Strong exports have been one of the key pillars of Australia’s economic growth in the past decade. In sheer volume, the amount of stuff we sell the world has grown in that time by close to 60 per cent, and average export prices are now at an all-time high.

But that pillar of our growth stands on one country, and virtually one country alone.

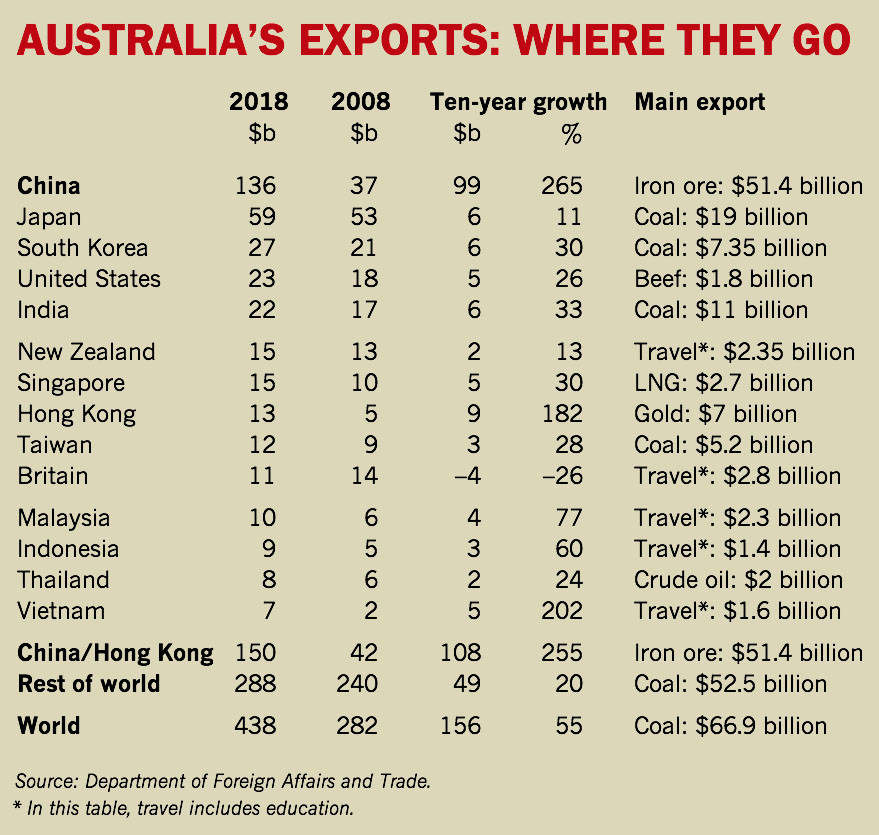

Between 2008 and 2018, Australia’s annual export revenue grew by $156 billion. But $99 billion of that came from a boom in exports to that country, and a further $9 billion from exports to its gateway.

The country was China, its gateway Hong Kong. Together they have generated an incredible 70 per cent of all Australia’s export growth in the past decade — more than twice as much as the rest of the world put together.

Never in the postwar era has any country been so important to our economy. In the past decade, exports to China and Hong Kong shot up by $108 billion. Exports to the United States grew by just $5 billion (what a fizzer that free-trade agreement was!). We’re often told that India could be our alternative to China, yet exports to India in the same decade grew by just $6 billion.

China’s demand and our massive immigration program are what has kept the Australian economy growing. The reason the conventional wisdom can claim Australia escaped a recession in 2008–09 is that China responded to the global financial crisis with a massive construction program, using Australian iron ore and coal. In the two years to 2009–10, our exports of goods to China shot up by $19.5 billion, or 72 per cent. Our exports to the rest of the world rose by $0.4 billion, or 0.2 per cent.

There are echoes of that in 2019. To prevent the Trump tariffs dragging China’s economy down, president Xi Jinping has revved up China’s construction activity even higher, and once again it’s Australian iron ore and metallurgical coal that have been the big winners. Their prices have soared and our terms of trade have jumped to a six-year high, and these results have helped keep the economy growing and put the budget almost back in the black.

Yesterday treasurer Josh Frydenberg declared, “As a result of the Morrison government’s economic plan and responsible budget management the budget has returned to balance for the first time in eleven years.”

Well, no, treasurer. In fact, the budget is still in deficit by $690 million. And while that is nearly in balance, it’s due to a massive $6.1 billion underspend in 2018–19 on the National Disability Insurance Scheme, higher than expected income tax receipts — and a $4.6 billion windfall in company tax revenue, thanks to China.

Australia has experienced export dependency before, but it’s a long time since Britain ruled the waves and bought half our exports. Even our dependence on exports to Japan in the seventies and eighties was nothing like this. When two-thirds of our export growth relies on one country, we are seriously dependent on it to provide for our future. And that matters for three reasons.

• First, it makes us highly vulnerable to the Chinese applying economic pressure to secure political/diplomatic goals. An example we rarely discuss: we support the US freedom of navigation patrols in the South China Sea, and no doubt the PM will repeat this at the weekend in Washington, but we refuse to join them, for fear of Chinese retaliation. And when even Australia won’t join the United States in these patrols, no Asian country dares do so.

• Second, when China’s economy falters — as one day it will, and possibly quite soon — it will take Australia down with it. China has chosen to keep pursuing a pattern of growth that is very favourable to Australia’s export mix. But it is unsustainable, and when it collapses, it is likely to be succeeded by a long drought in those same exports.

• Third, when the United States and China eventually end their trade war — as one day they will — part of the settlement will almost certainly see China ordering its importers to buy American goods, in areas now dominated by Australian exports.

