Democratic Adventurer: Graham Berry and the Making of Australian Politics

By Sean Scalmer | Monash University Publishing | $39.99 | 349 pages

The struggle for democratic reforms in pre-Federation Australia largely avoided Europe’s mid-nineteenth-century civil commotion bloodshed, and its repressive aftermath, but was nonetheless intense, protracted and played for high stakes. Curiously, Eureka aside, the struggle largely took place within the confines of that powerful democratic symbol, parliament.

The battlelines were already taking shape before self-government began arriving in the Australian colonies mid century. An early governor of Tasmania, for instance, urged his political masters in London to adopt a bicameral legislature because the “essentially democratic spirit which actuates the large mass of the community” would need to be kept in check by an appropriately elected upper house.

The governor proved to be on the winning side of the argument, and the colonies were each given an upper house. Of course, views like his were never paraded as justification for that brake on popular democracy. Rather, upper houses were dressed up as sober and responsible mechanisms to guard against the hasty legislation that popularly elected chambers were thought likely to embrace.

The ensuing battle between popularly elected lower houses and conservative upper houses — either appointed or elected on a restricted franchise — characterised much of a democratic struggle that lasted well into the twentieth century. In Queensland, a prolonged struggle saw an obstructive Legislative Council abolished in 1922. Elsewhere, less dramatic reforms centred on creating genuine houses of review rather than obstructionist chambers.

Our political historiography has perhaps focused too little on the pre-Federation era as an important, if unacknowledged, intellectual seedbed for subsequent developments. In Democratic Adventurer, however, Sean Scalmer rescues a key figure of that time, Victoria’s Graham Berry, from relative neglect, deftly and forensically examining his colourful career within the larger context of democratic reform.

Three times premier of Victoria, Berry was the most controversial political figure of his age, admired by his supporters and loathed by his opponents. He is credited with forming Australia’s first real political party and remembered for his American-style stump oratory. He might well be, as Scalmer argues, the real father of the powerful protectionist movement that so shaped the early Commonwealth — an accolade usually bestowed on newspaper proprietor David Syme, a sometime ally and sometime harsh critic of Berry.

London-born, Berry never lost his working-class accent — a feature often mocked by his middle-class opponents. On one occasion in the Legislative Assembly, he is said to have asked the speaker what was “before the ’ouse,” which prompted an interjection of “an H.” According to Alfred Deakin, who greatly admired him, Berry left school at eleven and was apprenticed as a draper, but also became something of an autodidact, forgoing pleasures to buy books on a variety of subjects and even concealing himself under a staircase to read Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Berry landed in Melbourne in 1854, accompanied by his wife, Harriet, and their three children (another eight would be born in Australia). Unlike most other arrivals, they were not attracted by the gold rush; instead — at least according to some evidence — Berry was fleeing a scandal arising from a sexual indiscretion, a failing that would recur in Melbourne. It was, writes Scalmer, “a public life in which the private realm would periodically intrude; Berry struggled to keep it out.”

Setting himself up as a respectable grocer (and occasional sly-grog merchant) in the inner-eastern suburb of Prahran, Berry prospered. By the 1860s, when the family home was offered for sale, he and his wife owned a “superior wooden house” of five ground-floor rooms, a servant’s room and stables, as well as several other properties in the increasingly affluent area.

Melbourne was beginning to prosper too. A mechanics’ institute was founded in Prahran and the government financed the construction of a new building for reading and discussion. A courthouse was built and a building society formed. Residents grouped together in a reform association, assembling to debate the prospects of local self-government and seek additional state support.

At the forefront of these initiatives was Berry, who had argued for the formation of the reform association as “the only real mode of redressing the public grievances.” He acted as the organisation’s inaugural secretary and sat on the management committee of the mechanics’ institute. In 1855, he advocated for the immediate incorporation of Prahran as a municipality and took a prominent part in Victoria’s first parliamentary elections.

Civic-minded he was, to be sure, urging his neighbours to “show a little more enthusiasm” for public welfare. But, consistent with the ambiguity that would characterise his later career, Berry’s arguments for greater public infrastructure rested partly on the “immense advantages” that would accrue to existing property owners (“property would be infinitely more valuable”).

Berry sought election several times to the Prahran Council, but was unsuccessful. An opponent claimed it was because he could not get anyone to trust him. A similar story attached to two early attempts to win a seat in parliament. In one contest, for the electorate of South Bourke, which included the affluent suburb of Hawthorn, his Trinity College–educated opponent, a lawyer, mocked him as “a gentleman, he believed, in trade at Prahran.” In his concession speech, Berry railed against “the snobbery of the upper classes.”

Having then moved across the river to sprawling Collingwood, a shantytown of tents and simple dwellings, he purchased the local newspaper, the Collingwood Observer. Seeking admission to the parliamentary press gallery, his way was blocked on the grounds that he represented merely a suburban newspaper, not a paper of record. As Scalmer writes, “Graham Berry did not belong.”

The Observer provided a political platform that Berry augmented with outdoor platform speaking, honing his salesman’s gifts of eloquence and persuasion. “He talks remarkably well and fluently,” one opponent observed. “There is no doubt he speaks in a very earnest manner, so that he leads his hearers to think that he believes what he says.”

Eventually, Berry — described by the conservative Argus as “an extreme liberal” — was elected to the Legislative Assembly for East Melbourne at a by-election in 1861. At the general election later in the same year he switched to the seat of Collingwood, where he was re-elected in 1864 but defeated in 1865.

