In my part of the world, fewer and fewer people seem to remember Arthur Stace. Younger friends and colleagues will frown awkwardly at the mention of someone they think they should know about but really don’t. “The Eternity man,” I prompt. That bloke who wrote the word “Eternity” in chalk thousands of times on Sydney footpaths. Remember when “Eternity” was illuminated on the Sydney Harbour Bridge on 1 January 2000?

Perhaps it’s understandable: this is a Sydney story, and I live in Canberra. In Sydney his memory still seems strong — although, since Stace died in 1967, fewer people will remember having discovered an “Eternity” inscribed by the man himself in his famous elaborate copperplate. It would be even rarer to find someone who actually glimpsed him at work in the pre-dawn, head bowed, kneeling to leave his one-word message in chalk or crayon.

I became curious about Stace during trips to Sydney in the 1990s, when a highlight was to call in at the Remo store in Darlinghurst to browse all manner of cool stuff you probably didn’t need but was fun to own, including t-shirts, prints and other merch emblazoned with Stace’s “Eternity” in a design by artist Martin Sharp.

Sharp had been incorporating Stace’s “Eternity” into his work for years, and a five-metre rendition on canvas adorned Remo’s Crown Street window — stopping traffic, according to proprietor Remo Giuffré. From beyond the grave, Stace was very good to Remo. “We were never ones to miss a good merchandising opportunity,” he recalled.

Arthur Stace posing for photographer Trevor Dallen on 3 July 1963. Sydney Morning Herald

Stace’s fame peaked in the 1990s, but Sydney had always been fascinated by him. From the 1930s onwards the discovery of an “Eternity” on pavement or wall was a unique and unifying experience for Sydney residents. Graffiti was still uncommon, and the letters were so perfectly formed, the meaning so tantalising. Who was this Eternity man? No one knew.

By the 1950s there were so many rumours, so much press speculation, and increasing numbers of false claims by impostors that in 1956 Stace allowed his identity to be revealed. By 1965 he estimated he had written “Eternity” 500,000 times all over Sydney.

Stace’s story, as he told it, was that he was born into poverty. His parents, two brothers and two sisters (actually he had three sisters) were all alcoholics, he said, and he himself was a drifter, a petty criminal and an alcoholic for decades before he converted to Christianity. That happened after he joined, by chance, a service in August 1930 at St Barnabas’s Anglican Church, Broadway, on the promise of tea and cake afterwards. The preacher was the Reverend R.B.S. Hammond, famous in Sydney as a “mender of broken men” — men like Arthur Stace who believed themselves beyond help. Years later Stace was fond of saying that he went in for rock cake and came out with “the Rock of Ages.”

He gave up alcohol and was befriended by Hammond, who gave him a job at the Hammond Hotel, a hostel he ran in Chippendale. Stace worked in its emergency depot helping men in need of a wash and a shave, or repairs to their clothes and boots.

Spiritually, though, Stace was more drawn to the services at the Burton Street Tabernacle, a Baptist church in Darlinghurst. There, in 1932, he heard a sermon by a famous evangelical preacher of the day, John Ridley. “Eternity! Eternity!” Ridley cried. “I wish I could sound, or shout, that word to everyone in the streets of Sydney. Eternity! You have got to meet it. Where will you spend eternity?”

