I was in the middle of writing an article about the three great Australian Medeas — Judith Anderson in 1947, Zoe Caldwell in 1982 and now, in 2020, Rose Byrne at the Brooklyn Academy of Music — when I learned of Caldwell’s death. A “sexy dame” with red hair and freckles who “talk[ed] a blue streak,” her career intersected with that of her Australian predecessor on the American stage, Judith Anderson, in a series of intriguing adventures and misadventures.

Born in Melbourne in 1933, Caldwell, like the young Anderson, came to theatre through elocution classes and competitions. Her first professional engagement was in Peter Pan at the age of nine. By the time she was in secondary school, she was doing radio work after school, taming her throaty voice into the subtle instrument that audiences loved.

In 1953 John Sumner invited her to join the newly formed Union Theatre Repertory Company, where she learned her craft. She was the company’s star in 1955 when she was chosen to appear with Anderson, the visiting superstar, in the national tour of Medea that inaugurated the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust. Playing the small part of the second woman of Corinth, she observed Anderson with an eagle eye:

She arrived like a diva come to sing her role… We practically curtsied. Then, without taking off her high-heeled ankle-strap snakeskin shoes (she had lovely legs), or changing out of her honey-coloured cashmere sweater and skirt (no bra — in the 1950s! — she had good breasts), she began to rehearse. Immediately we knew that we were not God’s chosen.

Over the length of a three-month tour (opening in the very inadequate Albert Hall in a Canberra of about 30,000 souls), Caldwell came to respect Anderson, but not to love her. “That,” she wrote in 2001, “had to come later.”

Considered Australia’s finest young actress, Caldwell went to England when she was twenty-four on a scholarship to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon. In 1963 she joined the Minneapolis repertory company of Tyrone Guthrie, with whom she had worked in Stratford. Critic Claudia Cassidy of the Chicago Tribune, who had always been a great supporter of Judith Anderson, was equally admiring of this young Australian, who had, like her predecessor, “voice, manner and style.” Three years later, at the age of thirty-three, she was discovered by Broadway, where she immediately won a Tony award for her role in Tennessee Williams’s Slapstick Tragedy. Within another two years she had won another Tony for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. The same year, 1968, she married her producer, Robert Whitehead.

Whitehead had had his own history with Judith Anderson. In 1947 he and his partner Oliver Rea had made their sensational debut as producers of Anderson’s landmark performance in Robinson Jeffers’s Medea. It had been a baptism of fire, with Anderson determined that the play she had plotted and planned for twenty years would be presented exactly as she had visualised. She and the two young producers fell out irretrievably, and her triumphant tour was produced and directed by her old friend, the much more experienced Guthrie McClintic.

Since this early contretemps Robert Whitehead had become one of America’s most successful and influential producers, often in collaboration with wealthy businessman Roger Stevens. Over the next few years Caldwell combined motherhood with appearances in London’s West End as Lady Hamilton in Bequest to the Nation, as Colette off-Broadway, as Eve in Arthur Miller’s The Creation of the World and Other Business, as Alice in Strindberg’s Dance Of Death, and as Mary Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey into Night. She also started a career as director in 1978 with An Almost Perfect Person, starring Coleen Dewhurst.

In 1979 the eighty-two-year-old Judith Anderson (by then Dame Judith) was lamenting that she was “no longer in demand.” When she saw that Robert Whitehead was in California (where she had lived for many years), she called him, forgetting their long-ago feud, to suggest he revive Medea. She herself would play the nurse, she told him, and she had just the person to play Medea: an actress she had seen playing Sarah Bernhardt on television two years earlier — Zoe Caldwell.

Anderson had not recognised the young woman who had played one of the chorus in Medea in 1955. Nor had she known that this three-time Tony winner was married to Whitehead. In fact, in suggesting this revival of her great play, she found herself courting theatrical royalty. Whitehead and Caldwell leapt at the idea of a Medea revival, though both were apprehensive, for different reasons, about working with Anderson.

