Based in a nondescript office in inner Sydney in 2016–17, a secret team set about saving the publisher’s newspapers

Fairfax’s blue team

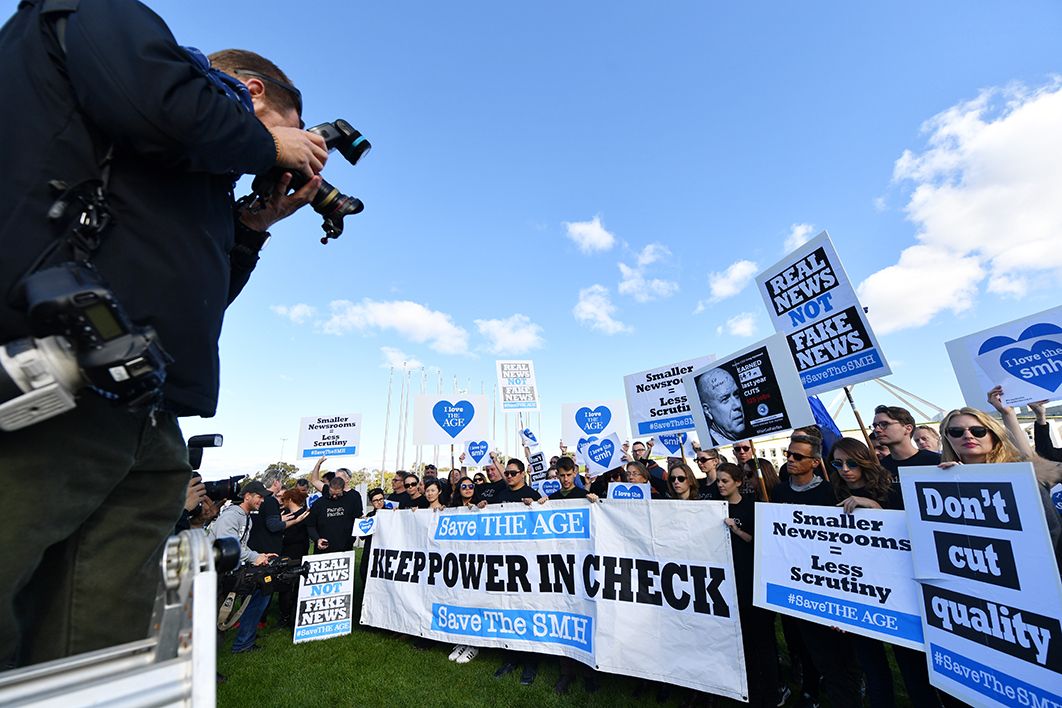

Never again? Journalists from the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age protesting against job cuts outside Parliament House in Canberra on 8 May 2017. Lukas Coch/AAP Image

Sydney office space offered some intriguing media echoes during the years of upheaval in the industry. In Pyrmont, Google took over what was once Fairfax Media’s Sydney headquarters. In Surry Hills, online youth publisher Junkee Media was run from the expensively decorated office space previously occupied by MySpace. And in Chippendale, Mumbrella’s office stood on the corner of Balfour Street and Queen Street, close to the spot where in 1960 the employees of the Packers and the Murdochs fought for control of Anglican Press printworks.

And then there was an office in Crown Street, Surry Hills, directly above trendy Bill’s cafe. Once it was home to MCM Entertainment, for a time one of the biggest players in Australian radio syndication and a promising innovator in video-streaming technology. And for five brief months it would house a team of nearly fifty people secretly working out a plan to save two of Australia’s most important newspapers.

Those who cared about newspapers were becoming resigned to the fact that Australia was about to lose the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age. The drumbeat that only the weekend editions would stay in print was getting louder. Yet there were no prominent examples of when a move by a newspaper to a digital product had been anything other than a last, failed throw of the dice. Beloved pets go to a farm, failing newspapers go digital-only. Tackily, bookmakers William Hill issued a press release in May 2016 headed “The Newspaper Death Sentence” offering odds on which Australian paper would close first. The Age was favourite at $2.60, while the Sydney Morning Herald wasn’t far behind on $3.20.

