In a little over three years from early 2005 to May 2008, Australia’s working age population, as officially defined, grew by just under a million people. The number of us with jobs grew by a phenomenal 940,000.

Half a decade later, in the three years to December 2014, Australia’s working age population grew by just over a million people. Yet this time the number of jobs grew by only 385,000. For every one hundred extra adults, in other words, we generated just thirty-eight new jobs. Compared to the ninety-four new jobs created for every one hundred extra adults just before the global financial crisis, that’s some shift.

Sure, the labour market did better in 2014, but only slightly. Last year, there were forty-six new jobs for every one hundred new adults – and just twenty-eight of them were full-time.

These figures are another warning that the Australian economy is not doing as well as the cheerleaders claim. If they were right, we would be seeing something like normal growth in jobs. But for six years now, job creation has been nothing like normal; and it still isn’t.

Nor, despite an upturn in job advertising, is it likely to be normal any time soon. The big plunge in mining investment is still ahead of us: it will happen over the next three years, at the same time as the car industry shuts its doors and our main customer, China, struggles with the looming bust of its huge, oversupplied housing market.

We don’t analyse labour market statistics well in this country. Financial commentators focus on the monthly zigs and zags of movements in the seasonally adjusted jobs and jobless numbers, as if they mean something. Usually they don’t. The Bureau of Statistics monthly survey, big as it is, is not big enough to stop the static created by different random samples from drowning out the music of what is really going on.

For twenty years, the Bureau has been telling us to focus on its trend estimates. They iron out the monthly volatility to try to come up with a truer index of what is happening in the labour market. I follow its advice, and those are the figures being quoted here.

Similarly, when you look at the labour market’s performance over longer periods, you get a better understanding of what’s happening than you get by focusing on monthly movements. And when you look at the very long-term data – such as average movements over thirty years – you get a benchmark of what is normal, against which you can judge what is happening now.

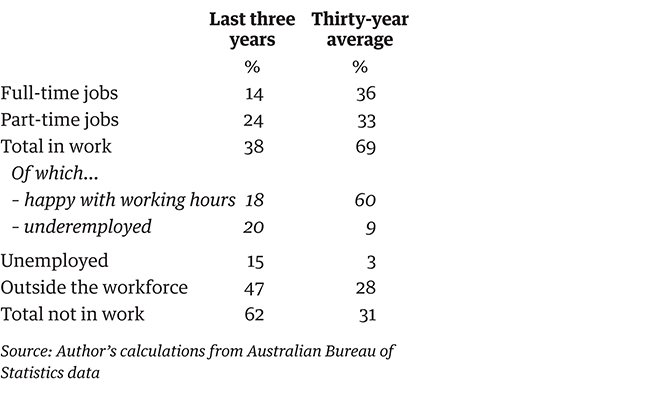

What is “normal” jobs growth, as defined by the past? Well, although the thirty years to mid 2011 saw two recessions and three slowdowns, those years still averaged, in net terms, 690,000 new jobs for every million people added to the working age population – or sixty-nine new jobs for every one hundred new adults.

For every one hundred adults Australia added between 1981 and 2011, in net terms, thirty-six went into full-time jobs, thirty-three got part-time jobs – mostly by choice – three became unemployed, as the Bureau defines it, and twenty-eight either left the workforce or never entered it.

You might think this is a poor outcome. But it wasn’t bad at all, considering that the official definition of “working age” includes everyone aged fifteen and over, including schoolkids, carers and people in their seventies, eighties and nineties who we would not think of as “working age.” And their numbers were growing fast.

Employment climbed from 57.7 per cent of all adults in 1981 to 62.1 per cent in 2011, although almost half that growth was in part-time work. Unemployment fell from 5.7 per cent of the workforce to 5.1 per cent.

Two areas were of concern, though. First, hundreds of thousands of men in their prime years dropped out of the workforce completely. Some were homeless, disabled or suffering from a disabling addiction, or living in areas with no job prospects. In the 1960s, just 2 per cent of men in their prime years (twenty-five to fifty-four) were outside the workforce; now 10 per cent of them are. They are not even looking for work; they have dropped through the cracks.

Second, more than 70 per cent of the unemployed want full-time jobs, but even between 1981 and 2011 almost half of the jobs created were part-time. The Bureau figures imply that 8 per cent of all job growth in that period went to people who took part-time jobs because they couldn’t find full-time work. What it calls underemployment soared from 2.8 per cent of the workforce in 1981 to 7 per cent in 2011.

But what made those thirty years good was that despite an ageing society, workforce participation climbed from 61.2 per cent of the adult population in 1981 to 65.4 per cent in 2011. That was mainly due to the long surge of female employment, which swelled at all ages over twenty-five, with dramatic growth in jobs among older women.

The same has been true for older men, as more and more of us choose to work on into our sixties and beyond: in the year to last June, 26 per cent of Australians in their late sixties – almost 300,000 people – were still in work. Even more surprising, perhaps, 125,000 people in their seventies or eighties were still working. Roughly one in thirty of Australia’s workers are now sixty-five or over.

But far more Australians retire completely in their sixties, and life expectancy among older Australians is rising at startling rates: for men aged sixty, life expectancy is expanding at the rate of nine years in every half-century. That success story is creating headwinds for the economy and the job market, and they are growing stronger each year.

