Who will win the election on 2 July? With the first polls registering 50–50, the contest is competitive. The Coalition and Labor both have reasons to be optimistic – seven on each side, by my reckoning.

Seven reasons for the Coalition to be cheerful

1. Labor’s core election theme

The opposition’s election strategy so far – “fairness,” soaking the rich and promising to protect health and education – seems puzzlingly unsophisticated. Playing to its traditional weakness on the economy, this is the kind of unsubtle message Labor discarded decades ago.

If all elections were all about who will spend the most on health and education, there would be no Liberal prime ministers. But with swinging voters tending to prioritise economic security, promising to fork out more has always been a double-edged sword. It’s as if Labor reckons that deep inside every Australian’s breast beats the heart of an ALP true believer.

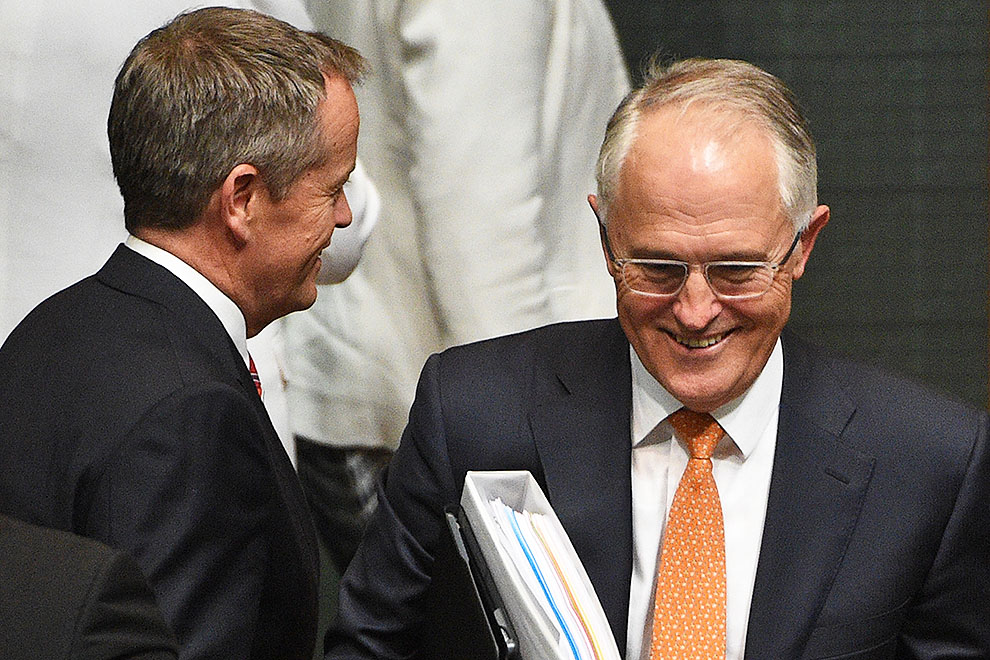

2. Bill Shorten

Commentators all but unanimously agree that the Labor leader has grown in stature and eloquence and is now “cutting through.” But that’s just the view through recent polling results: in reality, Shorten remains just as hemmed in, inarticulate and overly scripted as he was last year. He oozes insincerity, and his involvement in past Labor’s leadership shenanigans doubles down the dodginess.

3. Fears of union influence

Australians aren’t as antagonistic towards unions as Coalition party members are, but they do have mixed feelings. It tends to be forgotten that when Australians voted for Bob Hawke as prime minister in 1983 it was despite misgivings about potential union influence, and Shorten enjoys nothing like the trust and affection Hawke had.

Kevin Rudd in opposition took care to keep his distance from the labour wing, while Shorten, with his background, attempts to make virtue of necessity. His shadow workplace minister, Brendan O’Connor, plays to a limited audience.

Union influence is always an obstacle to a Labor win from opposition. And union membership keeps shrinking.

4. Queensland’s Palaszczuk government

If the opposition is to get over the line on 2 July, the result will need to include a very big swing in Queensland. Unfortunately for them, Labor is in government there. That’s a problem not because the Palaszczuk government is particularly on the nose; it isn’t (although neither is it soaring to Beattie-esque heights). It’s the road almost travelled that’s the issue.

Imagine how much more fertile the Queensland soil would be for Shorten if the Liberal National Party had survived in January last year to become more and more reviled (albeit minus Campbell Newman, unsalvageable in Ashgrove).

5. The Greens

Whether or not the Greens snatch any more lower-house seats on polling day, they will chip at Labor between now and then, tempting them to the left.

The Liberals seem set to preference the Greens in most seats that matter (via recommendations on how-to-vote cards), which would make quite a difference – in fact, about 10 per cent of the two-party-preferred vote. This would be nothing new; it’s how Adam Bandt won the formerly safe Labor seat of Melbourne six years ago, with diabolical political consequences for the Gillard government.

For a decade and a half, the Coalition has been warning of the dangers of a Labor–Greens alliance, and since 2010 the message has grown in potency. Any public contemplation of a minority Labor government, with the Greens throwing their weight around, assists both the minor party and the Coalition.

6. Labor’s big policy target

Labor is taking a big, fat housing affordability package to the election. So far it has been reasonably well received, but the government is warning that the policy will “smash” house prices.