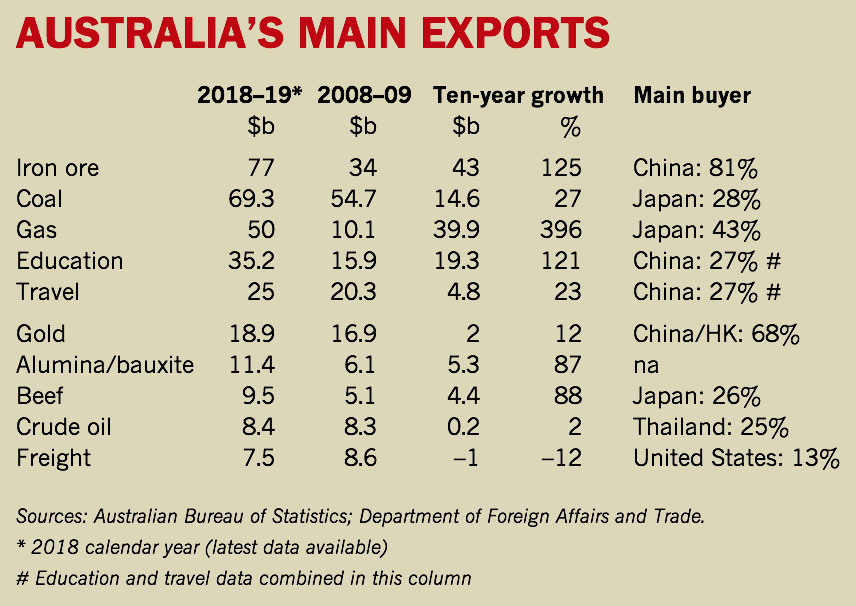

Some of our key exports have a frightening dependence on China.

Last year China provided 81 per cent of export revenues for iron ore — now our biggest export earner. Together with Hong Kong, it bought 68 per cent of our gold, and by itself it provided 59 per cent of export revenues from confidential trade (usually alumina) and 79 per cent from miscellaneous minerals.

Okay, if demand drops, minerals can be stockpiled indefinitely: but their prices will fall, and if demand drops steeply, Australian miners could suffer big falls in export volumes and prices alike. The very forces that have inflated our growth will work to deflate it, and that will hurt.

China has not only been buying minerals. It’s also become the biggest buyer of our farm produce. China comprises the vast bulk of Australia’s export market for wool, barley, prawns and other crustaceans, woodchips, cotton, and miscellaneous foods (mostly fast-growing new exports). Of Australia’s key exports that have seen rapid growth in the past decade, all but one owe that growth to China. (The exception is beef, where Japan remains the biggest market, but China is making up ground fast.)

Until recently, on its own figures at least, China was the world’s fastest-growing economy. Australia has been fortunate to be able to swim alongside it, in a relationship that has worked for both countries.

Indeed, it has created dependence at both ends. As Angus Grigg and Angela Macdonald-Smith documented recently in the Financial Review, China now relies on Australia to supply three-quarters of its iron ore imports and almost half of its LNG. Security analyst Ross Babbage told the Fin: “China is in some respects more dependent on us than we are on them. This is one of the reasons why the leadership in Beijing is cautious about pushing Australia too hard.”

To date, Australia has been perhaps the biggest beneficiary of the China–US trade war. Other Asian countries normally export lots of components to China to be assembled there for export to the United States and elsewhere. That trade has been severely hit, whereas Australia’s China-bound exports over the year to June soared by $28 billion, or 27 per cent. That rise is likely to be undone, one way or another, as the trade war comes to a crisis.

It certainly hasn’t happened yet. The stimulus measures the Chinese government has taken — such as ordering developers to build more new apartments on top of the fifty million empty ones already in China’s cities — require plenty of steel, which in turn requires even higher imports of Australian iron ore and metallurgical coal. And its diversion of import demand from the United States — which had been its main source of LNG — has only made Australia more important.

But it won’t last. Our gains will unwind when the trade war ends and Chinese demand is diverted from Australia to the United States. Demand for our iron ore and metallurgical coal will shrivel when China decides there’s a limit to how many empty apartments it can build. And there are good reasons why China itself might want to stop producing more than half the world’s steel and aluminium.

There are also good reasons why Australia should want to reduce its economic dependency on a superpower that in other ways has shown itself far from friendly to us.

The economic pain we are feeling is coming from the domestic economy. On the global front, our trade surpluses have grown very large — partly because China is buying up big, and partly because we are not. The June quarter saw Australia record its first quarterly current account surplus since 1973.

But another view is that, in net terms, it means we’re investing more in the rest of the world than it is investing in us. About time, you might say, but it’s happened partly because business investment is now exploring its lowest levels in decades as a share of GDP.

The domestic economy is on the ropes. The Bureau of Statistics estimates that unemployment this year has grown by 45,000 — only from 5 per cent to 5.25 per cent, but the National Australia Bank’s monthly business survey confirms that business confidence is low and heading lower. Almost half the jobs created this year have been part-time, and half of them have gone to people who want more work — usually full-time.

The youngest generation of workers — those aged fifteen to twenty-four — are getting it in the neck. On the Bureau’s preferred trend measure, there are 2.225 million of them in the workforce, up 30,000 this year, but the number in full-time work has grown by just one hundred. The number unemployed has grown by 13,000, while the number underemployed — mostly people who want full-time work but can only find part-time jobs — has swollen by 28,000.

The Bureau estimates that 30 per cent of all workers in this age group are now “underutilised.” What will happen to the rest of them if the pillar of China’s support to our economy crumbles, and falls? •