We could be doing a lot better than we are. In the past three years, job growth has been barely half of its long-term average. Let’s look at the numbers to see how the last million Australians to enter adult life (in net terms) have fared, compared to those in the previous generation:

These figures show how much the economy has failed since 2011 to keep up the momentum of the past.

Australia is simply not creating jobs – especially full-time jobs – at anything like the pace needed to regain full employment. Labour-intensive industries such as manufacturing and retailing have struggled or shrunk; and as profits go, jobs go. Manufacturing has lost almost 150,000 jobs since 2008; retailing has added fewer than 20,000 jobs in that time.

Mining construction was the main driver of growth in 2011 and 2012, and it is a capital-intensive activity, creating few jobs. Mining exports have been the main driver of growth in 2013 and 2014, and modern mining requires very few workers, operating very large machinery.

That’s why only 38 per cent of the growth in the adult population has found its way into new jobs. Almost two-thirds of our population growth has ended up swelling the numbers outside the workforce.

The Abbott government has tried to punish the unemployed by making it harder to get the dole – all $36.83 a day of it – and imposing more onerous reporting requirements. But it is clear that they are the victims of the economy’s failure to create enough jobs for those who want to work.

On top of that, most jobs created since 2011 are part-time, yet most unemployed workers want full-time work. The lack of jobs has seen unemployment grow to its highest level since 2002. But because most jobs being created are part-time, the Bureau estimates that the rate of underemployment – mostly, people wanting full-time work, but forced to take part-time jobs – has shot up to a record 8.5 per cent of the workforce.

More than a million Australians are now underemployed, with profound effects on household finances, spending, happiness and general wellbeing. The Bureau estimates that the number of underemployed workers has swollen by 205,000 in the past three years, while the number in full-time jobs grew by 145,000. If someone tries to tell you how well the economy’s doing, just remind them of that.

There’s a third problem. The biggest growth in the adult population is not among those who are employed, or unemployed or underemployed, but among those who are not in the workforce at all.

In the past three years, in net terms, for every one hundred extra people of working age, forty-seven either left the workforce, or never entered it. Some of that loss, maybe half, is unavoidable: it reflects an ageing society, which itself reflects good healthcare. The impact of ageing on jobs is now intensifying as the demographic bulge of the baby boomer generation moves into its sixties; in the weak job market, even employment rates among workers aged fifty-five to sixty-four are now falling.

In four years, the number of adult Australians not in the labour force grew by 650,000. The number in work grew by just 481,000. The number in full-time work grew by just 209,000. That is not a sustainable trend.

These three problems – unemployment, underemployment, and people dropping out of the workforce – essentially reflect a weak economy. But they are intensified by the impact of an immigration policy inappropriate for an economy in low gear.

There are two key differences between Australia now and the Australia of the previous thirty years. The rate of population growth has lifted sharply: in round figures, from 1.25 per cent a year to 1.75 per cent. And that is because the net migration rate has doubled, from 0.5 per cent to a bit over 1 per cent.

Growth of 1.75 per cent means the population is growing by almost 400,000 each year, and by a million every two-and-a-half years or so. It means that when the economy is growing by 2.7 per cent a year, as it is, growth per head (the real bottom line) is less than 1 per cent a year. And it means that an economy our size needs to create more than 200,000 jobs a year – about 150,000 of them full-time – just to stop things getting worse, let alone make up the ground lost since 2011.

A net migration rate of more than 1 per cent means that each year Australia is adding between 200,000 and 250,000 more migrants than it is losing. I have no problem with that, if there is enough work around to employ new and old Australians alike. But the jobs figures make it clear that there isn’t.

The problem is exacerbated because a growing proportion of migrants are being brought here, on section 457 visas and other means, by employers to do specific jobs, rather than employers training Australians to do them. This inevitably means fewer job opportunities for existing workers.

This shortfall could be made up if the temporary workers spent enough money here to employ the existing workers they displace, but that is unlikely. The Bureau does not measure remittance payments – a serious omission in its database – but it is clear that many temporary workers are here precisely because they plan to send much of their earnings home to their families.

In good times, there’s nothing wrong with that either, but these are not good times. Immigration policies need to fit society’s needs; running a high immigration program amid low job demand is bad economic policy. The Menzies government knew better; it controlled the immigration tap to keep the long boom going. We should learn from our past successes.

The result of our employer-driven policy is that people born overseas took almost three-quarters of the net growth in full-time jobs in the two years to April 2013. In net terms, people born overseas gained 97,000 more full-time jobs, while Australian-born people gained just 34,000.

That means the economy created only one new full-time job for every ten Australian-born people aged fifteen and over who joined the notional workforce. That is clear policy failure.

Take all the figures together, and it is clear that the labour market is doing far worse than the trend unemployment rate of 6.2 per cent suggests. The Bureau estimates that its broader measure of labour force underutilisation, which includes the underemployed, has risen to 14.8 per cent. And it does not include the rapidly growing numbers entirely outside the labour force.

Why Australia’s labour market failed so badly after early 2011 is another story, for another day. Poor policy choices must take a lot of the blame. The international environment was unhelpful, but successive governments and the Reserve Bank made bad calls, for which our jobseekers are now paying.

We need to focus more on how we create an environment that will generate the jobs Australians need. •