Along with his newspaper and public speaking, Berry soon realised the need for a broad organisation to carry his political message and mobilise the masses. The result was the formation of the first mass political party, the Australian Reform and Protection League. Moving to Geelong, he started a newspaper, the Geelong Register, as a rival to the Geelong Advertiser. He returned to parliament as member for Geelong West in 1869, later switching to Geelong, holding office in two governments as a convinced protectionist, and steering a bill for increased tariffs through the parliament.

By now the debate about the powers of the Legislative Council was raging, with democrats pointing to the fact that it was elected on a franchise that encompassed less than one-tenth of the lower house and had powers to originate, alter and reject any legislation apart from appropriation or taxation bills, which it could reject outright. To Berry and his fellow liberals, the privileges and intractabilities of this chamber were anathema: its membership was dominated by a “squatting” class that had seized land from Indigenous people, secured the legal recognition of that seizure, and quickly amassed wealth and high position through pastoralism.

This situation would soon escalate into crisis, but before then Berry’s private life was again in focus. Something had already seemed amiss in his business affairs, notably a questionable goldmining project in Collingwood and the jailing for fraud of his business partner in Geelong. After the death of his wife in 1868, and with a large family to look after, he married Rebekah Evans, a teacher three decades younger than him, in 1872. The couple would have seven children.

As treasurer, he was accused of appointing his father-in-law to a well-paid government job — merely the first known instance of his nepotism. A committee of inquiry heard further evidence suggesting amatory indiscretion and concluded that the appointment of his father-in-law was a case of “personal immorality.” The government fell a few days later, and Berry’s future looked decidedly uncertain.

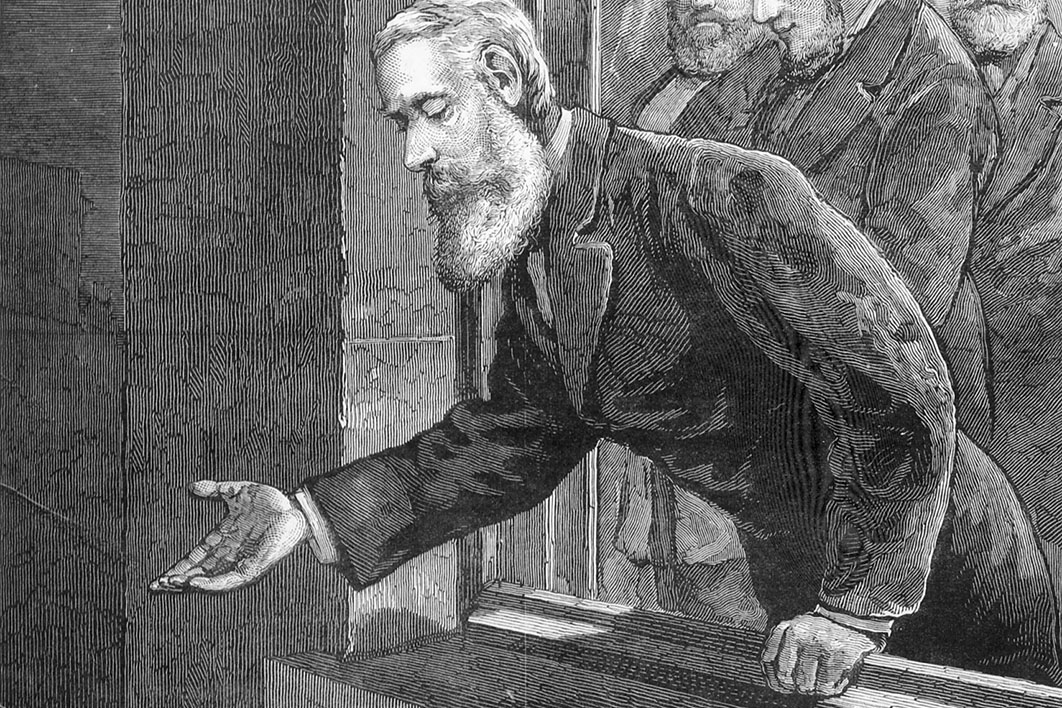

But within three years Berry was premier, serving the first of three terms. In the second, he moved to implement a land tax bill opposed by the Legislative Council. His opponents there threatened to retaliate by blocking supply, especially in relation to the payment of MPs — a move aimed at those without private means. That decision led directly to the crisis known as Black Wednesday — 9 January 1878 — when Berry’s government dismissed around 300 public servants, including department heads, judges and senior officials, after the Legislative Council blocked the bill.

This was a point of high drama in the broader struggle between the Berry ministry and the Legislative Council that gripped Victoria between 1877 and 1881. Officially, the retrenchments were justified on the grounds of financial exigency, but another consideration was the government’s desire to penalise those senior officials who supported the Council. Although a visit to London failed to resolve the dispute, a compromise of sorts was eventually reached, at least in the extension of payments to members.

Berry went on to serve a term as agent-general in London, returning to politics briefly in the 1890s. His legacy ensured the championing of protectionism, most notably by his young follower, Alfred Deakin. It also put democracy and its necessary struggles on the political agenda.

But he should be remembered for more than that. Scalmer shows how Berry used his considerable oratorical skills to both rouse supporters and frame complex issues. His organisational skills paved the way for later parties.

Dickensian throwback, a cad and a bounder, and a chancer with a quick eye: Berry was all of these things, but his democratic credentials remain untarnished.

Sean Scalmer has written a richly detailed account of this now-distant figure. His finely nuanced explication of complex issues — private and public — opens a fascinating window on an age that was decisive in shaping Australia’s future. For all his flaws and failings, Berry had an undeniable influence on the course of Australian politics; he was in every sense a democratic adventurer. •