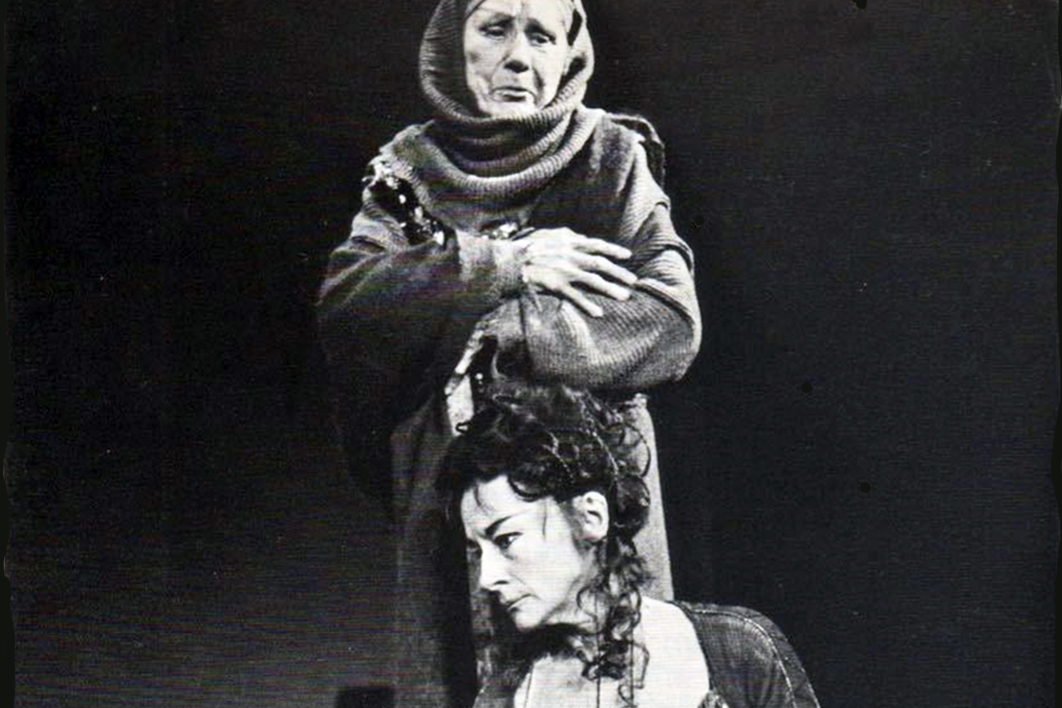

In the event, it was a brilliant success. Whitehead had called on his old friend and partner, Roger Stevens, for the venue, the Eisenhower Theater at the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts in Washington, DC, of which Stevens was the chairman of the board and “Master Money-Raiser.” The new Medea opened early in February 1982 at the Clarence Brown Theatre at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, for a two-week preview. After the first performance, to mark the passing on of the role, Anderson presented Caldwell with the Mucha poster of Bernhardt as Medea that she herself had received in 1947. On opening night at the Kennedy Center, David Richards of the Washington Post found Caldwell “mesmerising.” Against the background of Ben Edwards’s classical set, with its massive pillared doorway “rising into the chill of a starry night,” Caldwell accentuated Medea’s foreignness — her exoticism and her sexuality.

The Post’s music critic Joseph McLellan was old enough to remember Anderson in the role, and felt that Anderson’s “relatively understated” performance had had more impact than Caldwell’s operatic, Tosca-like approach. But Caldwell’s interpretation of the role fitted well with the eighties’ fascination with “difference.” Richard L. Coe, the Post’s veteran drama critic, hailed Caldwell’s “awesome daring and ingenuity” in a performance he would remember, he wrote, for a lifetime. “She gives us a blazingly barbaric Medea,” he wrote, “someone far beyond the horizon of the Greeks, fully capable of the magic with which Jason could obtain the Golden Fleece. She is not a Greek and, ill at ease in their terrain, expresses natural force against the serene civility of her husband’s people.” “The concept is wholly unlike Anderson’s,” he continued:

Her Medea had tried to assimilate a civilisation she respected. She was an outsider who had made it into the inside. Caldwell’s Medea remains the outsider, battles for her individuality and scorns what to her are the new mores. Africa looking at the rest of the world? The Uzbeks scorning directions from Moscow?

Choosing this image, the actress goes at it with no holds barred. She writhes, undulates, caresses her thighs. Her voice never hits the same tone twice in succession. Blazing from within, her eyes see only a vengeance invisible to others. Her passion is both exotic and believable, and mainly because of her, so, too, is the production.

Commentators were intrigued by “the strange sequence of chance encounters, bizarre parallels, hard words and shared memories” that led to this Medea — the fact that Robert Whitehead had produced the original 1947 performance by Anderson; that the young Zoe Caldwell had played in the chorus when Anderson had taken the play to Australia in 1955; that Anderson had seen Caldwell’s television performance as Bernhardt and had told Whitehead she must play Medea, not knowing that the two were married. Most of all they loved the fact that Anderson was now playing the nurse to Caldwell’s Medea. As Anderson put it, “If anything ever came full circle, this is it.”

Critics praised the decision to cast Anderson as the nurse and were full of admiration for her performance. “Time has not eroded the gravity of Anderson’s voice nor the dignity of her presence,” James Lardner wrote in the Washington Post. “She gives a touching performance as the befuddled witness to Medea’s horrible acts.” But, he added, “above and beyond the particular distinctions of this revival” there is the sense of a torch being passed along. Unlike its European counterparts, he pointed out, the American theatre is more cavalier about such matters of tradition.

