Australia’s international development minister, Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, found herself in a fix last week after she claimed that China’s aid in the Pacific produced “useless buildings” and “roads to nowhere” while “duchessing” politicians. Australia’s relations with China, already at their lowest ebb in years, took another blow, and Xinhua News’s Canberra correspondent bestowed on Australia the title of “arrogant overlord” of the Pacific.

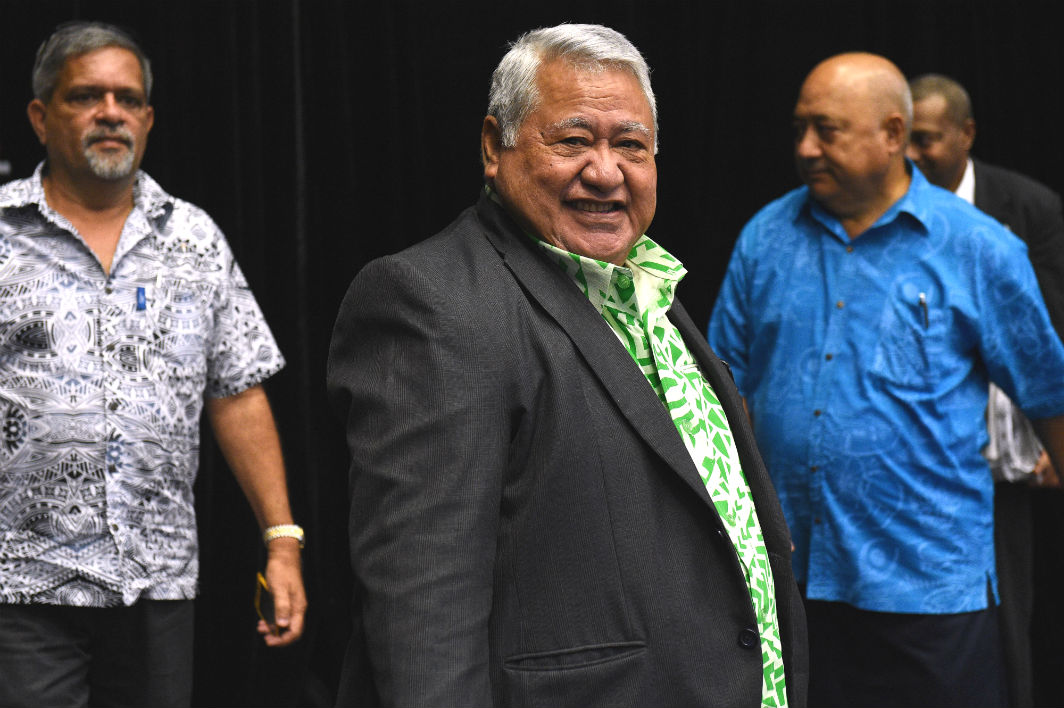

In the region itself, Samoan prime minister Tuilaepa Sailele suggested that the minister’s remarks could “destroy” Australia’s relationship with island nations. He zeroed in on China’s willingness to provide aid to deal with the impact of climate change. The media director of the Vanuatu Daily Post noted that while “we are right to question the design, implementation and price of some of these projects… these roads are not ‘roads to nowhere.’ They lead to our homes.”

Where did the senator’s remarks come from? What is fuelling the differences opening up between the Coalition and Labor on our relationship with China, quite at odds with the Liberal Party’s traditionally pro-business ethos?

A hint came in an opinion piece by Maurice Newman, former chair of the ABC, the ASX, the Australia–Taiwan Business Council and the government’s now-defunct Business Advisory Council. Writing in the Australian earlier this month, Newman revealed that his expertise extends beyond his well-known conspiracy theories about the Bureau of Meteorology, and takes in China’s engagement with the Pacific. The title of the piece — “China Emerges as All-Powerful New Deity in Pacific Cargo Cult” — gave an inkling of what was to follow.

Newman may not have chosen the headline — or the accompanying cartoon, which features a huge panda ready to devour an uninhabited Pacific island — but he went on at length about cargo cults, a term that no credible anthropologist still uses. In fact, I first heard about Newman’s article when one of my doctoral students emailed me to protest that “‘cargo cult’ belongs in the savage slot that anthropology disowned decades ago. No serious anthropologist uses the term anymore.”

