Easternisation: War and Peace in the Asian Century

By Gideon Rachman | Vintage | $22.99 | 304 pages

Asia’s Reckoning: The Struggle for Global Dominance

By Richard McGregor | Allen Lane | $49.99 | 416 pages

Without America: Australia in the New Asia

By Hugh White | Quarterly Essay Black Inc. | $22.99 | 128 pages

Asia’s future peace and plenty are a fiendishly complex trillion-dollar conundrum that can be stated very simply: who rules, and who will write the rules?

According to the grand rise-of-Asia narrative, we are seeing the end of the era that began when Vasco da Gama set out from Europe in 1497 in search of new trade routes to Asia, and launched the 500-year epoch in which the West both ruled and created the rules. Against this broad sweep, Donald Trump’s arrival is a mere symptom, not a cause, but he will accelerate the trend in unpredictable ways.

Asia’s rise is the new normal, a defining element of our times, and certainly of the twenty-first century. Australia has been living amid its expansion for so long that the response can be a blasé “ho-hum, what’s new?” Yet almost everything alters when epochs change. New truths emerge and old verities collapse. New rulers strain against old rules.

One of the elemental changes is the erosion of the West’s power to dominate global politics. Gideon Rachman’s statement of this is a conventional rendering of the new normal, but beneath that “normal” the ground shifts and roars. “For more than five hundred years, ever since the dawn of the European colonial age,” he writes, “the fates of countries and peoples in Asia, Africa, and the Americas have been shaped by developments and decisions made in Europe — and, later, the United States.” He goes on:

But the West’s centuries-long domination of world affairs is now coming to a close. The root cause of this change is Asia’s extraordinary economic development over the last fifty years. Western political power was founded on technological, military, and economic dominance, but these advantages are fast eroding. And the consequences are now defining global politics.

Rachman, the chief foreign affairs commentator of London’s Financial Times, is an Atlanticist marvelling at the power shift to the Pacific. His new book (published in the United States with the title Easternization: Asia’s Rise and America’s Decline) is built around the themes of Asia up, America down and Europe out.

Asia’s resurgence, he writes, is “correcting a global political imbalance of political power that has its origins in Western imperialism. In that sense, the rise of Asian powers is an important step towards a more equal world.” But his account of US decline is counterpointed by a “largely positive view of the role of American power in the world.” America’s policing of the rules, he argues, offers the best chance for a just world:

The idea of a multipolar world, without dominant powers and guided solely by the rule of law, is theoretically attractive. In practice, however, I fear that just such a multipolar world is already emerging and proving to be unstable and dangerous: The “rules” are very hard to enforce without a dominant power in the background.

Asia rises, but is divided. Rachman points to two significant obstacles to the Asian century. The first, corruption, eats at the ability of the coming powers, China and India, to create trustworthy institutions for a globalised system: “Popular rage about corruption is a common theme that links democratic India and undemocratic China.” The second, and more serious, is the divisions and rivalries within Asia: “For the foreseeable future, there will be no Eastern alliance to supplant the Western alliance.”

Asia’s rise will be even quicker if it’s accompanied by an American retreat, real or perceived. Image can swiftly shape reality in international affairs, and Rachman worries the notion that America is losing its grip on world affairs is “in danger of becoming conventional wisdom — from Beijing to Berlin to Brasilia.” In power politics, vacuums are always filled, but there’s much jostling, misjudgement and mishap along the way, especially if the occupant of that supposed vacuum vehemently denies that it’s shifting.

Rachman thinks that if the United States has the will then it has the resources to stay near the top of the global rules game. But while America grapples with relative decline, he says, Europe is slipping and slinking out of the contest. Turning his eyes to his own turf, this Atlanticist frets that Europe, which wrote the manual for the world’s system of states, is losing its right to sit at the top table: “The European powers are in precipitous decline as global political players.”

Much changes in the shift from the Enlightenment to Easternisation. Britain has decided to go solo, leaving a smaller Europe led by a Germany that’s determined to stay out of fights. Britain’s “self-isolation,” Rachman writes, is “a potentially shattering blow to European self-confidence.”

The military dimension of Europe’s retreat is what Rachman calls a “breathtaking” reduction in French and British military might over the past forty years. Europe, he says, is gambling with its own security:

The cumulative effect of America’s growing reticence, Germany’s semipacifism, and defence cuts in Britain and France is that the NATO alliance — the bedrock of Western security since the end of the Second World War — is in disrepair. The sense that NATO’s decade-long mission in Afghanistan has effectively failed has further sapped the West’s interest in acting collectively around the globe.