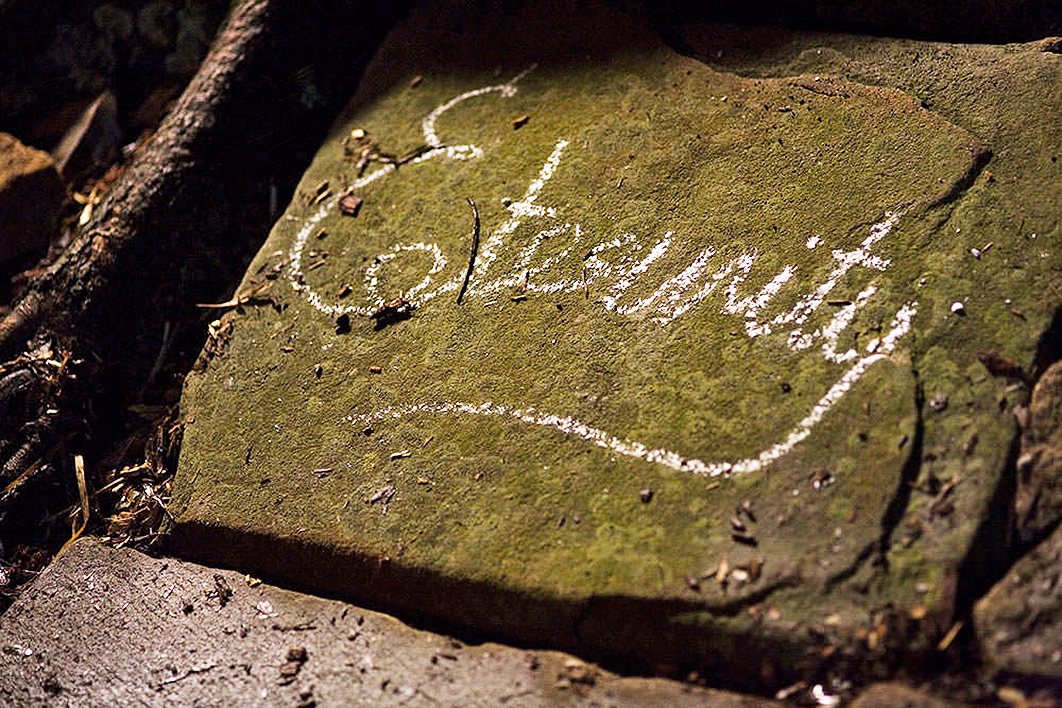

Stace was profoundly moved. Leaving the church, he discovered a piece of chalk in his pocket and bent down and wrote “Eternity” there and then on the ground. He joined the community at Burton Street, and that was the beginning of his new life as a reformed alcoholic and self-described “missioner” seeking to convert others.

Arthur Stace (seated) as emergency depot manager at the Hammond Hotel in the 1930s. Courtesy of HammondCare

When an energetic new pastor, Lisle Thompson, arrived at Burton Street in 1951 the two men immediately became friends. One day, after an outdoor service, Thompson spotted Stace at work with his chalk: “So you’re Mr Eternity, Arthur,” he queried. “Guilty, your honour” was the reply. Thompson wanted to share Stace’s story and eventually he persuaded Stace that an account of his conversion, written as a “tract,” would be a good evangelistic tool, an exemplar for others. Titled The Crooked Made Straight, Thompson’s eight-page account briefly noted that Stace was the Eternity man. “This one-word sermon has challenged thousands and thousands,” he added.

The tract circulating quietly among churches was not enough for Thompson, and finally Stace let him take “Mr Eternity” to the press. The scoop went to Tom Farrell at the Daily Telegraph and the story covered six columns in the Sunday edition on 24 June 1956. The mystery was solved, and overnight Arthur Stace, living modestly in Pyrmont with his wife Pearl (they met through church activities and married in 1942), became one of Sydney’s most famous citizens.

In the ensuing years Stace was happy to grant a further press interview now and then. In 1965, two years before his death, he told a journalist that he had tried a few different slogans — “Obey God” for instance — but that “I think eternity gets the message across, makes people stop and think.” It certainly did, but what Stace might not have realised was that with increasing material prosperity, secularism and multiculturalism in Australia, younger people were becoming baffled.

Martin Sharp first spotted an “Eternity” in 1953 when he was just eleven, and was captivated. “What does it mean? Why is it there? Who wrote it?” He didn’t learn the full story of Arthur Stace until 1983 when he was given a copy of Keith Dunstan’s book Ratbags, published in 1979. Along with Percy Grainger, Barry Humphries, Frank Thring and others of that ilk, Arthur Stace was one of Dunstan’s “ratbags.”

In 1958 journalist Gavin Souter had compared Stace to bohemian rebel Bea Miles and other Sydney “characters,” including a man who sat perfectly still on a bench in Hyde Park with an open packet of peanuts in his lap, covered head to foot in pigeons. In 2001 Peter Carey declared that Sydney didn’t love Stace because he was “saved” but because he was “a drunk, a ratbag, an outcast… a slave to no one on this earth.” Clive James in 2003 simply called him a “lonely madman.”

Christians, on the other hand, had little difficulty in interpreting Stace’s message the way he meant it — that there is a life after this one and we need to be prepared for it. For them there was nothing peculiar about a devout Christian wanting to spread such a message. In 1994 the Reverend Bernard Judd, an Anglican rector and long-time friend of Stace, declared emphatically in a filmed interview that Arthur was not a fanatic, not obsessed, and rejected the association with Sydney’s eccentrics. Stace was “a thoroughgoing reasonable rational Christian.”

When a full biography of Stace, Mr Eternity: The Story of Arthur Stace, appeared in 2017 it was published by the Bible Society. The avowedly Christian co-authors, Roy Williams and Elizabeth Meyers (the latter a daughter of Stace’s friend Lisle Thompson), reiterated Judd’s assessment to again counter the idea that Stace was a “weirdo,” or mentally ill. He was unusual, they conceded, but that could be said of any “prodigious achiever” in human history.

