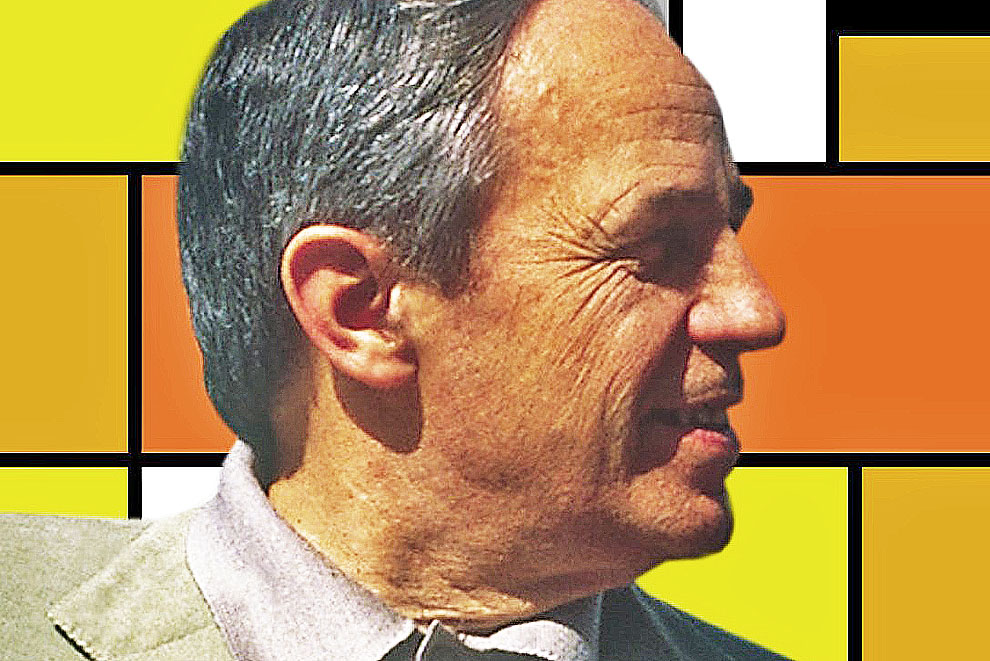

As a conductor, the composer Pierre Boulez has one of the most significant recorded legacies of the past half-century, which includes a number of works no one else has ever recorded. He set new standards for accuracy and clarity in orchestral playing, particularly in his recordings of Debussy, Stravinsky and the composers of the second Viennese school, Schoenberg, Webern and Berg.

Boulez turned ninety in late March, though the man himself was too frail to play any part in the public celebrations. It is now two years since he conducted a concert, his eyes having let him down, so that was never an option, but neither were there any interviews or even so much as a public statement.

And yet, represented by his music, Boulez was everywhere, in Europe especially. He was also everywhere in the press in tributes that had the ring of early obituaries, and in reviews of his recordings, nearly all of which had been imaginatively repackaged to mark this anniversary: Sony, Erato and Deutsche Grammophon released, between them, four boxes of recordings containing 135 CDs. What was disappointing was the extent to which the mainstream press relied on the lazy regurgitation of clichés in its consideration of the conductor’s work. Yet again we read that the performances were analytical, intellectual and arid; that Boulez x-rays the music but fails to display its flesh, his interpretations lacking warmth and affection. But then you start listening, and realise that’s mostly tosh.

Because he is a composer himself, Boulez the conductor has always set out to reveal the contents of a score. It wasn’t that he resisted interpretation – decisions have to be made about tempo, dynamics, phrasing and so on, and that is interpretation – but he never brought affectation to his music making. When critics wrote that Boulez’s Bartók wasn’t Hungarian enough, that his Mahler lacked the authentic Viennese schwung, what they meant was that he didn’t exaggerate the music; they were regretting his refusal to put on a Hungarian or Austrian accent. This is one of the reasons I like his Bartók and Mahler.

The x-raying charge stemmed from Boulez’s fastidious approach to tuning and orchestral balance. In a Boulez performance, you heard a lot of information. The different strands were unpicked, the inner parts revealed; in broad terms it was the opposite of Herbert von Karajan’s approach to the orchestra, which involved moulding the contributions of a hundred musicians into a burnished, monolithic whole. When Boulez’s first recordings of Debussy’s orchestral music appeared in the 1960s, they were revelatory. Hitherto, a piece such as Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune had seemed vague and languorous, but now all was clarity, and the performance itself quite swift. Boulez believed Debussy’s little tone poem, composed in 1894, was the beginning of modern music, and listening to his recording you could hear why.