A key feature of our rapidly shifting era is China’s expanding view of its power and prerogatives in relation to the United States. At the end of the twentieth century, China was still following Deng’s admonition to hide and bide — hide its power and bide its time. At the start of this century, it was still easy to sketch the comfortable view that the deep intertwining of the American and Chinese economies and their mutual interest in the global system would define the relationship.

By the time of the global financial crisis in 2008, as America crashed into recession, China had decided it would rise on its terms, not abide by American understandings. The power contest has quickly become intense and sharp, as Rachman illustrates:

Over the course of the Obama administration’s eight years in power, America came increasingly to see China as more a rival than a partner. Quite how far the balance had tipped was brought home to me in the spring of 2014, when a senior White House official told me that he regarded the relationship as now “80 per cent competition and 20 per cent cooperation.” I was so surprised that I got him to repeat the formulation, in case I had misheard — “80 per cent competition,” he said again.

If it took Obama’s team two terms to arrive at that view of China as 80 per cent rival, that perspective is one of the few settled elements of the Trump worldview.

The national security strategy Trump issued in December attacked China as a revisionist power, challenging “American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity,” seeking “to displace the US in the Indo-Pacific region.” The companion national defence strategy issued in January states that “inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in US national security.” America ranks a clash with China ahead of the threat from jihadists. As the Economist headlined, the next war looms as great-power conflict.

Australian official language is more restrained than America’s, but Canberra is just as vexed about what sort of ruler China aims to be. Australia’s 2016 defence white paper fretted constantly about the need for international rules, using the word “rules” sixty-four times, forty-eight of them in the formulation “rules-based global order.”

To see US–China rivalry only in bilateral terms, though, is to miss much that is shaping Asia’s future. Widening the frame beyond the world’s top two economies to include the third-biggest economy, Japan, is what Richard McGregor offers in his new book on Asia’s reckoning and the struggle for global dominance.

McGregor’s focus is on the “cold peace” between Japan and China — the tangled emotions and complex psychology of the Sino-Japanese relationship. “The story of Japan and China,” he writes, “is one of stunning economic success and dangerous political failure.” China harbours “a sense of revenge, of unfinished business” about Japan. The two countries seldom find equilibrium, he says, and rarely manage to treat each other as equals.

Pondering Asia’s future, McGregor is uncertain about what course the US will take: perhaps it will turn its back on the world under an isolationist president, or maybe Pax Americana can survive, with a resilient American economy and refreshed alliances robust enough to hold off an indebted and internally focused China. “The spectre of a renewed Sinocentric order in Asia, though, is upending the regional status quo for good, whatever path the US might take,” McGregor writes:

Geopolitically, the three countries have increasingly become two, with Japan aligning itself more tightly with the US than at any time in the seven decades-plus since the war… As its power has grown, China has begun building a new regional order, with Beijing at the centre in place of Washington. The battle lines are clear.

China’s rise and Japan’s relative decline have fed a poisonous cycle. McGregor quotes a Chinese saying — “two tigers cannot live on one mountain” — to illustrate the view of many Chinese that their competition with Japan to be Asia’s dominant indigenous power is a zero-sum game: “What once seemed impossible and then merely unlikely is no longer unimaginable: that China and Japan could, within coming decades, go to war.”

McGregor is one of the outstanding Asia hands of this generation of Australian journalists. He started as an ABC correspondent in Tokyo, moved to newspapers, and eventually served as chief of the Shanghai, Beijing and Washington bureaus of the Financial Times. His previous book, on the Chinese Communist Party, The Party, was a revelation, built on a framework of fine reporting. Asia’s Reckoning has the same strengths; this is history that draws vivid force from the notebooks of a journalist who did daily duty as the past few decades unfolded.

McGregor describes how, after Japan established diplomatic relations with China, the two enjoyed a high point of “seemingly amicable relations from the late 1970s until the 1980s” as China’s leaders reached out to Japan for investment, technology and aid. Zhou Enlai’s line was that the two countries had enjoyed 2000 years of friendship and fifty years of misfortune. That playing down of history did not become the prevailing view.

Sino-Japanese rapprochement was commercial and diplomatic, but issues of war and history were merely covered over like land mines left just under the surface. As the conflict over history built, McGregor writes, “a corrosive mutual antipathy has gradually become imbedded within their ruling parties and large sections of the public.”

