Strange as it may sound, advocates of greater government transparency could have a Chinese infrastructure company to thank for Australia’s recent step towards exposing the secret work of lobbyists. The new rules might be tentative and partial, but they could form the basis of a fully-fledged disclosure system.

The story begins with the Rizhao-based Landbridge Group’s successful bid for a ninety-nine-year lease of the Port of Darwin in 2015, which prompted soul-searching in Canberra about how best to protect strategic assets from the large sums of Chinese cash sloshing around international markets. The result was a set of new laws and procedures to regulate investments by companies owned or controlled by foreign governments (China is never mentioned by name). And those laws came with what seemed like a minor footnote — an enforceable public register for lobbyists — that began throwing fresh light on Australia’s underregulated lobbying industry.

Since 10 December 2018, anyone lobbying Australian officials on behalf of a foreign government or a company controlled by a foreign government — and almost all Chinese companies are likely to fall into that second category — must sign up to the Transparency Register. Failure to fill out the form comes at a significant price: violations of the 2018 Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act can lead to prison terms of up to five years, depending on the seriousness of the omission. Landbridge’s high-profile Australian consultant, former trade minister Andrew Robb, reportedly ended his association with the Chinese company during the new legislation’s grace period.

Because the legislation applies only to what it calls “foreign principals,” the Transparency Register illuminates a very narrow subsection of the lobbying industry. Lobbyists representing Australian businesses or foreign companies that aren’t government owned or controlled are still free to ply their trade without having to worry too much about the separate but much weaker Australian Government Lobbyist Register, which was established under the 2008 Lobbying Code of Conduct.

Even so, the Transparency Register represents progress for a country that has a comparatively weak record of transparency — a record compounded by the inadequacies of Australia’s freedom of information laws and the absence of rules to prevent officials from moving freely between government and private enterprise. By contrast, the US Lobbying Disclosure Act forces all lobbyists to sign up to a public register or face a fine or a jail sentence of up to five years.

But for those with the time and inclination, a delve into the Transparency Register does offer real insights into how “foreign principals” target government ministers and MPs. It tells us, for example, that former foreign minister Alexander Downer is registered as a lobbyist on behalf of the British overseas territory of Gibraltar now that Britain has taken back control of trade negotiations from Brussels. It also tells us that Sanlaan, the firm of Howard government minister Santo Santoro, has engaged in “general political lobbying” and “parliamentary lobbying” for the Port of Brisbane, partly owned by a Canadian superannuation fund backed by the provincial government of Québec, and has also worked for Beijing Jingneng Clean Energy (Australia) and other Chinese renewable energy companies.