Beyond hurting the feelings of anthropologists, though, the piece might reveal where Senator Fierravanti-Wells’s thinking on the Pacific and China comes from. The most striking thing is that Newman’s Pacific is terra nullius. No Pacific Islanders are quoted in an article purporting to be about their welfare, save for Kiribati’s “President Anote Tong,” who is scolded for daring to suggest that his island is sinking like the Titanic. Alas, Newman can’t even get this right.

Tong is the former president of Kiribati, and the incumbent, Taneti Maamau, used the Titanic analogy to convey more or less the opposite, in a YouTube address launching Kiribati Vision 20. “Climate change is indeed a serious problem,” Maamau said. “But we don’t believe that Kiribati will sink like the Titanic ship. The Titanic ship is different. It is built by human hands whilst our country, our beautiful islands are created by the hands of God.”

Where it does appear, Newman’s Pacific is home to passive folk ripe for exploitation by Leninist China, which has “de facto colonialism” as a “probable objective.” We aren’t given a percentage on this, but under the spell of the cargo cult (which seems to apply to the entire South Pacific), “the people of the Pacific are very open to seduction.”

Similarly, in Fierravanti-Wells’s world, Pacific politicians are “duchessed.” This wonderful word suggests that flattery and a top-notch banquet are enough to make Pacific elites sign over anything. But portraying the Pacific’s leaders as passive, corrupt and slightly dim is probably not the best way to win them over.

We’ve been here before. A 2006 Senate report, China’s Emergence: Implications for Australia, had an entire chapter dedicated to warning of the dangers in the southwest Pacific. Analyst after analyst after think-tank expert lined up to warn that China was “going for the jugular” with “lavish banquets” targeting “tiny, fragile Pacific states.” Many of the experts were from the Centre for Independent Studies, of which Newman was a founding member.

Underprepared Chinese aid contractors find the Pacific far from passive. China Jiangsu International saw its workforce in Port Moresby robbed twice in two days when locals discovered it had no security guards watching over the construction site for the National Convention Centre in Waigani. The management of China Shenyang International Economic & Technical Co-operation Ltd begged nearly every other Chinese contractor in Papua New Guinea to take over their Pacific Marine Industrial Zone project. Far from the company benefiting from the A$196 million project, it was local spivs who profited, receiving such vastly inflated payments as four million kina (A$1.5 million) for a gate.

Newman sees China’s presence in the Pacific as monolithic and entirely controlled by Beijing. While he is right that China under president Xi Jinping is a different proposition from that of the Deng Xiaoping era, to conclude that “the emergence of a more assertive, Leninist China means all bets are off” is an astonishing leap, particularly for a leader of the Australian business community.

While much of China’s own propaganda would like you to believe Beijing calls the shots, the reality in the Pacific is far from Newman and Fierravanti-Wells’s vision. The Chinese government has little sway over what happens there. It simply lacks the personnel to oversee aid projects, leaving the field open to Chinese companies, their subcontractors and their Pacific partners, who reverse-engineer projects for approval by China’s Export-Import Bank.

While there is no shortage of white elephants to show for Chinese companies’ work — my own favourite is a seldom-used aquatic centre outside Apia whose mascot was a white elephant, hastily repainted yellow — Pacific leaders are more discerning buyers than they were in 2006, when China unveiled its first round of concessional loans. Even in those early days, where Pacific officials had the right institutional settings in place, Chinese contractors were able to deliver high-quality projects with long-lasting benefits, such as the dormitories at the University of Goroka. What matters is not the source of development finance, but the capacity of the host nation to use or misuse it.

In the past, Chinese diplomats were notorious for not showing up to donor coordination meetings, or showing up late, or spending the entire meeting taking calls. Under Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, China is making an effort to improve the quality of the staff it posts in the Pacific. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Commerce are appointing personnel who can engage with other development partners.

Lack of personnel will continue to hamper China’s efforts, but it is now more interested in working with other nations on development issues. And not all Chinese aid contractors are bent on a race to the bottom. Chinese companies with long-term commitments to the Pacific — such as COVEC PNG and the Guangdong Foreign Construction Group — have adapted to host-country concerns, localised their workforces, and learned how to work with multilateral and bilateral donors, including Australia.

Aid in the Pacific is one area where Australia can look to cooperate and coordinate with China. Roads in the Pacific rarely lead to nowhere; they help Pacific islanders get access to healthcare, education and markets for their goods. It would be unfortunate if the minister’s outdated view of China and the Pacific got in the way of our building them together. ●