The Chinese government has played the history card — demonisation of Japan — in a desperate effort to maintain its own legitimacy. After the bloody crackdown on the Tiananmen Square demonstrations in 1989, McGregor writes, Japan became “collateral damage” to Beijing’s most pressing priority: to rebuild the party’s standing after having unleashed the military on its own people. Beijing “opened a vast new political front to ensure that such protests never got off the ground again.”

Popular anger must be directed at Japan, not the party. Beijing has stoked rage with “the decades-long party campaign to burnish its patriotic lustre with an unrelenting diet of anti-Japanese history and news.” Beijing’s first use of the now regular criticism of foreigners “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people” was directed at Japan. McGregor quotes the view that the party has raised young Chinese on a diet of “wolf’s milk.”

McGregor offers a masterful account of the complex fifty-year dance between China, Japan and the United States, describing “a profound interdependence alongside strategic rivalries, profound distrust and historical resentment.” His book stays true to one of the central maxims of news journalism: report what you see, don’t be a seer. So McGregor offers little about what might come next: about whether China, Japan and the US are heading to a smash, a muddle through or a major realignment. Granted, publishing at the dawn of Trump throws even more variables into the choices and changes confronting the world’s three biggest economies. Spare a moment’s compassion for the author of a narrative who has to finish his work with the arrival of The Donald. Flux all around and the fog of the future abounds.

The history McGregor offers has plenty of evidence the reader can use to construct two vastly different futures for Japan. I’d call these opposed visions Strong Japan and Comfortable Japan. Marking the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration/Revolution this year is a reminder of how Japan has twice during that period shown the ability to make huge shifts in its governance and society in order to respond to external challenges.

Strong Japan foresees a Tokyo that refuses to bend to Beijing. Japan reclaims its rights as a “normal nation,” building its military strength as America’s key Asian ally and leading Asia in both balancing against and engaging with China. This is prime minister Shinzo Abe’s vision of Japan, reaffirmed by his victory in the October general election. Strong Japan is expressed in the unusual role Abe has taken in leading Asia’s response to Trump: saving the Trans-Pacific Partnership after Trump dumped the trade treaty, reshaping the Japanese constitution, and making a fresh effort to create a “quadrilateral” alliance of democracies linking Japan, the United States, India and Australia.

McGregor’s version of Strong Japan includes his belief that Japan will not be fighting on its own if it does go to war with China in coming decades. He offers a significant judgement about the resilience of the Japanese and Chinese systems in contemplating conflict — and calculating the impact of a defeat: “In Tokyo, a military loss would be disastrous, and the government would certainly fall. But that would be nothing compared to the hammer blow to China’s national psyche should Japan prevail.” He cites the view that such a loss would be terminal for the Chinese Communist Party, marking the moment for regime change.

Comfortable Japan, by contrast, sees Abe as a political outlier who won’t be emulated by future prime ministers. In this version, Japan matches the decline of its population and economy by declining gently to middle-power status. This Japan embraces the peace of its pacifist strain, no longer wanting to serve as America’s unsinkable aircraft carrier. The US–Japan alliance fades away, dismissed as the strange joining of two nations with vastly different histories and values. Putting aside its old nightmares about being betrayed or abandoned by a US turn to China, Japan would drift out of Washington’s orbit. Tokyo could quietly decide that the cost of resisting Beijing is too high.

Comfortable Japan would accommodate China as the new ruler. For the Japanese, this would be portrayed as Japan’s turning back to Asia. In China, the Community Party would proclaim victory in the history war and start to turn down the heat.

If Richard McGregor won’t make any bets on the future in his book, Hugh White puts all his money on red. White thinks China is going to win and America is going to leave. His prediction is that Comfortable Japan will beat Strong Japan because of tensions in the alliance with the United States:

Japan is the key to East Asia’s emerging order as China’s power grows and America’s wanes. Japan’s alliance with America has been the keystone of America’s strategic position in Asia. While the alliance lasts America will remain a major regional power, and when it ends America’s role in Asia will end with it. So we can best understand how America’s position in Asia might collapse by considering the future of the alliance.

The alliance might look robust, but China’s growing wealth and influence has changed the equation:

For America, the costs of the alliance are growing, while the benefits are not. China’s rise makes it both a more valuable economic partner and a more formidable military adversary, and so the costs to America of protecting Japan against China go up both economically and strategically… By the same token, the benefits of the alliance to Japan are falling, as US support in a crisis becomes less certain. This worries Japan more and more as both China and North Korea look more and more threatening. There will come a point when Tokyo reluctantly concludes that America simply cannot be relied upon any longer.

