Since we wrote about the government’s new welfare measures for Inside Story last week, the second coronavirus economic package has added new one-off payments to the mix. The package included some of the most significant (if temporary) changes to social security Australia has ever seen — and legislation passed by parliament on Monday night expanded it even further.

The package effectively doubles the rate of the new JobSeeker payment (formerly Newstart) for most people without children. Until now, a single recipient without dependants received a maximum of $565.70 per fortnight. Lone parents and people over sixty who have been on benefit for at least nine months got more, and each member of a couple got somewhat less. For the six months from 27 April the government will use a time-limited coronavirus supplement to boost the payment by $550 per fortnight.

Importantly, the extra $550 will go to all current recipients, including those who have been getting less than the maximum because they have assets or are in part-time work. It will also go to both existing and new recipients of the youth allowance, JobSeeker payment, the parenting payment, the farm household allowance and the special benefit.

Thanks to Monday night’s amendments, the list of recipients will also include full-time students receiving Abstudy, Austudy and youth allowance for students, bringing to as many as 1.3 million the number of people already on payments who will receive the special supplement.

Added to that — according to the government’s estimate — will be around one million new recipients, who will include permanent employees who are stood down or lose their jobs, sole traders, the self-employed, casual workers and contract workers, all of whom will need to have met the income tests and be jobless because of the coronavirus. Also included will be people who need to care for people who are affected by the coronavirus.

Some conditions will be relaxed. The assets test for three benefits — the JobSeeker payment, the youth allowance for jobseekers and the parenting payment — will be waived for the duration of the coronavirus supplement. The normal one-week waiting period will also be waived, as will the liquid assets test waiting period (which can be up to thirteen weeks). People already in this waiting period will be given immediate access to payments.

Importantly, the coronavirus supplement will be paid automatically. Current recipients will receive the full $550 on top of their regular payment without asking for it.

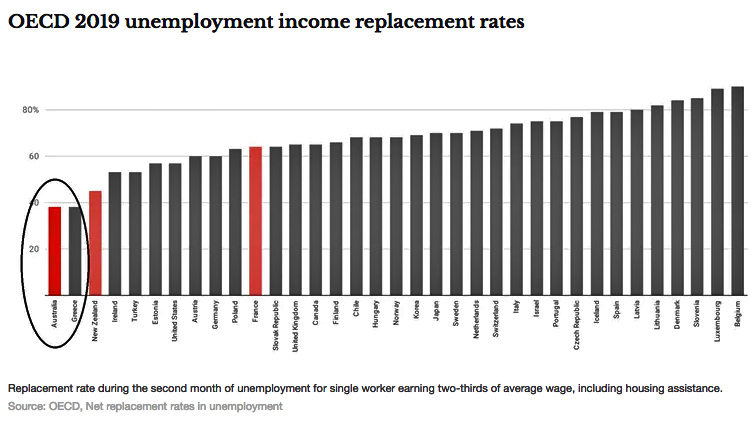

These changes significantly boost Australia’s working-age social security payments, at least temporarily, and push us up the global ranking. As this chart shows, Australia has been at the bottom of the pack compared with the “replacement rate” — the percentage of previous earnings covered by unemployment payments — in other OECD countries.