Boulez made the bulk of his records for Columbia (now Sony) between 1966 and the mid 1980s and for Deutsche Grammophon from 1992 to 2012. Over this time he worked with most of the world’s best orchestras and the cumulative experience made him, in his own estimation, a better technician at the end of his career than at the start, allowing him greater “flexibility” (a favourite Boulezian term). There is considerable overlap in his repertoire for Columbia and DG – the orchestral works of Berlioz, Debussy, Bartók, Stravinsky, Ravel, Webern and Varèse were all recorded, more or less complete, for both labels – and it’s interesting to compare them. Naturally the sound quality is better on the later DG discs and often the playing is too, but they also seem more mainstream. In terms of its running time, Boulez’s second recording of L’après-midi d’un faune is slightly faster than his first, but it doesn’t seem it. Perhaps that extra flexibility resulted in more natural phrasing, banishing the slight air of breathlessness on the earlier recording, but the sense of revelation had gone.

I find myself continually drawn back to the conductor’s first thoughts about his core repertory, courtesy of a beautifully presented box of the Columbia recordings decked out in miniature facsimiles of their original LP jackets. Apart from the composers mentioned above – together with Berg and Schoenberg (composers to whom Boulez has not returned so much in the studio) and Boulez himself – the box includes some fascinating oddities, not the least of which is a very slow account of Beethoven’s fifth from 1968. It was recorded with Otto Klemperer’s New Philharmonia Orchestra and one is tempted to conclude that slow Beethoven must have been in the orchestra’s blood, except that even Klemperer wasn’t this slow. The odd thing is that I keep returning to it. The tempo is wrong (for once, Boulez has overridden the composer’s marking) but the performance is very powerful indeed, rhythmically driven and ultimately overwhelming.

In the 1980s, in between his work for the two big companies, Boulez made some important recordings for the French label, Erato, mostly with the Ensemble Intercontemporain. These included a lot of small-scale Stravinsky, and music by Boulez’s contemporaries, such as Carter, Kurtág, Donatoni, Birtwistle, Grisey, Ferneyhough and Xenakis. Many of the recordings are of works you won’t find anywhere else and they are collected together in an indispensable new Erato box set, along with larger-scale works by Schoenberg, Stravinsky’s opera, The Nightingale, and a number of Boulez’s own pieces.

DG has just re-released a box of recordings that predate everything discussed above. In the 1950s, Boulez formed the “Domaine musical” at the Marigny Theatre in Paris under the patronage of the actors Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud (the young Boulez had been music director of their theatre company). Here he explored the music of the second Viennese school for the first time – not only Boulez’s first time, but also France’s. As with some of those early Columbia recordings, there’s a pioneering spirit evident in the performances, and the discs have considerable historical significance, including the first recordings of Stockhausen’s Kontra-Punkte, Messiaen’s Sept Haïkaï and Boulez’s Le marteau sans maître. And there’s Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony Op. 9 in a performance from 1964 that tears along, taking seriously the composer’s metronome markings. The sound quality is boxy, but the performance is incredibly exciting.

DG’s main contribution to the Boulez birthday is a box of his recordings of twentieth-century music from his later period, including his second thoughts on Debussy, but strangely not his Mahler. Boulez’s discs of Mahler symphonies and songs are, for me, his most important achievement with DG. He had wanted to record Mahler at Columbia, but was sharing a label with Leonard Bernstein and Columbia didn’t need another Mahler cycle.

Nevertheless, Mahler’s symphonies have been a mainstay of Boulez’s concert repertoire since the 1960s, and the recently completed DG cycle – the final instalment was Boulez’s last release in 2013 – contains as much clarity and revelation (and therefore provocation) as his Debussy had in the 1960s. For Boulez, Mahler was not just the end of Romanticism, he was a Janus-like figure, simultaneously looking forward to the second Viennese school. These are the symphonies of a proto-modernist. There’s no sentimentality here and barely a whiff of old Vienna, unless Mahler has written it into his score. The Mahler symphonies are available in their own box, and they represent hours of fascination and, even if you know them, the thrill of discovery. •