Poet Douglas Stewart could embrace the sublime and transcendent in Stace while avoiding the preachy context, and in so doing helped propel Stace’s work into our modern, secular age. The oft-quoted first stanza of his poem “Arthur Stace,” first published in 1969, runs thus:

That shy mysterious poet Arthur Stace

Whose work was just one single mighty word

Walked in the utmost depths of time and space

And there his word was spoken and he heard

Eternity, Eternity, it banged him like a bell

Dulcet from heaven sounding, sombre from hell.

Stewart’s poem helped inspire Lawrence Johnston’s documentary film Eternity in 1994. Parts of the poem are read during the film, and its beautiful cinematography encompassed a similar sense of light, shadow and mystery. The soundtrack was adapted from Ross Edwards’s haunting orchestral work Symphony Da pacem Domine.

Like Stewart, Johnston wanted to explore Stace’s part in the biography of Sydney, and black-and-white recreations feature an actor (Les Foxcroft) as a silent, lonely, Stace-figure in an overcoat and felt hat, head bowed, walking, kneeling and chalking. An assembly of people, including Bernard Judd, Martin Sharp and artist George Gittoes, describe how Stace had inspired or influenced them.

Gittoes was one of few to have witnessed Stace at work. He had been staring idly into a shop window early one morning in 1964 when he became aware of the image of a man reflected from across the street. As he watched, silently, unwilling to interrupt, the man knelt “almost as if in prayer” and wrote something on the ground. Gittoes had never heard of Arthur Stace then and thought that “Eternity” had been written just for him. As a fifteen-year-old boy “looking for signs,” he said, that one word seemed to be “like a whole book of words,” and the experience had remained “like a tattoo on [his] soul” ever since.

There was something else that struck the artist’s eye, and he remembered it even after thirty years: Stace’s shoes were too big. As the man knelt, Gittoes could see clearly into the gap between his sock and his shoe.

I too am fascinated by this detail. Everyone remembers Stace as a carefully dressed man, always in a suit, tie and felt hat, and an overcoat for winter. The few photographs of him attest to this. But Gittoes noticed that his shoes were much too big, clearly not originally his own. This could have been because as a small man, only five foot three, Stace had trouble finding shoes to fit. Or because even in the relative comfort of his later years Stace was still too frugal to buy new shoes. Whatever the case, my imagination gets to work in that gap between the actual man and how he presented himself to the world.

Stace’s adeptness at controlling his own story for public consumption leads me to wonder: what was in the gap? What would drive someone to write “Eternity” on the footpath every day for thirty-seven years? Half a million times. Was Stace “unusual”? Obviously. A “madman”? Unhelpful. “Obsessed”? Yes, I think so.

Stace was always a poor man, but the dimensions and impact of that poverty have until recently been under-appreciated. The trauma that would afflict his life began even before he was born. His biographers have shown that his mother, Laura Lewis, had two children with an unknown father, or fathers, while she was a teenager living at home with her parents in Windsor, New South Wales. The first baby died, and the second, Clara, born in 1876, nearly did too.

One day Laura left the three-month-old with her own mother, Margaret Lewis, while she visited a neighbour. Ten minutes later Laura was called home to find Clara pitifully unwell. Margaret claimed to have given her granddaughter a drink of tea, but a doctor was called and, as he later testified, found the baby suffering from “gastric irritation of the stomach and bowels,” retching and crying incessantly. Soon it was discovered that what Margaret had actually given Clara was carbolic acid, a common disinfectant. A local chemist confirmed that he had sold it, diluted in oil, to Laura during her pregnancy to treat an abscess.

Remarkably, Clara survived, and although Margaret appeared before a magistrate, a murder charge seems to have been dropped. Why? If Margaret had been making a sudden wild attempt to eliminate an unwanted mouth to feed, there seems to have been insufficient evidence for a conviction, but Stace’s biographers, Williams and Meyers, offer the simple conclusion that it was a genuine accident in a chaotic household.

Four years later, in 1880, Margaret’s husband John was imprisoned for assaulting her, and on his release in 1882 immediately sought her out and assaulted her again. Evidence suggests that the whole family lived in fear of this man. Laura escaped to Sydney with Clara but found no real refuge there. She took up with William Stace, an Englishman from a modestly prosperous background, and together they had six children; Arthur was the second youngest, born in 1885.

