by every mail. The saddest things can never be published; they are too individual and too private — and sometimes too terrible.”

Gilmore had always been unusually sensitive to the suffering of other people and had known loneliness herself. Life as a bush wife on the Gilmore family farm in Victoria was unbearable for her and in 1911 she and Will decided to live apart. Their adored son Billy went with Mary to Sydney, but as soon as he was old enough he joined his father working properties in Queensland. Mary and Will still regarded themselves as a couple but the family was seldom together.

So although she relished her independent existence in Sydney as a celebrated poet and journalist, Gilmore missed the intimacy of a small family circle. Torn as she was between love, duty, work and family, the struggles of other people never failed to move her, and her own warm and compassionate manner was very evident to readers.

Relations between Gilmore and the management of the Worker deteriorated throughout the 1920s and in February 1931 she resigned. In a long, angry letter to the president of the Australian Workers’ Union, John Barnes, she declared that in addition to her published work for the paper, there had been considerable extra labour — unpaid and unthanked — privately answering letters from thousands of “poor souls” who had had no one else to turn to.

Drunken husbands, persecuting policemen, unwanted babies, family maintenance, workers’ compensation, pensions: she dealt with them all. “From New Zealand to Tasmania, from Sydney to Port Darwin, you will find letters of mine in every direction.” And they had not cost the union even the postage stamp that carried them.

A diagonal line across each of the readers’ letters I saw in her papers suggests that Gilmore had dealt with them, if not by publication then by private reply. This gets me imagining the arrival into thousands of homes of a letter from that much-loved author, Mary Gilmore. Many a woman must have quietly slipped one into her apron pocket to study later, anxiously, by the fire, when the family was asleep.

I don’t consider Gilmore an “agony aunt” in the modern sense because, in print at least, she mainly focused on responses to practical problems. In those less explicit times, her readers’ emotional and sexual difficulties were probably among the things she believed “too terrible” to publish.

They are gone, most of them, those readers’ letters to Mary Gilmore, and her private replies are also scattered and lost. Yes, her journalism for the Worker does incorporate many of them in one form or another, and yes, digitisation opens up research pathways undreamed of in an analogue age. Why chase what is not there to be found?

Sometimes I think of a line from Tennyson’s Ulysses (one of my father’s favourite poems): “Tho’ much is taken, much abides.” It offers a helpful path towards acceptance, at least in some circumstances. But in archives the reverse can apply: much abides but much has been taken. That absence is not nothing; it leaves a trace. The letters and letter fragments I found at the National Library pointed so powerfully to what was not there that for a while all I could do was sit there, rigid with disappointment.

Still, within that absence there was also an encounter with aspects of myself, my desire to gather up what is lost, mend what is broken, and bear witness to the uniqueness of every human experience.

“There is something I can show you though.”

“Oh yes?”

“On the table over there, that little card. Bring it here.”

She turns it over in her old fingers. On the front is an illustration of a kitten with a blue bow around its neck holding a bunch of flowers.

“I was on television, you know.”

“Yes, I saw it. I can’t believe they brought all their cameras and things in here.”

“So tiring.” But she is smiling.

She hands me the card. It’s from a ten-year-old girl, Christine Higgs of East Maitland. Christine had carefully dated it 12 June 1959. She wrote to say that she had seen the telecast from Dame Mary’s flat.

“I enjoyed it. I heard your poems, and I also saw your kettle boiling.”

On the back of the card she had written out a poem of Dame Mary’s she had learned at school.

“Read it for me.”

The Fairy Man

It was, it was a fairy man

Who came to town today.

‘I’ll make a cake for sixpence,

If you will pay, will pay.’He iced it with a moonbeam

And found a penny, too;

He made a cake of rainbows,

And baked it in the dew.

“I read that one at school too. But I think Christine has muddled the lines a bit…”

I look up. Dame Mary is asleep. •