When opposition leader John Hewson unveiled his GST in 1991 it was popular at first, too. Labor’s policy might be just what is needed, but taking it to an election was unwise. Watch as the scare campaign starts to bite.

7. Labor’s debt and deficit record in government

This is the opposition’s core weakness; they find it so troubling they simply ignore it. It wasn’t Labor’s fault that the Howard government’s surpluses turned to deficits in its hands, but most voters are convinced it was.

Labor may or may not have spent too much money in government from 2008 to 2013, but the amounts involved were dwarfed by the collapsing revenue and increased outlays produced by the global financial crisis. It was awfully unlucky with the economy, and then played the politics appallingly.

Despite the current government’s quite evident difficulties in this area as well, debt and deficits remain, at a visceral level among voters, a formidable barrier to Labor’s taking government. Yet the party seems to believe that if it just keeps turning the conversation to health and education then voters will be distracted from what they most prioritise.

This week, shadow treasurer Chris Bowen gave an impressive National Press Club performance, but fine words and appealing policies count for nought if electors suspect that Labor will just rip it all up and embark on a spending spree. Forget boats and climate change; perceptions of debt and deficits remain the biggest hurdle for a Labor victory.

Seven reasons for Labor to be cheerful

1. The economy

The Howard government lost office a little under twelve months before the bottom fell out of the world economy, which was splendid timing for its legacy. In opposition, Tony Abbott promised a return to those golden years; Joe Hockey even promised a return to surplus in the first year of government. That helped them get elected, but it wasn’t sustainable.

The international economy buried the Labor government; now the Coalition is struggling as well. The pre-2008 climate remains a distant memory, with wallets remaining closed and confidence low. Government debt continues piling up.

2. Malcolm the misfit

Upon entering parliament in 2004, Malcolm Turnbull was determined to be a different type of politician. For years he consciously avoided the mindless adherence to the party songsheet that characterises colleagues on all sides of parliament. The exception was his first stint as leader in 2008–09, when he had to get down and dirty. This time around, after initially announcing his intention to treat the voters as adults, he has been mugged by political reality.

He’s now just another politician, and he never looks comfortable in the role. Appealing to fears, telling whoppers about opponents, this isn’t why he coveted the top job; he yearns to be a better man.

The Coalition is much more likely to win the election under his leadership than it would be if still led by the man he replaced, but Turnbull is not as effective an attack dog as Abbott was.

Meanwhile, many on the right of the Liberal Party, spoilt by two decades of mostly conservative supremacy, remain embittered by the events of last September, and have been emboldened by the government’s recent poll slump. Abbott himself is an unpredictable variable. The “disunity is death” meme can be over-hyped, but Shorten’s warning that after the election the Liberals will start squabbling again is tactically sound.

3. The treasury portfolio

Treasurer Scott Morrison. The emperor is utterly starkers. Good taste prevents further elaboration.

His opposite number, Chris Bowen, by contrast, is likely to emerge as Labor’s campaign star (and, if it loses, favourite as the next Labor leader). He has largely shed that “Have I got a deal for you!” persona, is articulate, and presents warmth and believability – everything his predecessor Wayne Swan was not. And the economy is always an important battleground.

4. Bill Shorten (II)

Shorten, for all the faults outlined above, remains a basically electable commodity. He is not innately scary. Opposition leaders don’t have to be charismatic swashbucklers; they need to be an acceptable, safe alternative if voters are looking for change.

Boring is fine, and Bill is certainly that. He’s a Howard, not a Mark Latham.

5. Queensland’s Palaszczuk government (II)

Last year’s Queensland election result (and to a lesser extent Victoria’s) shows that, in the current climate, a conservative government can be demolished after one term, regardless of its majority.

6. The economy (II)

Politics is much harder in these days since the global financial crisis. Around the world, electoral contests have thrown up strange results.

It’s possible that Labor strategists actually know, for once, what they’re doing, and in their grumpiness swinging voters are prepared to throw economic caution to the wind.

7. Malcolm’s high approval ratings

Recent polling has the parties neck and neck, but with Turnbull comfortably ahead as preferred prime minister and enjoying higher approval ratings than Shorten. Contrary to stubbornly received wisdom, numbers like this at the start of a campaign have historically foreshadowed an improvement in voting intentions for the party with the less popular leader.

High personal ratings, it seems, may artificially inflate voting intentions. For a given surveyed vote, it is better to have low personal numbers than high ones.

Every one of Bob Hawke’s three re-elections displayed this pattern: a popular prime minister yet a healthy government lead whittled away during the campaign.

John Hewson began the 1993 campaign comfortably ahead in voting intentions and was easily preferred to Paul Keating as prime minister; the rest is history. Howard rampaged over Kim Beazley’s figures at the beginning of the 2001 campaign, when the Coalition led by about 56–44, but on election day the vote was 51–49.

The same goes for Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard in 2007 and 2010: both enjoyed high approval ratings, and led the figures for preferred prime minister, but the polls narrowed throughout the campaign.

The party with the most popular leader usually (but not always) goes backwards during the election. And these poll numbers (to me) are the most powerful – and perhaps the only – reason to anticipate a Labor victory. •