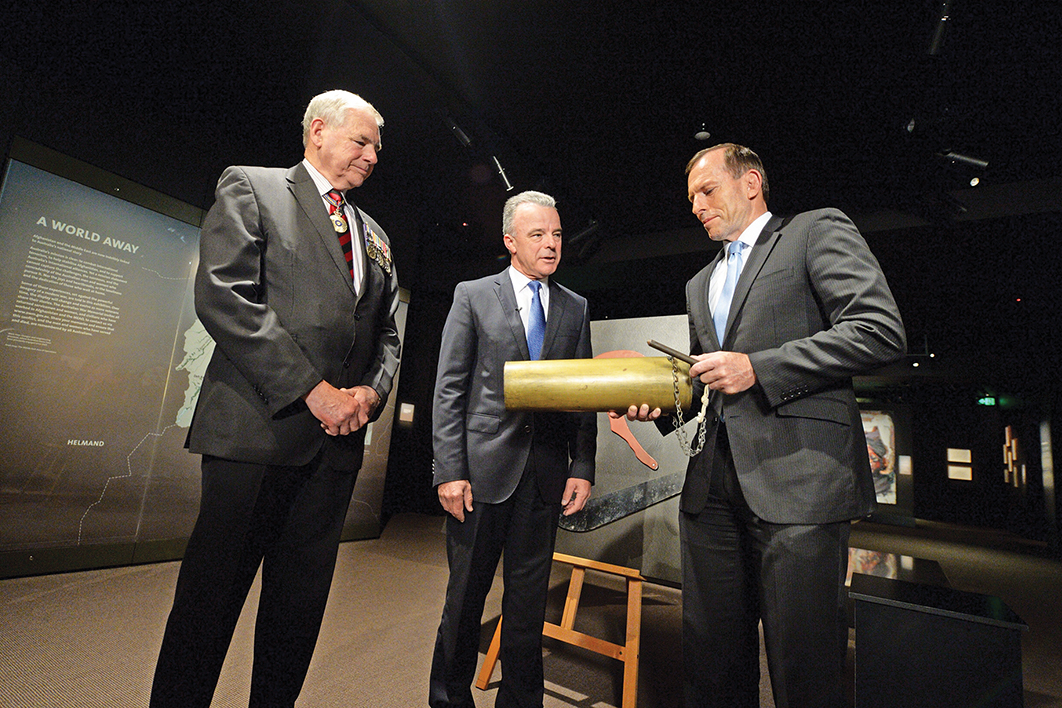

Other celebrity lobbying figures on the Transparency Register include one Anthony John Abbott, who declares that he is an “unpaid adviser to the UK Board of Trade” with the role of “advocat[ing] for free and fair trade, especially trade with the UK and its allies.” In other words, the former PM will be lobbying his former colleagues in Australia to help bring about a trade deal that British prime minister Boris Johnson desperately needs as part of his post-Brexit narrative.

Abbott’s decision to register is controversial because he once described calls for him to sign up as a result of a gig speaking to foreign conservative leaders as “absurd.” He also warned journalists “to rethink the making of such misplaced and impertinent requests in the future.”

Kevin Rudd, another former prime minister, has made his dissatisfaction with the law’s lack of clarity publicly known via an essay in his Transparency Register entry describing the uncertainty about whether he needed to register. Rudd lists all the government-owned foreign media outlets he has appeared on — from the BBC to the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation and Radio New Zealand — because they are state-owned and, he argues mischievously, may fall within the law’s current wording. He says that requiring a former prime minister to list his media appearances, as well as unpaid speeches to the European Parliament and the National University of Singapore, amounts to an absurd interpretation of the law, albeit one that he has been forced to accept.

More importantly, though, while the Transparency Register may reveal that Kevin Rudd isn’t above appearing on Canada’s TVOntario, the information he provided is still insufficient to allow the public to join the dots. We may know that Alexander Downer is lobbying for the Gibraltarians, but we don’t know whom he has spoken to and the matters being discussed. That information is key for anyone trying to establish a connection between lobbying efforts and government decisions. What’s more, the Transparency Register offers no insight into the activities of companies that aren’t owned or controlled by foreign states.

What these cases highlight is that Australia’s transparency system doesn’t stand up well internationally. If you type the name of Chinese technology giant Huawei into the search engine of Ireland’s lobbying register, for example, you will find a list of meetings held by the company and an explanation of the matters discussed. On 17 January, Huawei disclosed that it had met Heather Humphreys, an Irish minister, to discuss “the investment of €70 million in Irish R&D and the creation of 100 new jobs.” That’s marketing spin, to be sure, but when added to previous entries it’s clear Huawei was lobbying to play a part in the country’s rollout of new 5G technology. We also know that the company was in touch with the government via PR and lobbying firms, whose telephone numbers and email addresses the Irish register helpfully includes.

That’s not to say that Ireland’s transparency regime has all been smooth sailing. I was working in Europe when the register took effect, and an Irish lobbyist told me that when he saw a local politician at the supermarket at the weekend he would turn the other way to avoid having to spend his Monday morning filling out disclosure forms. What’s more, the administrative burden of such transparency requirements tends to fall more heavily on small community groups. Extensive and probably time-consuming entries in the register tell us, for instance, that the charitable Irish Guard Dogs for the Blind organisation has been in regular contact with the Irish government.

Australia’s Transparency Register tells us, for example, that between March and December 2019 former defence minister Brendan Nelson took on a role with the Thales Group, the publicly listed, Paris-based company that provides technology for military, aerospace and transport projects. But whom did Nelson speak to on behalf of Thales? And what did they discuss? The register doesn’t offer any answers and the arrangement was only picked up because of the French state’s 25 per cent ownership of Thales.

The parallel Lobbyist Register, which lists third parties but not direct contact from company managers, doesn’t mention either Thales or Brendan Nelson. As for the network of state-based transparency registers, Thales only appears in New South Wales, where it’s represented by a firm listed as Lyndon George, co-owned by a former senior adviser to John Howard, Hellen Georgopoulos. None of this information sheds light on what Thales got out of its relationship with Nelson and how his work may have affected government.