White dismisses the Strong Japan option as too hard. Japan has all it needs to break the nuclear taboo and get nuclear weapons; the difficult part would be explaining the nukes to its own people and getting acceptance from Asia.

A Strong Japan would have to create a coalition of like-minded countries, including Australia, to balance China’s power and prevent Beijing from dominating the region. White judges that the other countries won’t join — all have their own interests with China and all would be reluctant to accept Japan’s direction and serve Japan’s interests — and so middle-power status is more or less inevitable.

In Canberra, Hugh White is always one of the smartest men in the room — and these days one of the most controversial. His customary cheeriness prevails, despite the storms he’s stirred with his writings on Australia’s choice between China and the US. One of the bravura habits of Hugh is his ability to walk into a conference room or lecture hall armed with only a takeaway coffee (muffin optional) and a single sheet of blank paper; the paper is folded down the middle and, before the coffee has cooled, he jots down a series of notes on both sides of the fold. Then he delivers a flawless speech which is both to time and on topic. It’s the performance of a formidable and disciplined intellect, well attuned to the rhythms of Canberra.

After university in Melbourne and Oxford, Hugh White arrived in the national capital in the late 1970s to work as an intelligence analyst in the Office of National Assessments. He jumped to journalism in the parliamentary press gallery (and sharpened his prose style) as defence writer for the Sydney Morning Herald before joining the office of defence minister Kim Beazley and then becoming international adviser to prime minister Bob Hawke. As the defence department’s deputy secretary for strategy and intelligence, he wrote the Howard government’s 2000 defence white paper. He was the inaugural director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and is now professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University.

White’s seer service was displayed in his previous Quarterly Essay, Power Shift: Australia’s Future Between Washington and Beijing, published in 2010. This new Quarterly Essay proclaims that the issue of choice is fading and the result is looming.

The onrush of China has been so central to this decade that it’s difficult to summon up the hysterical response eight years ago to Hugh White’s heresy: the proposition that America should cede some power to negotiate a new regional order, retaining a lesser but still substantial American strategic role in Asia to balance China’s power. As an example of the convulsive response to this proposition, here’s Greg Sheridan in the Australian in September 2010, attacking White’s “astonishing,” “ridiculous” and “weird, weird” essay:

Professor Hugh White of the Australian National University has done something remarkable. He has written the single stupidest strategic document ever prepared in Australian history by someone who once held a position of some responsibility… His central thesis is that the growing strategic competition between the US and China is almost certain to produce deadly and convulsive conflict unless the Americans can be persuaded to give up their primacy in Asia and share power with China as an equal.

Back then, I told White to send Sheridan a big Christmas card of thanks: the gnashing gusher about astonishing weirdness ensured Hugh’s essay had to be read by everyone who mattered in Canberra, and many in Washington. Today we’d be blessed if we’d achieved the comfort of the Washington–Beijing power-sharing agreement that White advocated in 2010. Now he thinks the chance is gone.

White’s new essay judges that the rivalry may proceed peacefully or violently, quickly or slowly, but the most likely outcome is becoming clear:

America will lose, and China will win. America will cease to play a major strategic role in Asia, and China will take its place as the dominant power. War remains possible, especially with someone like Donald Trump in the Oval Office. But the risk of war recedes as it becomes clearer that the odds are against America, and as people in Washington come to understand that their nation cannot defend its leadership in Asia by fighting an unwinnable war with China. The probability therefore grows that America will peacefully, and perhaps even willingly, withdraw.

It’s happening already, says White. And although it is “not what anyone expected,” the process can’t be reversed.

What does Australia face in Rachman’s era of Easternisation and what Hugh White describes as a new regional order delivered by a profound shift in Asia’s distribution of power?

Rachman thinks Australia “faces an acute strategic dilemma,” even as it greets “the rise of Asia with exuberant enthusiasm, treating it as an unparalleled opportunity to secure Australia’s prosperity long into the future.” The dilemma facing Australia and New Zealand deepens if Southeast Asia becomes a Chinese sphere of influence. “Australasia,” says Rachman, “risks becoming an isolated Western outpost, cut off from its political and cultural hinterland. As a result, the vision of China asserting its influence across the South China Sea and in Southeast Asia set off alarm bells in the Australian elite.”

The fear of a coercive China bending Southeast Asia to its will has driven Australia to change its definition of the region from the Asia-Pacific to the Indo-Pacific. “The notion of the Indo-Pacific emphasises India’s importance and challenges the idea of a region that inevitably revolves around China,” says Rachman.