When the play opened on Broadway on 2 May, Frank Rich at the New York Times was enthralled by the “special flame” that Caldwell brought to the character of Medea. “Euripides demands an intense psychological realism from actors,” he wrote, “and that is what Miss Caldwell has bestowed on her marathon role.”

This actress makes us believe in the warped logic by which Medea murders her two sons to wreak vengeance on Jason, the ambitious husband who has betrayed her for a Greek princess. And because she does, we are, by evening’s end, brought right into the thunderclap of Euripides’s tragedy.

Equal heroine of the hour was Dame Judith, greeted affectionately from the welcome-back ovation at the theatre to the “hands reaching out to make contact with the tiny, eighty-one-year-old actress” at the opening night party at Sardi’s, which “hummed with reminiscence… as ageing theatre-goers boasted, with a certain rueful bravado, of having seen the 1947 production starring Judith Anderson.” Glenne Currie of United Press International stated simply, “Dame Judith, now playing the nurse, will break your heart.” Jack Kroll, in Newsweek, noted that Anderson “plays the nurse with an eloquent simplicity that’s beautiful to behold.” Edwin Wilson, reviewing what his headline called “A Strong Play about the Agonies of Apartheid” in the Wall Street Journal, praised her for “the poise and power of an actress half her age.” Clive Barnes in the New York Post admired her “magnificently gnarled dignity.” Variety, more cynically, called it “an impressive performance from a venerable legit star, and incidentally a shrewd bit of casting.”

Both Zoe Caldwell and Judith Anderson were nominated for Tonys for their performances. Caldwell, pitted against Katharine Hepburn in The West Side Waltz, Geraldine Page in Agnes of God and Amanda Plummer in A Taste of Honey, was the winner of the Best Actress award; Anderson, competing with Mia Dillon and Mary Beth Hurt in Crimes of the Heart and Amanda Plummer in Agnes of God, lost to up-and-coming young Plummer in the Best Featured Actress category. She had, after all, won a Tony for her original performance in Medea in 1947.

The new Medea reached a huge audience when a ninety-minute television version was shown on PBS in April 1983 as part of Kennedy Center Tonight. Filmed in Canada and skilfully directed by the BBC’s Mark Cullingham, it was hailed as “a lesson in classical acting which will remain as unforgettable for viewers as the tragic theme itself.” “Dame Judith counterpoints the shrill harshness of Medea with a calm melancholy,” Arthur Unger wrote in the Christian Science Monitor. “To Miss ‘Medea’ Would Be Tragedy,” the Chicago Tribune headlined. In a masterly discussion of the differences between the stage and the television productions, John Corry of the New York Times called the latter “a triumph of nuance.” “The camera changes the focus,” he wrote. “Other things swim into view.”

Judith Anderson’s nurse, for one, is more imposing on television, more full of presence. Miss Anderson looks, she listens, she scarcely seems to be acting at all. When the nurse tells Medea that she has seen Creon and his daughter burning alive, the flesh falling from their bones, Miss Anderson speaks quietly, but it is certain that even as she speaks she sees the flames. The camera, forcing us to look squarely at Miss Anderson, Miss Caldwell huddled against her, narrows our vision. We see with a different mind’s eye.

The following year Zoe Caldwell opened the Victorian Arts Centre in the Melbourne Theatre Company’s production of Medea with an Australian cast, featuring Patricia Kennedy as the nurse and John Gregg as Jason. Reviewers agreed that this was “ancient Greek theatre at its best,” “an unforgettable experience” and “an astonishingly original creation.”

Whitehead and Caldwell had initially been terrified at the thought of doing the play with its former star in the production. But it turned out to be a triumph, artistically and personally. “I think it’s terribly important for actors to have a chance to work with other actors who have become part of their traditions,” Caldwell told one reporter. “It’s like life, death and rebirth.” Whitehead was grateful that he and Anderson had achieved a friendship that made him aware of all he had lost during the thirty years they had been estranged. In memory of the production and their new friendship, Whitehead and Caldwell gave Anderson a dachshund she named Bozo in their honour, one of the long line of dachshunds who had been her companions for many years. When she became ill in 1991 and had to receive visitors in her elegant bedroom looking out on the magnificent Santa Ynez mountains, Bozo reclined at her feet — one eye always on her, a friend remembered. (She died five months later, in February 1992.)

Caldwell’s career as actor and director continued its upward trajectory after Medea, with Master Class, her legendary depiction of Maria Callas in 1995, winning her a fourth Tony. She made a cameo performance as the Countess in Woody Allen’s Purple Rose of Cairo in 1985. From the early 2000s, as the Parkinson’s disease that eventually took her life set in, she restricted herself mainly to voice roles on television and video games. When she died on 16 February, Michael Coveney in the Guardian described Medea as one of her greatest roles. •