But William was feckless and, in the deepening depression of the 1890s, could not hold down a job. The family moved frequently among Sydney’s cramped inner-city suburbs, sliding into poverty. By 1892 they were accepting charity, and in November William Stace deserted the family, leaving Laura destitute. Her only option was the Benevolent Society Asylum, a huge institution located near where Central Station is today. After a Christmas spent within those grim walls, Arthur, his older brother William and younger brother Samuel were fostered. Arthur was seven.

Williams and Meyers mention that later in life Arthur would not speak of his time in foster care. The years he blanked out were spent with a family in Goulburn. Later he was placed with families in Wollongong, and as a teenager he found employment in the coalmines there. (With his first pay, he said, he bought a drink: the first step towards decades of alcohol addiction.)

The Stace family was scattered. William and Laura reconciled, but their lives were marred by alcohol and violence, and all their children were fostered or left of their own accord. By the time Arthur returned to Sydney in about 1905, when he was twenty, William had become a chronic and violent alcoholic, and Laura appears to have taken to prostitution. William died in the Parramatta Hospital for the Insane in November 1908, aged about fifty-two. Laura died of cancer in 1912.

Considering all this, the gaps and inconsistencies in Stace’s account of his life are unsurprising. I think he exaggerated his and his family’s criminal associations a little, probably to make his conversion in 1930 seem more powerful. Especially interesting is his claim that as a child he had very little schooling, and that he couldn’t account for his ability to write “Eternity,” and only that word, in perfect copperplate.

Although he implies it was done by some kind of divine guidance, there is ample evidence that he could write quite well and had obviously received some primary education. When Stace said he couldn’t write, the deprivation he was describing was perhaps not education — it was love.

The gap between the shoe and the sock turns out to be vast. It’s not just the gap between Stace the man and what he said about himself, but the gap between the historical sources (newly digitised, many of them) and how we interpret those sources in our own times.

In fact, the gap is so vast I hesitate to approach it because I respect Stace’s telling us only what he wanted us to know. But also, he invited us to wonder, as he wondered, about unfathomable existences beyond our small selves: he walked in the “utmost depths of time and space,” as Douglas Stewart put it.

So let me suggest that what was in that gap was intergenerational poverty, violence, substance abuse and trauma. The twin pillars of Stace’s trauma may have been, first, the poisoning of his half-sister Clara in 1876, and later, his separation from his parents and siblings when he was seven.

What happened on that day in Windsor in 1876? There was baby Clara, “retching and crying.” There was the shock, the panic, the tears and outrage, and the smell of carbolic around Clara’s mouth. All the witnesses would have had their versions of events, but only the baby’s grandmother really knew, and how could Margaret have explained her actions if she herself was a victim of earlier circumstances impossible to describe? How did Laura cope with the memory of that day, and how could she establish a future for herself and her children? Whom could she trust? Not William Stace, as it turned out.

Arthur’s early childhood memories were of sleeping on bags under the house when his parents were “on the drink,” and having to steal milk from verandas and food from bakers’ carts and shops. Fostering might have given him and his brothers proper beds, food and clothing, but at the cost of everything and everyone they had ever known.

Did they know what had happened in Windsor? From under the house they might have picked up bits of it from abusive arguments between their parents, or perhaps it was never mentioned. Either way, spoken of or not, the story was surely always there, impossible to un-remember.

Our increasing knowledge of trauma and its effects on mind and body may offer new insights into Stace’s behaviour as an adult. For years, both before and after his identity as “Mr Eternity” became known, he told his story many times in Protestant services and prayer meetings: how he had been brought up in a “vile” environment, how he had lived a “slothful drunken life,” going from job to job, jail to jail, and how finally, at his lowest point, he had been “plucked from the fires of hell” at St Barnabas’s when “the spirit of the living God” entered his life.

Conversion gave Stace not just a community to belong to — probably for the first time ever — but an audience for his story. It was common in Baptist services for people to give “testimony” by describing their lives before and after conversion, and so here was an accepted language and a template for Stace to craft a narrative of his own. He could stand outside his story and gain comforting distance from it, always with a group of the faithful to take it and hold it for him without judgement.

So then, those half-million eternities could have been another form of repetitious behaviour, born of trauma. His message could have been not only a one-word sermon or a one-word poem, but a one-word trauma narrative. Mightily told, over and over. In those daily pre-dawn excursions around Sydney, the act of kneeling to write “Eternity” every few hundred yards might have put Stace into a meditative state that kept him separated from his past, eternally in the present. Hoping, with his chalk-dry fingers, to convert his suffering into something redemptive for other people. •