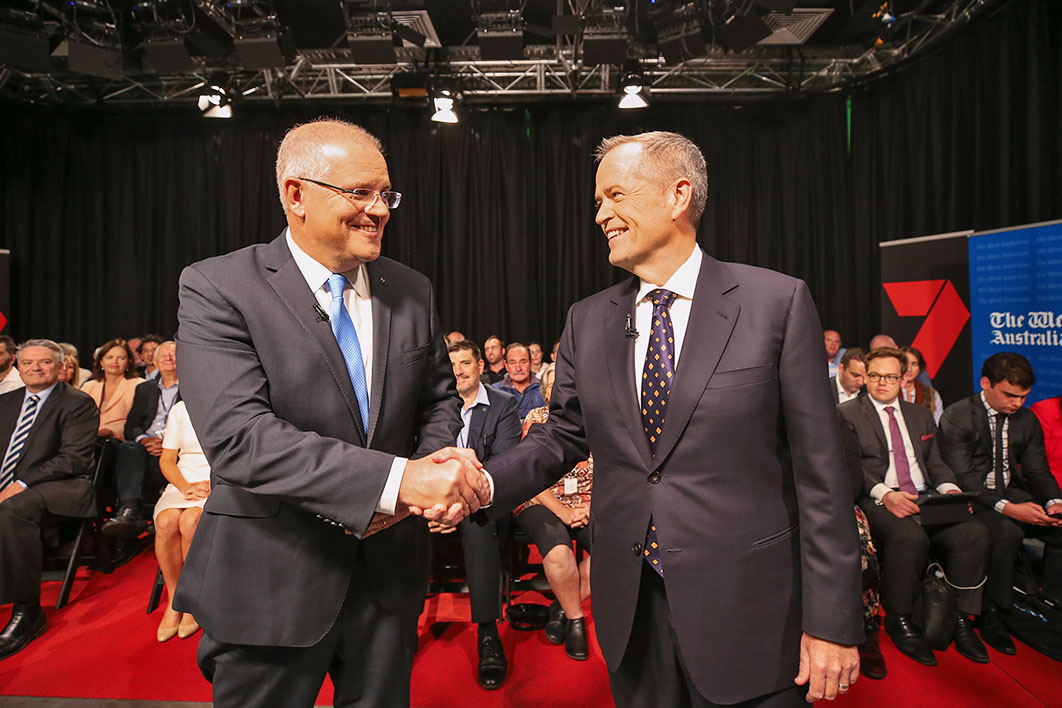

Channel 7’s Mark Riley came straight to the point with the first question at the leaders’ debate in Perth on Monday.

“What will you do to restore faith and trust in the political system?” he asked. Scott Morrison responded by running on his record, including the change to the Liberal Party’s rules that makes it harder to change leaders between elections — an unintended admission that he would not have been in his job under a better system.

He also referred to what he called “demonstration of performance” — stopping the boats as immigration minister, just as he promised he would; reducing welfare dependency as social services minister; bringing the budget back to surplus as treasurer; and, for the locals, giving Western Australia more GST revenue. A few details were overlooked, such as the Coalition’s promise before the 2013 election to eliminate the surplus, which remained in deficit when Morrison was treasurer, and still is; but let’s not be too pedantic.

Bill Shorten promised a national anti-corruption commission as a down payment on rebuilding trust in institutions. And he also suggested that Labor was “trusting the Australian people with our policies” by being upfront about “what we want to do and how we’re going to pay for it.”

All in all, you could call it one very small step for democracy. With their occasional outbreaks of civility, both leaders also conceded indirectly that the problem of trust goes much deeper. Mind you, this only occurred under duress, such as when they were asked what they admired about each other. (Morrison nominated Shorten’s public service; Shorten proffered Morrison’s stance on mental health and that he was “a man of deep conviction.”) The audience, perhaps overcome with relief that the pollies were not slagging off at each other, applauded.

