This Saturday we’ll be a year out from the next Victorian election. But if two opinion polls released in recent days are any guide, you can call the result now: despite everything, they report, the Andrews government is on track for a second landslide win, as big or bigger than in 2018.

Ignore all the frustrations bursting out on the streets of Melbourne, on talkback radio and on the letters pages of Murdoch’s Herald Sun — and right now, of the Age as well. The polls tell us that if an election were held today, Victorians would re-endorse the man the Murdoch empire calls “Dictator Dan” with a thumping majority.

Newspoll reports that polling last week found Victorians would have re-elected Labor with a two-party vote of 58 per cent to the Coalition’s 42 per cent. That’s effectively unchanged from the 57.6 per cent Labor won in its landslide victory in 2018.

Another poll a week earlier by the Roy Morgan group reported an identical two-party split — although 15 per cent said they would vote for micro-parties or independents, compared with just 9 per cent in the Newspoll. Morgan’s figure sounds more plausible.

The Coalition scored 36 per cent of first preferences in Newspoll, but only 31 per cent in the Morgan poll. Labor got 44 per cent in Newspoll, 43 per cent in Morgan, and the Greens an unchanged 11 per cent in both.

Really? So two of the most tumultuous years in Victoria’s recent history have left the electorate unmoved? So unmoved it proposes an exact replica of the status quo?

To outsiders, that sounds implausible. On almost every count, Victoria has had the worst outcomes of any Australian state during the pandemic. It has 26 per cent of Australia’s population, but 66 per cent of all Australian deaths from the disease. It was home to 58 per cent of all the people infected in Australia: more than 110,000 of them, one in every sixty people in the state.

And to try to contain the virus, Daniel Andrews made Melbourne the most locked-down city in the world: for eight of the past twenty months, shops and schools were closed, and people required to stay at home except for a handful of reasons. You’d think that surely wasn’t a policy the voters warmed to — and when Melbourne alone, even now, is still developing 1000 new cases a day, it clearly failed to meet its objectives.

Not surprisingly, Victoria also suffered the worst economic costs. Last week the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that Victoria’s economic activity has shrunk more than that of any other state.

In the year to June 2021, Victoria’s real output per head was 2.25 per cent lower than it was two years earlier. Adjusted for inflation, spending by households and business fell 7 per cent over the two years. Only the stimulus of a 13 per cent jump in government spending kept the slump from being deeper.

The Victorian economy has suffered real damage. Only time will tell how well it can recover, but it’s optimistic to think Melbourne will go back to being the same as it was before the lockdowns.

Yet if the polls are right, none of this has turned Victorians against Labor.

Perhaps that’s to be expected. In our part of the world, every government facing the voters since Covid arrived has been comfortably returned: in New Zealand, Queensland, Western Australia, Tasmania, the ACT and the Northern Territory.

But in 2022 the election outcomes could be less friendly to governments. The Morrison government has been trailing in most recent polls; the bookies have now installed Labor as favourite. The Marshall government in South Australia is no certainty to be returned in that state election on 19 March. And there are other signs that the Andrews government’s grip on power could at least be loosened when Victorians go to vote again.

For Matthew Guy, the ebullient forty-seven-year-old conservative who returned as opposition leader two months ago by successfully challenging Michael O’Brien, there’s no good news in these numbers. But Guy is an optimist by nature, and he will find other reasons for hope.

First, he has been here before. He was opposition leader in June 2017, when the Herald Sun headlined: “Victorian voters would dump Andrews government today, Galaxy poll shows.” Galaxy, a stablemate of Newspoll, reported that the Coalition was trouncing Labor by a 53–47 margin. A year and a half later, however, in the real election, Labor trounced the Coalition by 57.6 to 42.4 (adjusted to include Richmond, which the Coalition didn’t contest). In other words, polling this far out is not a reliable guide to the election outcome.

Second, while no poll in Victoria since 2018 has shown the Coalition ahead, other polls in recent months have suggested some movement its way. Two polls published when Melbourne was locked down again in June reported swings of around 6 per cent: not enough, but close to what it needs to get. A Resolve poll published in the Age in October failed to provide any figures for the two-party vote, but it implied a small swing the Coalition’s way.

