Last week, watchers of Australian politics were treated to a curious spectacle.

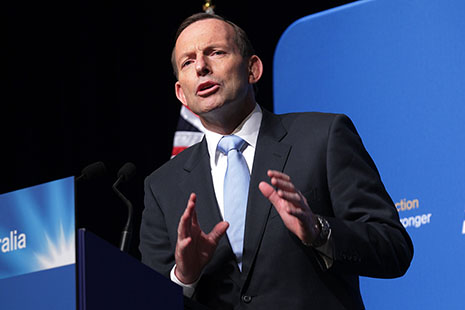

It was late on Thursday, just before the House of Representatives adjourned. The Abbott government’s eleven carbon-price repeal bills had passed the chamber and Liberal members rather self-consciously gathered to enact a ritual of high fives, hugs and pats on the backs. As you can see, some smiles looked a little forced.

The same bills, in slightly different format, had got through the House back in November, but been rejected in the Senate. They still have to get through the Senate (and probably will). So it seemed a rather empty performance. Who was it for? How many Australian households erupted in celebration on seeing this snippet on the nightly news?

When the Gillard government’s carbon bills became acts it late 2011, Labor’s popping corks were also incongruous, but for different reasons. Most Australians didn’t want the bills to go through because they feared what it would do to them, and to the economy, and resented the prime minister’s “broken promise.”

The political power of the “carbon tax” has been an integral element of Australia’s political narrative for the more than three years since Julia Gillard announced it in February 2011. But the story and the reality separated long ago. Now, two years after it came into operation, it is a fourth-order issue in voterland, if that.

When opinion pollsters ask Australians if the Labor opposition should allow the government to abolish the “carbon tax,” they tend to respond in the affirmative. After all, it was a high-profile promise taken to last year’s election. But when surveyed about their own policy preferences, their responses are susceptible to how the question is worded.

Last weekend, Essential Vision asked, “Which of the following actions on climate change do you most support?” Of the four-in-five respondents who chose one of the available options, 41 per cent opted for “Dumping the carbon tax and not replacing it at all.” At the other end of the spectrum, “Replacing the carbon tax with the Liberal’s ‘direct action’ plan” got just 11 per cent support.

In between were “Keeping the carbon tax” (20 per cent) and “Replacing the carbon tax with an emissions trading scheme” (27 per cent), or a combined 47 per cent favouring a price on carbon and 52 per cent in favour of “direct action” or nothing. (Due to rounding the numbers add to 99, not 100.) Maybe that’s a dead heat.

Now, the vast majority of Australians would have trouble describing the difference between the “carbon tax” and an emissions trading scheme, or ETS. (Answer: it’s mostly semantic; Kevin Rudd’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, or CPRS, was an ETS with a one-year fixed-price period; Gillard’s an ETS with a three-year one.) If it was left untouched, the “carbon tax” would become a fully fledged ETS in July 2015 anyway.

A post-budget survey by Reachtel found majority support for a vague description of the government’s deficit levy, and a week later the same company found most respondents preferring “a price on carbon for companies with high emissions” to “the proposed deficit levy” as revenue raisers. As I said, the phrasing of the questions matters. Figures like these can be interpreted in several ways. But evidence for hatred of the “carbon tax,” much less of carbon pricing, can’t be found.

A large amount of mythology has also evolved about the Rudd government’s April 2010 decision to dump its long-cherished CPRS. Most commentators seem to assume it was unpopular at the time – otherwise why walk away from it? Only weeks after the announcement, though, a Nielsen poll found 58 per cent support for “an emissions trading scheme for Australia.”

Earlier that year, in February, Newspoll had a majority, though definitely a shrinking majority, supporting the CPRS. (The shrinkage was assisted, no doubt, by the Coalition’s changed position, and probably by the prime minister’s now slowly-deflating bubble.) A month further back, though, an Essential poll had validated what the parties’ qualitative research was no doubt finding: that when the pollsters pointed out that a price on carbon would increase the cost of energy, and if they used the word “tax,” support could turn into apprehension.

The importance of climate change to Australian politics has been an article of faith among the commentariat since 2007, but its impact has probably been overstated. Or it’s been indirect – as it was in 2010, when a politically timid prime minister and a hollowed-out party machine, using market research as a crutch, produced a political malfunction.

In his final year as prime minister, John Howard was persuaded to feign an eagerness to act on climate change. He promised an emissions trading scheme, and even insisted that Australia would go it alone if necessary. It may or may not have been the wisest course of political action.

At least some of his allies would undoubtedly have been advising Howard to go the other route and warn of the devastation that would befall the country if Labor enacted its irresponsible, complicated and costly scheme. Perhaps the former PM occasionally lies awake contemplating the road not travelled.

It’s generally accepted that the CPRS brought down Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership two years later, but the dire state of the opinion polls, week and fortnight in and out, was at least a necessary condition for that spill. Had Turnbull appeared at all likely to take government the following year, the Liberal party room would probably have tolerated his enthusiasm for pricing carbon – at least until they were in government – as they had tolerated Howard two years before. And if it hadn’t been climate change that did him in it might have been something else.

Then came Tony Abbott. Notwithstanding the public’s fading enthusiasm for acting on climate change, the Coalition’s scare campaign against the CPRS would probably have failed. Scare campaigns work for governments but not usually for oppositions; their core theme is fear of the unknown and their chief object is to create uncertainty about what the (by definition) untried and inexperienced opposition might unleash if given power.

The most effective scare campaign in recent memory, Paul Keating’s in 1992–93, worked not just because the Liberals’ proposed GST wasn’t popular; that policy became an emblem of all manner of things that were worrying about opposition leader John Hewson. Keating’s often undignified ranting, like Howard’s in 2001, didn’t damage his image too badly because he had the institutional force of incumbency behind him.

A wide-eyed opposition leader, screeching fire and brimstone – like Abbott in early 2010 – is a different commodity. The louder they shout the more difficult they become to vote for. But in the end the Rudd government called its own bluff. Then, on 24 June of that year, it went one better and threw away incumbency itself.

The following year, as prime minister, Gillard introduced a scheme that she disastrously allowed to become known as a “tax” and a “broken promise.” (It did represent a broken promise, but not the one most people believe, and it was something the Greens forced her into doing.) The scheme was widely reviled and feared until its introduction in July 2012, after which most Australians gradually got used to it and, perhaps, started wondering what the fuss had been about.

Last year the reborn Kevin Rudd’s dramatic announcement that he would “terminate the carbon price” (he meant that he was bringing forward the shift to a floating price from July 2015 to July 2014) was dumb politics: a counterproductive capitulation to the Coalition’s preferred terminology, which continues complicating Labor’s public position to this day. In other words, it had Sussex Street’s fingerprints all over it.

Now, as we enter the new Senate term, our political storytellers continue insisting the “carbon tax” was important to last year’s election result. It has to be – we’ve all been obsessing over it for so long. The tomes have been printed and distributed and cannot be pulped.

In reality, most people voted for change last September because they believed the Labor government was incompetent and, most importantly, its spending was out of control. Now it’s in government, the Coalition has stopped claiming that abolishing the carbon price would end all the country’s ills. Now it’s simply a way of cutting the price of electricity.

When asked, a majority of Australians still say they want some sort of action on climate change, with direct action the least-favoured of the suggested plans. That doesn’t mean it’s an election-decider. Fury at the carbon tax, and desperation for its repeal, is restricted to a small minority of cultural warriors and rusted-on Coalition supporters.

But someone forget to tell the Abbott government. Either that or they were dancing for their own entertainment. •