The death of Barry Humphries in April this year brought forth abundant reminders of his remarkable and diverse talents and achievements. Actor, writer, poet, artist, bibliophile: Humphries was a gift to obituarists because he was rarely out of the limelight either as himself or acting out parts of himself in the many personae he created.

But while others were revelling in their favourite memories of Edna Everage, Les Patterson or Barry McKenzie, I took myself off in a different, quieter direction: to 36 Gallipoli Crescent, in fact, a street fictitiously located in the real Melbourne suburb of Glen Iris. This was the home of Sandy Stone, the most subtly drawn of all Humphries’s characters. I had no strife finding a “pozzie for the vehicle,” as Sandy often said of his own parking misadventures, because comparatively few people remember this boring old beggar (a polite euphemism for bugger in Sandy’s day).

Humphries, born in 1934, grew up in nearby Camberwell, where his father became a prosperous master builder. Eric Humphries built three houses for his family in Christowel Street, numbers 30, 38 and 36; the last was where they settled for good in 1937. Sandy and Beryl Stone’s imaginary house at 36 Gallipoli Crescent was built on these memories, although whether the style was mock Tudor, mock Elizabethan, neo-Georgian, Spanish mission or Californian bungalow Sandy doesn’t say. Eric Humphries could build them all. There was a driveway for the vehicle, a shady porch, and a tradesman’s hatch at the side. Sandy and Beryl called it “Kia Ora,” a Māori phrase for “hello.”

The Stones’ life together began just as the Depression was easing. On Sunday afternoons, while Kia Ora was being built, they would come and sit on the joists with a thermos and a pile of Australian Home Beautifuls. It’s never clear what sort of job Sandy had, but the couple were comfortably off and could afford the sorts of conveniences much prized by Humphries’s desperately aspirational parents. They had an electric refrigerator instead of an ice box, an electric stove and oven instead of an Early Kooka, and an indoor toilet instead of an outdoor dunny covered in morning glory.

In Sandy and Beryl’s garden there were “rhodies” and “hyderanges” (rhododendrons and hydrangeas), a silver birch and maybe a “jaca” (jacaranda), but probably no roses (Humphries’s mother thought them “a bit old-fashioned”) and certainly no shaggy eucalypts. Eucalypts, as well as paling fences, chicken coops and any structure with a corrugated iron roof, were considered emblems of the working-class existence Humphries’s parents had managed to escape. After their wedding, Eric and Louisa Humphries had moved from the less respectable suburb of Thornbury, but, as it turned out, only a bluestone lane separated the houses in Christowel Street from a remnant pocket of poverty in old Camberwell.

“We stared at each other sometimes, the poor and I,” Humphries later remembered, he on a ladder propped against the back fence, the poor children, with their bloodied knees and runny noses, staring back from their derelict backyards.