This leaves freedom of information requests as the only fallback, and here the frustrations multiply. Several years ago, I heard that US software company Oracle had met with officials at the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner to brief them on privacy concerns surrounding Google. We know that Oracle had been fighting the search giant in a US court for over a decade, but what was said in those meetings? Neither the ACCC nor the OAIC revealed whom they spoke to as part of their investigations, and Oracle wasn’t talking either.

Even if the foreign-lobbying laws had applied back in 2017, they wouldn’t have picked up these meetings because Oracle isn’t owned or controlled by a foreign government. The more general Lobbying Register would not have been much use either, because it only includes “third party” lobbying firms rather than direct contact between the company and state officials. And unlike, say, the European Union’s competition commissioner, the ACCC doesn’t publish daily lists of meetings attended by its top officials, making cross-referencing impossible.

I made a freedom of information request to both the ACCC and the OAIC that yielded correspondence confirming the meetings had taken place but little about what had been discussed. The central slideshow presentation made by the visiting Americans couldn’t be released, I was told, because the company had objected. Almost two years after I had filed my FOI request, an Administrative Appeals decision produced the full slide show, which laid out what became the ACCC’s consumer-law court action against Google over the data collected by its Android devices.

That’s not to say there was a causal link between the two — the ACCC may well have been planning the enforcement action anyway. Transparency is simply designed to let the public know who is being lobbied by whom, and about what. A two-year wait for documents frustrates and ultimately derails any attempt to understand how lobbying unfolds.

The Transparency Register came into being as part of Australia’s revamp of foreign investment and security policies after the Port of Darwin controversy. The sweeping changes included tougher rules for foreign investment, a new agricultural land register, and the creation of the Critical Infrastructure Centre, which would draw a line in the sand for foreign government–backed companies looking to invest in Australia. New laws also awarded the government the power to veto significant investment plans signed by Australian states and territories involving foreign companies owned or controlled by foreign governments — the same laws that last week dismantled Victoria’s Belt and Road deal with China and may now be used to unwind Landbridge’s control of Darwin’s port.

These rule changes also revealed fissures between Treasury, traditionally supportive of foreign investment, and a home affairs department preoccupied with espionage and the security implications of Chinese control of key infrastructure. Until now, the Foreign Investment Review Board has assessed foreign takeover bids and the treasurer has had the final say. But the new Critical Infrastructure Centre is part of home affairs and its focus is rooted in security concerns rather than economic considerations.

Chinese control of Darwin’s port may indeed raise espionage concerns — this is the criticism that was levelled in 2015 by former US secretary of state Richard Armitage, who was concerned about the movements of US navy ships being monitored by the Chinese-run operation. And Canberra’s August 2018 decision to exclude Huawei and fellow Chinese telecommunications company ZTE from the 5G rollout could also be justified on those grounds.

But stopping Chinese companies from owning gas pipelines or agricultural land remains highly controversial. Some observers question the fear that China could turn the tap on a domestic Australian pipeline during a conflict or export food from Australian farms without Canberra’s consent. Yet the Critical Infrastructure Centre’s job description is indeed to list “those physical facilities, supply chains, information technologies and communication networks which, if destroyed, degraded or rendered unavailable for an extended period, would significantly impact the social or economic wellbeing of the nation” — a definition that shoehorns the home affairs minister into a Treasury-based decision-making process.

But perhaps the Treasury and home affairs perspectives were already converging. In November 2018 treasurer Josh Frydenberg announced he would block the $13 billion acquisition of APA Group, Australia’s largest natural-gas infrastructure business, by a consortium led by Hong Kong’s CK Infrastructure. Treasury already appeared to be falling into line with home affairs — a shift that had arguably been on the cards since former ASIO head David Irvine was appointed to run the Foreign Investment Review Board.

Of course, the push for greater transparency in foreign lobbying doesn’t appear to have been motivated by a broader interest in aligning Australia’s lobbying rules with the United States or some European countries. In fact, you could argue that the erosion of funding for the OAIC, which attempts to oversee freedom of information, and the government’s unwillingness to release unredacted documents continue to tarnish Australia’s international reputation.

Nonetheless, as a map of foreign political lobbying in Australia by foreign companies, the Transparency Register is an important tool. It also provides a blueprint for an expanded and legally enforceable lobbying register that could shed important light on what takes place behind Australia’s closed doors. •

The publication of this article was supported by a grant from the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.