Courtesy of the Conversation

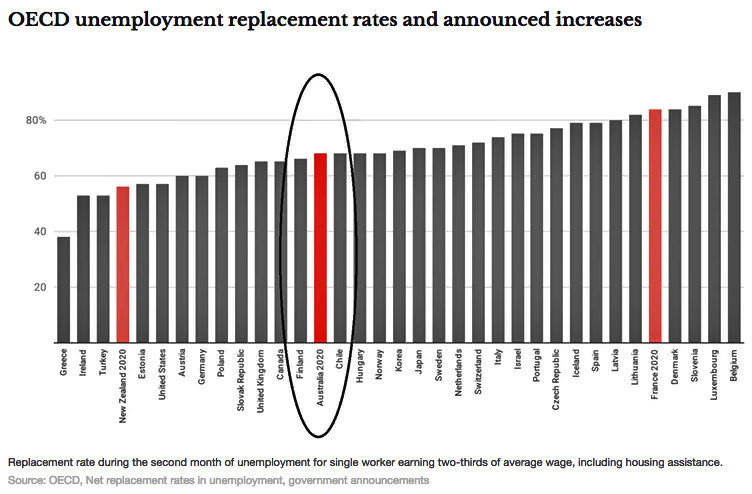

A number of countries have boosted their payments, at least temporarily, in response to the coronavirus. The chart below shows where Australia and New Zealand and France now sit, compared with the 2019 replacement rates of other countries. Australia has risen towards the middle of the pack, with our short-term earnings replacement rate climbing from 38 per cent to 68 per cent as a result of a near doubling of the base rate. (Replacement rates will be lower for higher-income workers who lose their jobs and higher for part-time workers and casuals.)

Courtesy of the Conversation

It is worth noting that other countries are adopting different approaches to target support. Denmark, for example, is providing a direct supplement of 75 per cent of wages to employers, up to a ceiling, on the condition that they don’t lay off workers. That’s less than Denmark’s current replacement rate of 84 per cent, but if it is successful it would effectively mean that Danish workers would continue to receive their normal salary (a 100 per cent replacement rate).

The Australian government has indicated that the stimulus package is “scalable,” meaning that it is possible to increase the dollar amounts even further and extend their duration. It has already fixed some gaps in its initial plan relating to students and newly arrived residents and temporary visa holders. Permanent residents will be eligible for assistance immediately and not subject to current waiting periods, which can be up to four years.

Reports suggest that special payments (and the coronavirus supplement) will be made available to temporary visa holders who lose their jobs or suffer “significant financial hardship” because of the coronavirus. It is unclear, however, whether this will apply to foreign students in Australia and New Zealanders. Another group whose status should be clarified urgently is made up of people who have applied for permanent residence and are still in that application process. A case exists for treating them as if they had already become permanent residents.

A remaining downside with potentially big unintended consequences is the failure, so far, to adjust the spouse income test, which will stop many potential recipients from receiving benefits and create a perverse “benefit cliff.” If a jobless person’s spouse is working and not receiving JobSeeker or equivalent payment, then his or her payment will be reduced by 60 cents for every dollar the partner earns over $994 each fortnight. If the working partner has an income of $1840 per fortnight, the recipient gets the full supplement of $550 per fortnight; if the working partner earns $1850 a fortnight, just $10 more, the recipient gets nothing. Single people face the same abrupt cut-off.

That ceiling on your partner’s earning, $1850 per fortnight ($925 per week), is right in the middle of the Australian income distribution. We calculate that, among two-earner couples aged twenty-five to fifty-four, about half the primary earners who lose their job will get the coronavirus supplement, but only somewhere between a quarter and a third of secondary earners will get it. (These are rough estimates based on Australian Bureau of Statistics income survey estimates of personal income distributions.) Given that in most couples the secondary earner is female, the different treatment has the potential to discriminate against women.

One way to eliminate the cliff would be to better integrate the coronavirus supplement into the income support system, so that people with spouse income above these cut-offs would continue to receive a reduced payment. The government has asked for power to fix this issue via regulation, but has not yet announced how it will tackle it.

An extra million recipients (according to the treasurer) will mean that the share of the working-age population receiving income support climbs from 14.2 per cent to 18.7 per cent. That’s an increase of 4.5 percentage points, bigger than the 3.5 and 3.8 percentage point increases during Australia’s two previous postwar recessions, in the early 1980s and early 1990s.

In both of those recessions, the unemployment rate shot up from under 7 per cent to near 10 per cent or higher within a year. This year’s job losses will occur in half that time, and won’t all be reflected in the unemployment rate. The non-participation rate is likely to rise as people decide to neither work nor look for work. The best measure to watch to track the labour market will be the reduction in hours worked.

International experience suggests that the reduction will be substantial. Service Canada is reported to have received more than 500,000 applications for employment insurance in the past week, twenty times the number recorded in the same week a year ago and equivalent to about 2.5 per cent of the labour force. Similar trends have appeared in the United States. In Australia, we are already seeing the payment system struggling under the load of new applications.

Our economic response to the coronavirus must have a key goal of sharing the economic costs. The government has made an excellent start in the package announced on Sunday and extended on Monday. But we have to be prepared to ramp up and expand support in the interests of fairness. •

This article draws heavily on a piece published yesterday in the Conversation.