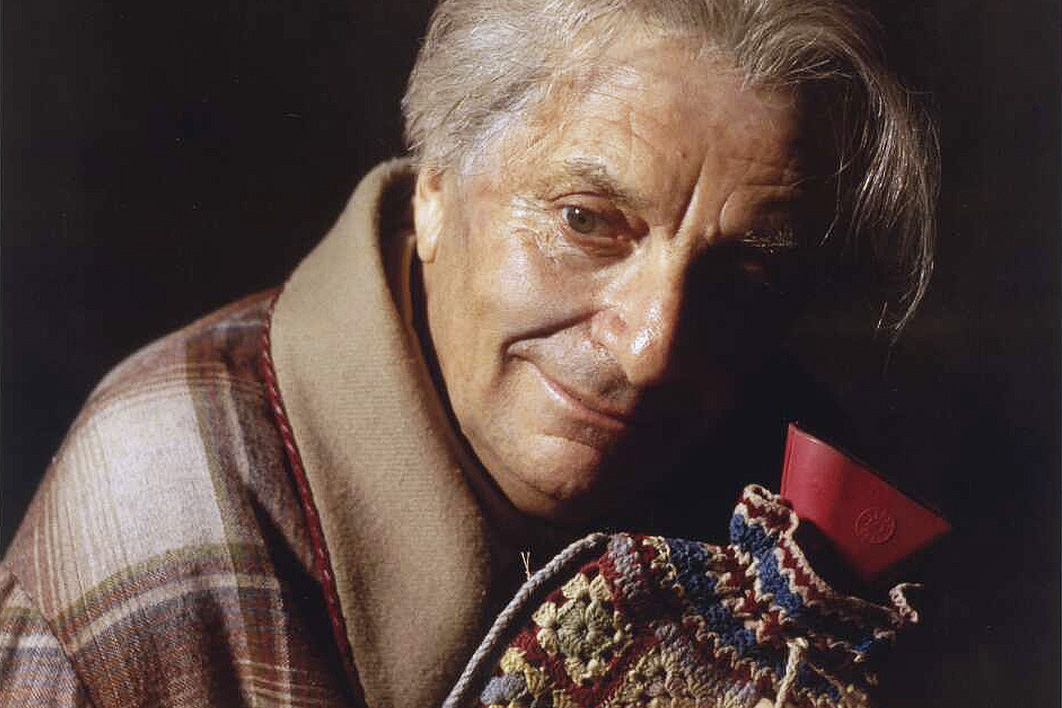

The Sandy Stone monologues were written either for sound recordings or as the “adagio act” in Humphries’s live touring shows. He published the collected scripts in 1990 under the title The Life and Death of Sandy Stone, edited by his friend Collin O’Brien. A television series of the same name was broadcast that year by the ABC, recorded in front of a studio audience whom Sandy addresses from his patterned velvet armchair. He is always styled as a middle-aged-to-elderly man, in a dressing gown and slippers, cradling a hot water bottle.

Often Sandy pauses an anecdote to note with deep approval that someone was a “Returned Man,” once a common term for someone who had fought abroad in one or both of the world wars. There was his friend Pat Hennessy, who’d recently had occasion to bury his wife and who was so lost without her that in three years he’d not cleaned the S-bend in his toilet. He was a returned man. So was their local postie, and so was the specialist who broke the news to Sandy and Beryl that they could never have children. As for the vestryman up at Holy Trinity church whose son was a hippie: although not actually a returned man, he was “one of the nicest people you could ever wish to meet.”

My parents and I never missed an episode of the ABC series and my father delighted to imitate the exact note of serene reverence in Sandy’s voice when referring to a “returned man.” Dad’s father George really had been a returned man, a quiet sort of chappie, Sandy would have said, and to look at George nobody would have thought he’d been a prankster and a scallywag before enlistment. But after service on Gallipoli and Pozières he returned silent and deeply introverted, happy to accept an office job and a peaceful life in the suburbs. But he did retain the impish sense of humour that has become a family trait, hence my father’s rich appreciation of Sandy Stone.

With Barry Humphries’s death I thought back to those evenings in front of the telly with my parents and became curious about Sandy’s actual returned status. I found it surprisingly ambiguous. Sandy is a regular at his local RSL, and when he needs to have a surgical operation — a “little op” — he is entitled to have it done at “the Repat,” which as his Melbourne audiences would have known was the Repatriation General Hospital in Heidelberg. (The general term “repatriation” has fallen into disuse but was once a uniquely Australian descriptor for the return of Australian men and women after war service, and their further support through pensions and benefits.)

Sandy has obviously served in some capacity, but what? He first appeared in 1958 in a sound recording, “Days of the Week,” written as the B-side for a 45rpm record. (Mrs Everage took the A-side.) Also in 1958 Humphries published a short story entitled “Sandy Stone’s Big Week” in the Canberra student magazine Prometheus. Nothing happens in Sandy’s “big week.” A pot-bellied Sandy is discovered in his garden in the early evening watering his shrubs. As the light dims, all that is visible of him is his white shirt “and the white arc of water from his garden hose.” Called inside by Beryl, he goes in, switches on the wireless, seats himself in the patterned velvet armchair, rolls a cigarette (later he is a non-smoker) and thinks about the events of the coming week. The highlight will be an RSL meeting on the Friday night at Gallipoli Hall. That’s it.

Nothing much ever does happen to this emasculated Anzac. He makes a trip back to Gallipoli in 1968 with a group of cobbers and a Turkish guide (who spoke “perfect Australian”) and writes a painfully dull letter from the “Istanbul Hilton” to Beryl about the few hours they’d spent stumbling around the peninsula getting souvenir snaps. Perhaps this monologue was prompted by historian Ken Inglis’s reports for the Canberra Times of the 1965 RSL pilgrimage to Gallipoli, but Humphries ultimately rejected the idea of making Sandy a first world war man, and this piece, “Anzac Sandy,” was never performed.

