With forty participating countries and twenty-seven grand final performances, Eurovision 2015 was the sixtieth episode in the longest-running and biggest music competition in television history. Audiences topped 200 million, and some 16,000 people attended the live concert at the Wiener Stadthalle in Austria.

It’s quite a contrast with the inaugural contest, held at the Teatro Kursaal in Lugano, which featured performers from just seven countries. Thirty-year-old Lys Assia from Switzerland took out the prize that time, sharing the small curtained stage with a twenty-three-piece orchestra and grand piano. She was charming, the song was charming, and her dark frock, ornamented with a discreet diamond brooch at the neck, would have distracted no one from the musical qualities of her delivery.

That was 1956, the year television first came to Australia and a certain housewife from Moonee Ponds helped introduce the new medium to its suburban audience. Mrs Norm Everage could surely never have imagined how far she was to go in the decades ahead, yet there is a curious parallel between the way she and Eurovision evolved from their demure origins into ever more spectacular manifestations of glamour.

And so, when Australia was invited to participate in Eurovision 2015, Dame Edna’s supporters petitioned for her to be our representative and, excruciating as the consequences would surely have been, I can’t help feeling disappointed that this planetary conjunction didn’t take place. Which of the radiant bodies would have gone into eclipse?

Guy Sebastian, our eventual representative, was an obvious choice in another way: he’s a stylish singer with real musicality and he has written a remarkably good song. But those involved in the selection made a category error. The first thing to remember about Eurovision is that it is no longer a song contest.

On Planet Eurovision, lighting designers are now the dominant species. They have conducted a war on gravity, creating a hyperspace environment in which floors dissolve into bottomless pools of darkness, oceans of extreme colour wash through from all directions, galaxies of stars spray out in continually changing formations and batteries of laser beams shoot into action with every crescendo in the sound.

“Contestants, the stage is yours!” declares Conchita in the opening ceremony, but it is patently not so. The stage itself is already performing like crazy before anything so insignificant as a human gets on the scene.

From the contestant’s point of view, the options are stark. One option is to compete with the environment by trying to harness its star power, a feat last year’s winner Conchita managed to repeat. Aside from the gimmick of the bearded face amidst the cloud of feminine hair, Conchita has pretty much everything it takes to make an impact. She’s the queen of the crescendo, with a consummate sense of gesture and physical command, and knows how to wear a glamour frock as if it has grown out of her like some glittering carapace. She became the dominant presence at this year’s show, sidelining the new crop of divas.

If last year was the year of the boy bands, this was the year of the divas. Those who fared best in the voting were Aminata from Latvia, a singer of some panache and virtuosity who was ranked sixth, and runner-up Polina Gargarina of Russia, who demonstrated her commitment to the overblown melodrama by weeping copiously through the applause. For my money, Greece’s Maria Elena Kyriakou was a better singer, but she only came nineteenth. Serbian Bojana Stamenov, ranked tenth, was testament to the maxim that if you are twice as big as the other girls you’d better be twice as good. She projected both ease and power in the vocal delivery, and a very nice sense of operatic parody in her stage persona.

Some of the more experienced singers opted for a second approach, ignoring the pyrotechnics and relying on their inherent strengths as performers. This proved a big mistake for France’s Lisa Angell, a class act in every respect, who demonstrated that the way to deliver a ballad was to understand it from the inside out. She came in with only four votes. Knez from Montenegro, a musician widely respected in the region, held to traditional lyrical qualities and rode the crescendos with ease.

Those who attempted to trade on personal style had mixed fortunes. British duo Alex Larke and Bianca Nicholas bombed out (twenty-fourth in the final) with a retro bebop number that just didn’t have any impact amid the blitzkrieg of swirling colour to which they were subjected in the choruses. Our own Guy Sebastian came in fifth with a better-judged presentation, keeping it light and never forcing the energy. The song was rhythmically intricate and inventive, laced with his trademark vocal quavers, and he really hit the mark. Loïc Nottet of Belgium (fourth) nailed a triple pirouette half way through his song, which gave a much-needed lift to the dreary beat and lop-bop lyrics.

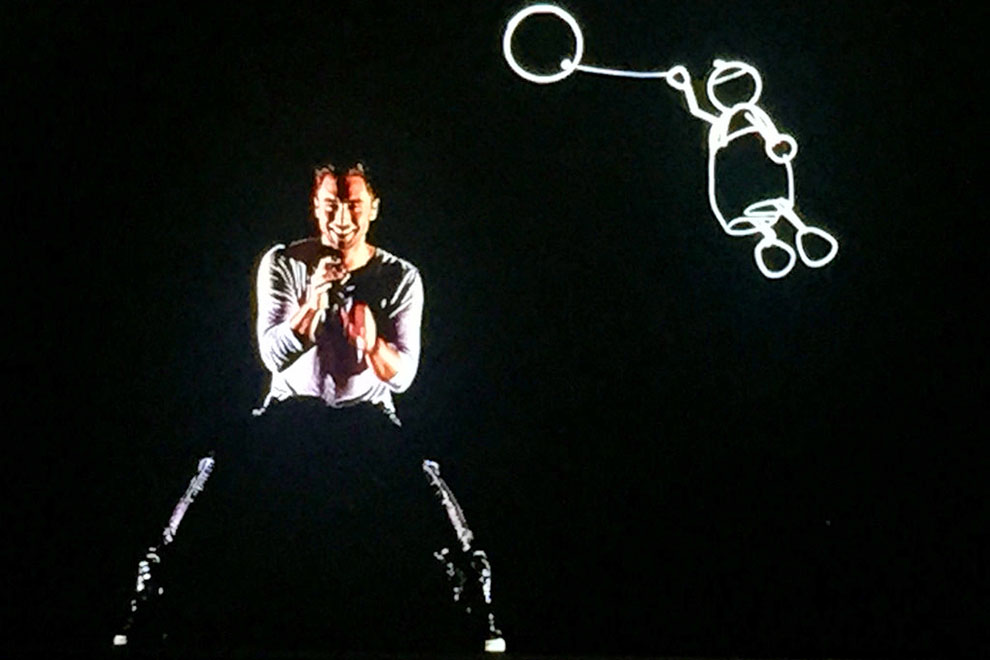

And the winner? Given that none of the divas had much chance in the presence of Conchita, maybe there was a certain logic to the choice of a guy in a grey t-shirt who has an utterly different approach to stage command. Måns Zelmerlöw from Sweden started off sitting on a bench in the darkness, singing quietly into a hand-held microphone. After a few lines, he clicked his fingers to produce a puff of brilliant white smoke, which then morphed into a cartoon figure. In the circumstances, it was a stroke of genius. At last the lighting was back where it belonged, in the service of the performer.

Australian viewers were fortunate to have Julia Zemiro and Sam Pang as commentators. Zemiro loves to play the party girl for the camera but is sharp as a tack in identifying the distinctive qualities of a performer and immensely knowledgeable about their background. Pang has a silly streak that works to deflate the overblown pretensions of the whole affair.

There has been some morning-after speculation about whether Australia has a future with Eurovision, but I’m left wondering about the future of Eurovision itself. Having extended its telecast reach to China this year, it may be preparing to take over the world, but just how can this television goliath continue to sustain itself? At some point it will surely implode, or just circle right out of our orbit. •