The current president of the United States boasts that he doesn’t read books, and for once you believe him. In modern America, it is now surely only a matter of time before people start to brand book reading “elitist.”

This is an opinion already heard about the reading of music. Just last week, at the Canberra International Music Festival, a grandmother was telling me, sadly, that her daughter had announced that her young son would not learn to read music. He was, her daughter had told her, shunning elitism.

People really should look this word up before deploying it. Elitism involves exclusivity. You can only make musical literacy elitist by not passing it on.

Most classical and jazz musicians can and do read music and resent being criticised for it. I think this explains the almost nuclear response to a recent article in the Guardian, in which a journalist, Charlotte C. Gill, argued that the teaching of musical literacy was, in the case of some children, detrimental to musical learning. Gill highlighted the growing discrepancy in Britain between music teaching in private and public schools. This is undeniable (the same discrepancy exists in Australia), and if music education is only available to rich, white kids (Gill’s point), then it might well turn music into an elitist pursuit.

Warming to her subject, however, Gill went on to argue that because some children find it hard to read musical notation, we shouldn’t bother them with it – an elitist attitude if ever there was one! You can imagine the outcry if the same argument were applied to the reading of words.

Still, when the pianist Ian Pace wrote a letter of protest to the Guardian’s editor with more than 600 signatories, including the composers James MacMillan and Michael Nyman, the pianist Imogen Cooper and the conductor Simon Rattle, one felt more was at stake than the views expressed in Gill’s short op-ed piece.

Music notation began in China and in Babylon over 2000 years ago. The systems were both a kind of shorthand, means by which musical ideas might be recorded and so repeated. Notation made possible new sorts of music – literary musical traditions, akin to the literature of poetry, plays and novels allowed by the written word. Different notational systems emphasise different techniques, which tell you a lot about the music they are notating.

For example, the notation for the shakuhachi, the end-blown, bamboo flute of Japan, will often give more information about the gestural quality of the note than its actual pitch. Because Western music is mostly harmonic in nature (unlike the majority of Eastern music), its notation stresses pitch and duration but tells you next to nothing about tone quality. But Western notation also allows the composition of elaborate musical structures.

When Frederick the Great of Prussia was showing off his new fortepiano to Johann Sebastian Bach at the Potsdam Palace in 1747, he presented the composer with a long and rather convoluted theme, possibly of his own devising, challenging Bach to improvise a three-part fugue on it – that’s to say a rigorous, developing structure in three simultaneous “voices.”

There can’t have been many musicians capable of making up a three-part fugue on the spot, but Bach was not only one of history’s great contrapuntalists, he was also one of its best improvisers, and he duly obliged.

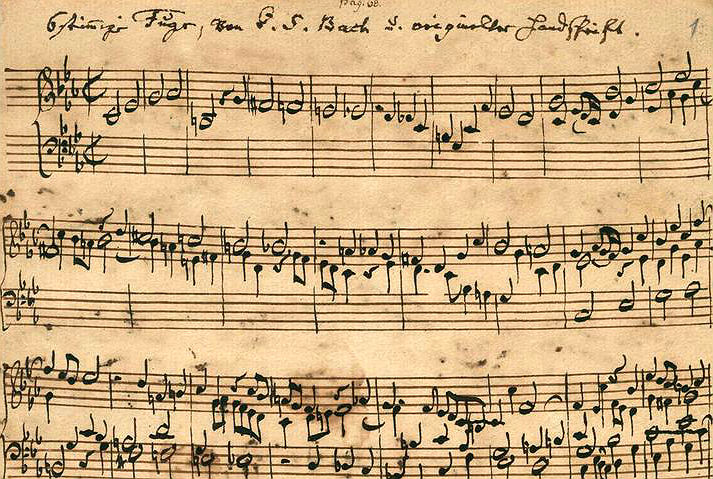

Frederick must have been a little disappointed, because he immediately upped the ante, proposing a six-part fugue. At this point Bach demurred, explaining that he would have to take it away and work it out on paper. A couple of months later, he delivered The Musical Offering, an entire collection of pieces based on the king’s theme, comprising some of the most complex contrapuntal music ever created – including that six-part fugue, or Ricercar.

Of course, it’s unlikely that the three-part fugue in the final version of The Musical Offering exactly matched the fugue Bach improvised for the king, because it would have been virtually impossible to remember all the details. It would be equally hard to recall the details of a solo by John Coltrane or Frank Zappa if we didn’t have sound recordings. But in addition to listening to A Love Supreme or Hot Rats, there have always been those fans of jazz and rock who wanted to see the music written down, presumably to see how Coltrane and Zappa did it.

In fact, these transcriptions revealed nothing of the sort. For Coltrane and Zappa, though highly musically educated, did not represent literary traditions. Their art, for the most part, was improvisatory, their ecstatic lines spontaneous and never the same twice: to see them transcribed, the intricacies rendered in hundreds of dots and complex rhythms, is to learn very little. This is not how these musicians thought, and one doubts either could have played his own music from this notation.

Bach’s music – and this goes for most of what we loosely call “classical” music – is avowedly part of a literary tradition: approximately 800 years of Western art music that in most cases could only have been worked out on paper. You can’t improvise something as complex as The Musical Offering or Beethoven’s Missa solemnis or Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung. There’s plenty of ecstasy here, too, but it was devised on the page, the score a blueprint for a grand musical design that will be built and rebuilt with each successive performance. When Frank Zappa wanted to compose for the orchestra, which he did more and more towards the end of his life, he, too, had to produce these blueprints.

Academics have tended to hold the written word in higher esteem than the spoken, presumably because they hang out in libraries. Perhaps it is for this reason that some people believe written-down music to be superior to other music. It isn’t; it is simply different, and its structure is often more complex.

It is not hard to learn musical notation – though, as with anything in education, there will be those who find it harder than others – and people who can read music aren’t especially clever: learning a foreign language is far more difficult. Nor do you have to be able to read music in order to appreciate Bach or Beethoven or Wagner – or the orchestral works of Frank Zappa.

But the ability to read music opens up a new dimension and a deeper understanding of the work of those great minds. The more we encourage it and provide access to it, the less anyone can accuse classical musicians of being elitist. •