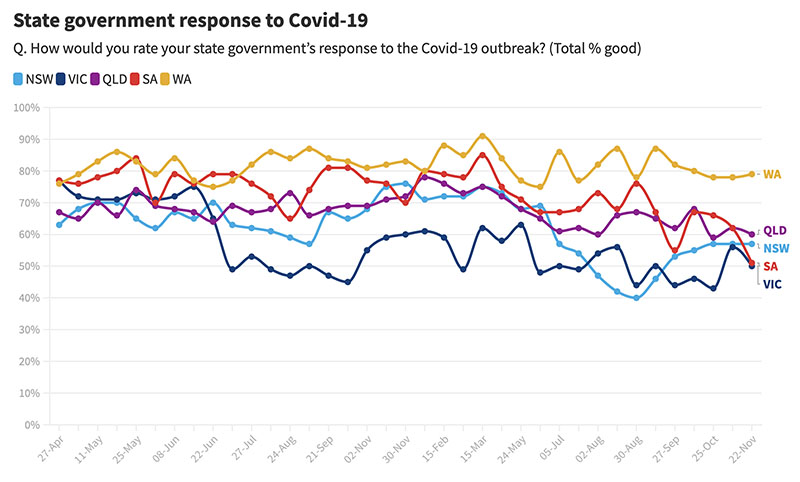

Polling on state voting intentions is irregular, but Victorians have a decent proxy in the Essential Report’s frequent polling for the Guardian on what voters think of their state government’s handling of Covid-19. While the numbers bounce up and down depending on lockdowns, the Victorian government has consistently ranked last since July 2020, except for a few weeks in August and September when Sydney’s outbreak hit its peak.

In the second half of 2021, on average, only 49 per cent of Victorians thought their government had done a good job of handling the crisis. That compares with 51 per cent of voters in New South Wales, 63 per cent in Queensland, 65 per cent (but sliding) in South Australia and a stellar 81 per cent in Western Australia.

Source: Essential Report

On those figures, you wouldn’t expect Labor to get back with its majority intact. As the fourth wave now sweeping western Europe reminds us, a lot can happen in a year, and it can be unpredictable and uncontrollable.

Scott Morrison and his government are lead in the saddlebags of the state Liberals: Newspoll’s federal voting averages for the September quarter reported a 5 per cent swing to Labor in Victoria. Matthew Guy might be secretly hoping they lose office in May, so that by November any animosity towards the federal government will hurt Labor, not his team. Daniel Andrews might retire. Anything could happen.

Third, the timing of these polls didn’t help the Coalition. While they were being taken, the anti-vax street protests, with their extremist language and props — those notorious nooses and death threats directed at Andrews — virtually shoved mainstream voters in Labor’s direction, especially when some Liberal MPs featured as speakers.

To some extent, that was offset by Andrews’s authoritarian pandemic bill, which allows the premier to bypass parliament and normal legal processes during a pandemic. That certainly risks alienating voters who care about civil rights and the importance of having checks and balances to prevent governments misusing their power. But Essential’s recent finding that even 62 per cent of Coalition voters “strongly oppose” the anti-lockdown protests could cancel out fears about the government having too much power.

But the most important reason to take the polls with a grain of salt is that Andrews’s recent decisions to end the lockdown, open the borders and remove most restrictions — even before new cases had begun to turn down, and long before Victoria was out of trouble — suggest strongly that he was feeling under pressure, probably above all from his pollsters.

Melbourne exited lockdown when the state was recording 2000 new cases a day. A year ago, the Andrews government wanted lockdowns to continue until there were fewer than five new cases a day. Even now the state is still averaging more than 1000 new cases a day.

Andrews argues that the state’s high vaccination rate — 89 per cent of those twelve and over are now double-dosed — means opening up no longer carries the same risks. True, and it’s important to remember that vaccinations protect us from death and serious illness better than they protect us from infection. But Europe’s experience is salutary: countries with highly vaccinated populations such as Germany, the Netherlands and even Denmark are now experiencing bigger outbreaks than ever before. Whatever Andrews says, I’ll bet his decisions to open up were not based on medical advice.