It also stresses the central importance of the Indian Ocean, as well as the South China Sea. And it makes the Australians feel less lonely. Rather than being stuck out on the edges of the Asia-Pacific region, Australia could style itself as at the centre of a vast Indo-Pacific region framed by the two democracies of the United States and India.

Hugh White’s account is of an Australia little prepared for what it faces, especially a US retreat from Asia which, under Trump, “is probably becoming irreversible.” Canberra didn’t see this coming because Washington didn’t expect it, and we have got into the habit of seeing the world through Washington’s eyes. Australia’s misjudgement, White writes, was to depend more and more on America as its position became weaker:

America has no real reason to fight China for primacy in Asia, shows little real interest in doing so and has no chance of succeeding if it tries. Until our leaders realise that, they will not address the reality that we are, most probably, soon going to find ourselves in an Asia dominated by China, where America plays little or no strategic role at all.

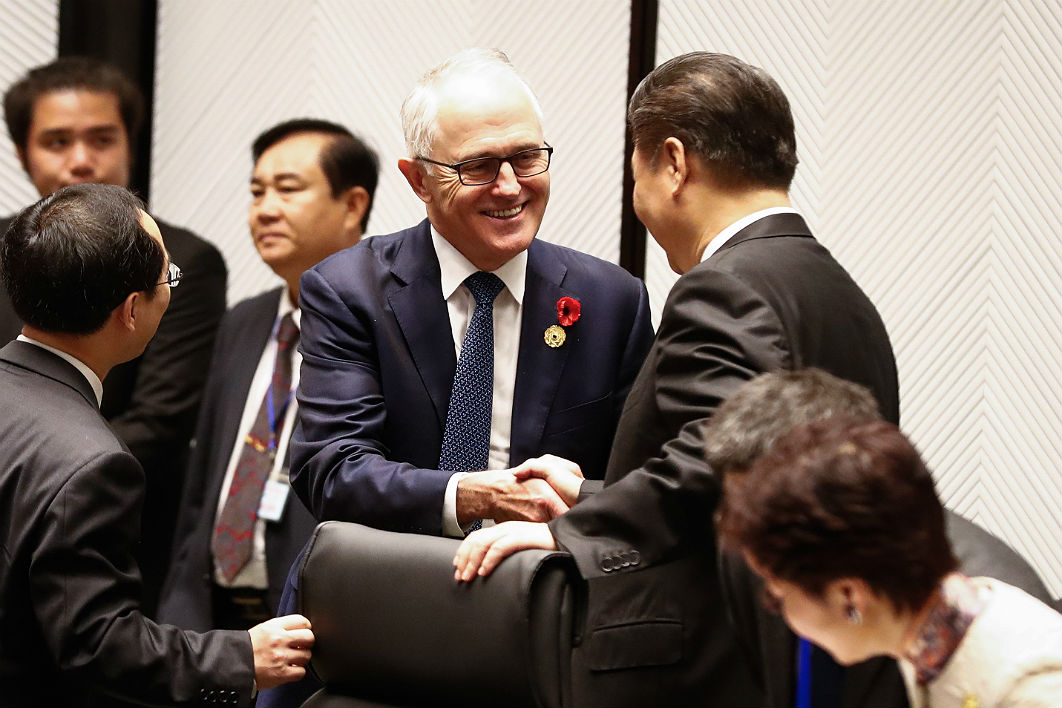

White has cemented his unpopularity in official Canberra because his vision of America vacating the region is completely at odds with the views of the Turnbull government. Its November 2017 foreign policy white paper does describe a new, contested world of great-power rivalry where America’s long dominance of the international order is challenged, but its conclusion is that the US will keep winning:

Even as China’s power grows and it competes more directly with the United States regionally and globally, the United States will, for the foreseeable future, retain its significant global lead in military and soft power. The United States will continue to be the wealthiest country in the world (measured in net asset terms), the world’s leader in technology and innovation, and home to the world’s deepest financial markets. The Australian Government judges that the United States’ long-term interests will anchor its economic and security engagement in the Indo-Pacific. Its major Pacific alliances with Japan, the Republic of Korea and Australia will remain strong.

The structure and conclusion offered by the Australian government can encompass the competition described by Richard McGregor and stretch to take in Gideon Rachman’s Easternisation. But Hugh White describes another world.

We are unlikely to face a single sliding-door moment — a big, one-time choice. We will make constant choices because that is what diplomacy and the world of states is all about. We can no longer chant John Howard’s reassuring mantra that we will not have to choose between our history and our geography.