Of course it won’t last. Politics has always been a winner-takes-all blood sport and increasingly it has become a no-holds-barred contest. There was a slight reprieve in the last election, when Malcolm Turnbull tried to accentuate the positive and was relatively restrained in his attacks on Labor — the operative word being “relatively.” Labor responded with Mediscare, the spurious claim that a re-elected Coalition government would privatise Medicare. It is now received political wisdom that this is what brought Labor to the brink of winning the election, though the evidence is less clear.

The Liberals certainly aren’t observing the niceties this time. In the first week of the campaign, 93 per cent of Liberal advertisements on Facebook were negative, according to the Australian National University’s Andrew Hughes, although there has been a shift to more positive messaging since. Among the more dubious is a Liberal advertisement that tries to outscare Mediscare — a claim, without evidence and despite Shorten’s repeated denials, that a Labor government could introduce death duties.

Both sides of politics are well aware that voters hate negative advertising. But they have increasingly used it in recent decades because they are convinced it works, though this is a view that has come under challenge more recently. What is not in doubt is the corrosive long-term impact of negative campaigning. If you start with a degree of voter scepticism about politics, reinforce it with the spectacle of politicians attacking each other, double down by imputing the basest of motives to your opponents, and then add in some false claims, is it any wonder that voters’ opinion of politicians is at a low ebb? It certainly is not an approach that, in Morrison’s terms, values public service.

In this descending spiral, negative campaigning increasingly turns people off politics, leading politicians to become increasingly strident in their desperation to catch attention, alienating voters further… and so on. This has landed us where we are today, with parties complaining how hard it is to get their messages across.

In 2007, a Democracy 2025 survey found that 86 per cent of respondents said they were satisfied with how democracy worked in Australia — a high point in recent times. By 2013 this had fallen to 72 per cent and since then it has dropped off the cliff, plunging to 41 per cent last year — and that was before the Liberals’ coup against Malcolm Turnbull.

All kinds of factors may be bound up in this precipitous fall, ranging from the collapse in trust in institutions generally to the international reverberations from the chaos of Brexit and the toxic presidency of Donald Trump. Nor is it just the politicians who are to blame in Australia. Mainstream and social media amplify negative political messages, while many voters never get around to serious consideration of policy.

This election may be the ultimate test of whether policy reform is still possible in Australia or if, rather, virtually any proposal for change can be torpedoed by a scare campaign. Though Labor’s policies are often presented as radical, in truth they are mostly cautious and limited. Ending a tax refund for people who do not pay any tax and paring back one of the most generous negative-gearing tax concessions in the world (and grandfathering the old system) are not revolutionary proposals, except within the tight boundaries of what is possible in politics these days. They are nowhere near as far-reaching as the Fightback! package that John Hewson took to the “unlosable” election in 1993, which was won by Paul Keating.

Labor’s defeat in this election would instantly be interpreted as a verdict on these issues and it would guarantee that no policy reform of any substance would be advanced in the foreseeable future. Some may argue that future governments would still be able to make changes once in office. After all, most of the major economic reforms of the Hawke government were not taken to voters beforehand. But it was the formidable sales skills of Keating and Bob Hawke that entrenched those changes and, even more importantly, they mostly had the support of the opposition. It is hard to envisage such a combination in the current climate.

Last year’s Democracy 2025 survey canvassed attitudes to a series of reforms aimed at rebuilding trust. The themes that emerged most prominently were greater integrity, transparency and accountability in the political system, together with more voter involvement.

Placing limits on election donations and campaign spending gained the strongest support. Some restrictions apply now but, to the extent that people know about them, they seem conscious of how ludicrously inadequate the existing measures are, particularly at the federal level.

There was also strong backing for the proposal that “public services should be co-designed with Australian citizens,” for the recall by local voters of MPs who are not performing, for free votes in parliament, for citizen juries to help solve complex policy problems, and for ordinary party members and voters to have more say in choosing party leaders and election candidates.

Some of the proposals may be challenging to implement in practice. There will certainly be resistance from the political establishment. But if politicians are to have any hope of getting voters to listen to them, let alone persuading them of the merits of their policies, the strong sentiment behind these reforms will need to be acknowledged and acted upon. •