Given Labor’s complete dominance of the Victorian scene, there has been little interest in the redistribution of state electorates, finalised late last month. Victoria’s state redistributions are usually done much better than the federal ones, and the latest is no exception.

It boldly takes the axe to no fewer than three electorates in the middle southeastern suburbs — Ferntree Gully (Liberal), Keysborough and Mount Waverley (both Labor) — to create new seats in the outer southwest, northwest and southeast (all Labor). It also bites the bullet to fix one of the anomalies of the past, by bringing all the Latrobe Valley towns into one seat (Morwell), which increases the odds that Labor will win it back from independent Russell Northe.

All up, Antony Green estimates that Labor would notionally gain two seats, one from the Liberals and one from Northe, giving it fifty-seven seats in the eighty-eight-member parliament. The Coalition would drop to twenty-six (twenty Liberals, six Nationals), the independents would drop to two, and the Greens would remain on three.

Our friend Antony further estimates that of the twenty-six Coalition seats, nine are held by 1 per cent or less, and fifteen by 5 per cent or less. That puts the Coalition very much on the defensive, and in a weak position to launch an attack.

On the other hand, a uniform swing of just 6 per cent against Labor would cost it its majority, leaving it with just forty-four of the eighty-eight seats. While the Liberals and Nationals would require an implausibly large swing to win office, it is just plausible that if things go their way in 2022, they could push Labor into minority government. But they’re a long way from that now.

One key issue that will come to a head in the last months of this parliament is the future of the voting system for the Legislative Council. Will Victorian Labor continue with the system that allows voters’ preferences to be decided by backroom deals between the parties?

In Western Australia, Labor is now moving to abolish “group ticketing” after this year’s state election saw the Daylight Saving Party win a Legislative Council seat with just ninety-eight votes. That will make Victoria the last jurisdiction in Australia that has yet to reform a system that denies voters the right to decide their own preferences.

One assumes the original aim of the major-party bosses was to give themselves the power to decide voters’ preferences. But as micro-parties have mushroomed, the system has been taken over instead by the “preference whisperer” Glenn Druery. He has made an art form of working out deals that allow micro-parties to win seats with tiny votes by directing preferences to each other — no matter how remote they are ideologically.

At the 2018 Victorian election, Druery excelled himself by delivering his clients nine of the forty seats in the Council. At the time, he was working for Derryn Hinch, so Hinch’s Justice Party won three seats with just 3.75 per cent of the vote, whereas the Greens — excluded from Druery’s system — won 9.25 per cent of the vote but ended up with only one seat.

In the Eastern Metro seat, the Greens with 9 per cent of the vote lost out to Transport Matters with 0.6 per cent. In Southern Metro, the Greens’ 13.5 per cent was defeated by Sustainable Australia’s 1.3 per cent.

The system cost Labor itself a seat in Northern Metro when Fiona Patten, co-founder of the Reason Party, organised her own preference swaps to upstage both Druery’s team and Labor. The Coalition lost three seats it would have won had voters been allowed to direct their own preferences, and the Greens between two and five.

Even with its landslide 57.6 per cent of the two-party vote in the lower house, Labor could win only eighteen seats in the forty-member Council. Still, with eight separate minor parties with whom it can deal issue by issue, it has found the Council malleable to its wishes until now. But its failure to consult most of them over the pandemic bill left it vulnerable when disgraced Labor powerbroker Adem Somyurek, after a long absence, decided to return to the Council to cast his vote against giving Andrews any more power.

Negotiations on the bill are now proceeding with the previously ignored micro-parties, through gritted teeth on both sides. It must focus Labor’s mind on reform of the voting system. The Liberals and Greens, who combined to push through the federal reform in 2016, would be willing partners. But you would not expect Labor to show its hand until as late as possible, since it still depends on the minor parties to pass its legislation.

The Greens and the Coalition were the main losers from Glenn Druery’s artwork last time. But if Labor does lose ground next year, it could become the main victim. A 5 per cent swing in Council voting could cost it as many as five seats, making the upper house almost unmanageable.

Difficult as Labor and the Greens find it to cooperate in Victoria, where they fight an endless war for control of inner Melbourne, it would be in their mutual interest to change to a voting system that allows the voters to decide their own preferences, and stop Glenn Druery doing it for them. •