Our geography presses. China, the United States and Japan — along with India and Southeast Asia — will all be integral to the way we weigh our options and make selections. The constant effort will be to maximise flexibility and minimise zero-sum calls. And Australia isn’t alone in experiencing this angst about our Asian future: it is shared by the other middle powers that will gather at the ASEAN summit in Sydney next month.

China and the United States will push and woo Australia. “We will be able to defy Chinese pressure if we choose,” writes White, “but China will be able to inflict heavy costs on us if we do. It will not be able to dictate to us, but it will be able to shape our choices very powerfully.” A foretaste of how this will go is the Turnbull government’s pushback against China over cyber espionage and perceived interference in our political system, and China’s angry response. This foreign policy quandary has deep domestic roots: in Australia’s census, 1.2 million people declared themselves of Chinese heritage and about 600,000 were born in China.

China’s geopolitical aim is to turn Australia into a neutral, to detach America’s oldest and closest ally in Asia. America fears that Australia will be “Finlandised,” slowly slipping into China’s orbit. White quotes a senior official in the Obama administration venting his frustration about Australia: “We hate it when you guys keep saying, ‘We don’t have to choose between America and China’! Dammit, you do have to choose, and it is time you chose us!”

For his part, Donald Trump threatens to bring a frightening clarity to one of the essentials of the Asian security system: the US military guarantee to Asia, which is of such importance that any future peacetime threat to the formal and informal alliance system will most likely come from the United States itself. Short of war, only major new US demands — or US failures to deliver — could imperil the value of its multi-tiered alliance system in Asia.

A superpower always has the potential to underdeliver or over-demand. Washington will underdeliver if it doesn’t have the means to fulfil its security guarantees to its Asian allies, followers and even free-riders. That underperformance will show first in US political will or regional commitment rather than in the sinews of US military power.

The other end of the same equation is a United States that demands too much from its allies, causing them to baulk. Trump is forcing Asia to ponder both problems, especially the nightmare of an America that could underdeliver by departing.

Even if China were still hiding and biding and America wasn’t being roiled by its president, Australia would confront tougher decisions because of the relative power and wealth we bring to Asia’s table. The key word is “relative”: our long-term relative decline as a power and an economy in Asia continues as it has for decades. That doesn’t signify Australian decline or failure — merely that we are growing at a slower rate than a lot of others in the pack. An ever more prosperous neighbourhood is obviously better for us as well as them, but regional success challenges our power and our choices.

The times will require an independent foreign policy because the times will be tougher. We will fashion our own suit, not ride the coat-tails of others. Australia must be clear about what it sees, and precise in describing it. Our pride in the Australian tradition of straight talking must be matched by even straighter thinking.

An independent foreign policy will demand a capability for independent thinking. For a long time, when Australia talked about China it was actually talking about the United States; that American lens was why we didn’t give diplomatic recognition to China until 1972. Over the past decade, there’s been a flip. Now when we talk about the United States, often we’re really looking at China.

No longer can we afford to allow either Washington or Beijing to frame the other in our thinking. Nor can we see Japan’s strategic options solely through the fifteen-year-old trilateral strategic dialogue of the United States, Japan and Australia — any more than we’re going to deal with India only through the resurrected quadrilateral of the US, Japan, Australia and India.

Australia must see others in the region as their own agents with their own agendas. Lots of independent players will inevitably mean many surprises. Depending on your temperament, it’s an exciting new era or terrifying in its uncertainty. Foundations shift and structures shake.

As a great joiner, Australia wants to be in every conversation and club; but that is just the starting point. Then it’s a matter of how the various clubs and cohorts and Australia itself can contribute to Asia’s future. Independence is more easily declared than displayed; it’s not one of our strongest habits. Just as our geography is going to force us to confront choices, the times will demand independent thought and sometimes independent action. It’s no contradiction to say that an Australia best able to define and declare its independent interests will be better placed to be an ally of the United States, a partner to China, a friend to Japan and a fellow middle power to ASEAN nations.

Australia confronts a rapidly changing Asian system, beset by rivalry and great-power contest. “In this dynamic environment,” says Australia’s foreign policy white paper, “competition is intensifying, over both power and the principles and values on which the regional order should be based.” Power. Principles. Values. We have a core interest in the rules of this game and how the region is ruled, but Australia’s future in Asia doesn’t look much like what we knew during the bipolar stand-off of the cold war or America’s two-decade unipolar moment after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Time to run the ruler over what’s left and start to work for the rules we want. ●