Instead, the second world war became Sandy’s war, although, as Humphries himself admitted, Sandy’s military status was still nebulous. The development of the character coincided with growing scepticism among some Australians, bordering on hostility, towards all things Anzac in the 1960s, but Humphries avoided using Sandy as a vehicle for the kind of biting critique that Alan Seymour explored in his play The One Day of the Year, first performed in 1958. Nor was Sandy a violent, war-damaged tyrant like the father in George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964). And again, Humphries was uninterested in the public debate over the system of repatriation that was satirised in John Whiting’s polemical novel Be in It, Mate! (1969).

Sandy was never about any of that. The point of Sandy was to be boring. His creator’s declared aim was to see how far he could bore audiences before they rose up in revolt. Acknowledging the influence of Samuel Beckett and the avant-garde art movement known as Dadaism, with its explorations of nonsense and irrationality, Humphries wanted not to please his audiences but to provoke and shock. Gradually he alighted on the idea of boredom as the way to do it and, turning inwards, found all the material he needed within the suburban wasteland, as he saw it, of his youth.

Hence Sandy’s maddening, circumlocutory monologues punctuated by pointless pauses, digressions and repetitions. His attention will get snagged on a point of inconsequential detail and audiences watch, transfixed, as he struggles to free himself. This, for instance, from “Shades of Sandy” (1981):

Little Gwennie’s husband, Jack, went to his Reward about two years ago. Yes, it would be two years since Jack went to his Reward. It would be a good two years. It would be all of a good two years.

Also in that monologue is Sandy’s immortal critique of the domestic pop-up toaster, specifically the Morphy Richards model that threw Beryl across the room one day when she tried to dig a crumpet out with a fork. No matter the brand of toaster, the crumpet is never taken into account. “You slip one in and half an hour later, if you are lucky, it glides to the surface, as white as a lily.” But sometimes the opposite happens:

Flames leap out of the toaster. You’ve got to bash it underneath with a broomstick, and then you’re on the kitchen floor trying to find it, and over the sink, scraping off the black fur till there’s nothing left but a couple of crumpet holes. A black crumpet hole is no use to man nor beast.

There is a little knob on the side of the toaster, Sandy continues, to indicate light to dark. Easy to miss. Beryl missed it for years and then, when she found it, she couldn’t leave it alone. But the interesting thing, he concludes, is that “it’s not connected to anything” (Sandy’s emphasis). “It’s got a mind of its own.”

Ruminating in 1990 on the origins of Sandy, Humphries recalled how, after having dropped out of university, he succumbed to parental pressure and took a “real” job in the city with the EMI record label. On his morning commute, always running late, he often met his neighbour Mr Whittle, a childless man of his parents’ age who would invariably greet young Barry with “a polite and old-fashioned little squeeze” of his grey trilby hat. For Humphries, this man came to epitomise not just his parents’ generation, but “Respectability Itself”: punctuality, industry, courtesy, thrift, temperance, niceness. “I despised him.”

In 1956, desperate to escape, Humphries got married and snatched an acting job in Sydney. He was unhappy there too, especially in the depressing old boarding house near Centennial Park where he and his wife Brenda were staying. Breakfast was had in a shared kitchen with other tenants, mostly aged and itinerant men, all lonely. Walking along Bondi Beach one blustery winter’s afternoon, Humphries encountered a wiry old fellow of about sixty-five with thin sandy hair, finely capillaried cheeks, a two-tone cardigan and “freckled, marsupial paws.” When Humphries asked the time, he was told: “Approximately in the vicinity of half past five.”

In that moment, he had the last pieces in place to create Sandy Stone, including the sibilant “S’s” caused by ill-fitting dentures, and the thin, dry voice Humphries recognised as “the antithesis of the rugged Australian stereotype.”

What unified these men in Humphries’s mind, I think, was not their ex-digger status but his perception of them as lonely, ageing men. Confused and anxious about his future, perhaps his greatest fear was that he would end up like them. True, Mr Whittle did wear a returned serviceman’s badge on his lapel, but Humphries was careful not to overplay that. Sandy could not be a war bore because he would have had to bore audiences on subjects about which Humphries knew little.

Instead, Humphries turned to a subject on which he was an expert, life in the Australian suburbs. To express his rage and frustration at the tedium imposed upon him in his youth, he needed a technique that would be, he said, “monumentally, grindingly prosaic.”

The most interesting occurrence in Sandy’s life is his death, which occurs in his sleep while Beryl is absent on the Women’s Weekly World Discovery Tour that she had been hankering to do for years. Death frees him to return as a ghost.

He enjoys watching his own funeral and the wake afterwards back at Kia Ora. He watches as Beryl puts the house up for sale and disposes of his effects, assisted by their neighbour Clarrie Lockwood from 43 Gallipoli Crescent. Clarrie heaves Sandy’s armchair into his Vanguard ute along with various other bygones of Sandy and Beryl’s life together, and takes them to the Holy Trinity opportunity shop. It is obvious to everyone except Sandy that Beryl is more gleeful than grief-stricken, and after the house sells she moves to Queensland, where she and Clarrie later marry.

Kia Ora is bought by Mr and Mrs Cosmopolis, “a delightful multicultural ethnic minority Greek couple,” who are expecting a baby. Mrs Cosmopolis notices Sandy’s armchair in the op shop and buys it, and so, in Sandy’s final monologue, “Sandy Comes Home” (1985), we find him back at 36 Gallipoli Crescent, still in his old armchair, watching his house being renovated.

This monologue cracks open the racism that Sandy has been putting down in layers since the 1930s, when fruit and vegetables were delivered to Kia Ora through the tradesman’s hatch by the “yellow hand” of the “little smiling Chinaman,” Charlie O’Hoy. Sandy could bestow a tolerant glow over Charlie, and the Greek couple who operated the local fish and chip shop, and even the Angelo brothers, Italians who as terrazzo specialists did most of the porches in the street.

But when in 1938 an “Israelite” couple named Eckstein moved into the first block of flats in Glen Iris, they were the “thin end of the wedge” as far as Sandy was concerned. They opened the floodgates and then it was “Come One, Come All.”

The Stubbings’ beautiful home at number 52, for instance, was bought recently and remodelled by a Vietnamese couple called Ng. That’s their name, Sandy tells us, incredulous, and “you could smell their cooking on the bowling green.” Number 37, the home of Vi and Alan Chapman, was bought by Bruno Agostino and his family of eleven.

Once they moved in, that once-lovely home was swarming with dagos night and day. Talk about build. They built on the back, they built on the front, they built on the left, they built on the right… they built a balustrade right across the front of the home, with fountains and statues and lions everywhere. It was like a cement safari.

The Agostinos dug up all of Vi’s “magnificent” garden, including the pin oak Vi bought as a seedling years before from the Methodist Church fete. It resisted the bulldozer for the best part of a day, until the “Eye-ties” got a block and tackle to it and finally it came down “with a groan you could hear up and down the crescent.”

Only as they chopped it up did the Agostinos discover a bit of rotten wood nailed on to one of the branches, which was all that was left of the treehouse little Neil Chapman had played in before the war.

Of course, little Neil was beheaded in Borneo. Some Jap with a sword said “Neil!” [kneel] and he did, and that was that. It’s terrible to think that your destiny can be in your own name.

Sandy gives no pause here, but rambles on remorselessly as he always does, leaving audiences, I’m sure, wide-eyed and silent. The monologue ends with Mrs Cosmopolis bustling in to clear away the last of the things that Beryl hadn’t bothered with, including Beryl and Sandy’s wedding photo and a lock of his mother’s hair, which he’d been keeping in a cigarette tin.

“Sandy Comes Home” appears to be the last Sandy monologue Humphries wrote, and was the longest. By then audiences had been allowed to develop a certain affectionate sympathy for Sandy, which made his racism even more shocking. Humphries always enjoyed the deep hush that greeted Sandy’s anti-Semitism. “Perhaps,” he mused in 1990, “we had not until then fully apprehended that we, who had invented Niceness, could also be very nicely anti-Semitic. It was a salutary discovery.”

Sandy’s ex-service status was just a device to tie him to the past and associate him with the most conservative element in Australia at the time, the RSL. The young Barry Humphries had spotted a much older man — his neighbour Mr Whittle — and despised him for his “respectability.” For comedic purposes he was uninterested in the idea that people of Mr Whittle’s generation had lived through and suffered much. But after two economic depressions (1890s and 1930s), two world wars and a cold war, small wonder that they took refuge in suburban routine and hard-won material comforts.

Humphries himself became rusted on to his long-held desire to shock, and over many years must have developed an ability to avert his gaze from the real pain he could inflict. His transphobic comments in 2016 seem to bear this out.

A word about Mr Whittle. Kenneth Roy Whittle was born in 1897, trained as a surveyor and became a public servant. He and his wife Alice moved into 42 Christowel Street, Camberwell in the early 1930s. He was not an ex-serviceman; there is no evidence he enlisted or attempted to enlist in either world war. Nor were the Whittles childless. Their only child, June Elizabeth, died in 1933, aged two, the year before Barry was born. Had she lived they might have been playmates. •