If journalism was to be saved, there were no playbooks to be found overseas. In the United States, many city newspapers had already closed. Two-paper towns had become one-paper towns, and one-paper towns were being left without a paper at all. In part that was newspaper economics, although it was also exacerbated by the fact that many US papers were owned by debt-laden companies. The only US papers that seemed to be healthy were the Washington Post, which was bought in 2013 by wealthy Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, News Corp’s Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times, which was cementing its position as the global newspaper of record in digital subscriptions.

In Britain, the national market had been retreating. In 1995 News Corp’s Today newspaper had been the first national daily to drop out of the market in a generation. The Independent had kicked off the trend of switching from broadsheet to compact in 2003, but was now on its last legs, with the final printed edition soon to follow, prior to an afterlife as a clickbaity website. Fairfax would have to figure out the problem for itself.

The 2012 cuts had won the company a little more time. The purchase of Antony Catalano’s real estate offering, the Weekly Review, was helping Domain take on the News Corp–aligned REA Group. And there were early signs that the investment in Stan, which had launched in 2015, was working.

Greg Hywood took an approach that had never been attempted before. He recruited Chris Janz to lead what he labelled “the blue business.” Allen Williams, managing director of the Australian Publishing Media division, was in charge of “the white business.” The blue team was about the future. The white team needed to help the company survive long enough to get there.

Janz was ideally qualified. He was a former journalist who had worked across both newspapers and online, he had some coding skills and he’d run a business. He was also temperamentally suited — clever, likeable, and with a background that gave him credibility with both journalists and commercial people. He’d become interested in the web at high school, which led to him starting an IT and business degree before switching over to journalism at the University of Queensland. He’d worked on the “Australian IT,” a Tuesday section of the Australian in the dotcom boom times, when more than a hundred pages of job ads was not unusual. By 2002 he’d been one of the original editors of News Limited’s News.com.au.

After leaving News in 2006, he had been online manager of TV production company Southern Star. And in 2007 he had shown his entrepreneurial side, launching Allure Media, which was backed by tech investment company Netus. Allure had a relatively unusual franchise model for Australia — offering localised versions of big overseas pop culture sites including Defamer, Business Insider, Pop Sugar and Lifehacker. After Netus was bought by Fairfax, Janz had consulted for a year before becoming CEO of HuffPost Australia, the joint venture between Fairfax and Huffington Post’s US owner AOL.

Hywood’s brief to Janz was something few organisations had cracked: to come up with a workable business model that would allow quality journalism to survive. It was assumed that the project would focus on how to rapidly grow the company’s sluggish online subscriptions ahead of the death of print.

Janz slipped away from HuffPo without much of a ripple. Little was said about what he would get up to in his new role as Fairfax’s director of publishing innovation. Needing a more creative atmosphere, independent of the day-to-day distractions of the Pyrmont offices, he began to build the leadership of the blue team at the shadow Fairfax office on Crown Street.

Normally there would have been industry press releases to announce hires of the calibre of Janz’s growing team. Most of the people who would run the new Fairfax were new to the company. Jess Ross, who’d run subscription marketing for the British consumer organisation Which, came on board as chief product officer. Damian Cronan, who had just led the technical build of streaming service Stan and before then had led technology at NineMSN and real estate startup Myhome, came on board as chief technology officer. Matt Rowley, who’d launched the content marketing division of Australia’s biggest B2B (business-to-business) publisher Cirrus Media, was to be chief revenue officer. David Eisman, already working at Fairfax in a strategy role, became Janz’s right-hand man, and would later become director of subscriptions and growth.

This wasn’t just some sort of glorified strategic consultancy. It was a startup. The blue team would have to build the technology needed to replace the existing platforms, and execute the plan at breakneck speed.

When the blue business took charge, the newspaper websites would move across onto brand-new digital platforms better suited to driving online subscriptions. “It was a bit like trying to change engines on a plane in midair,” Hywood recalls. “It was incredibly stressful and difficult. We had to hold everyone’s morale together to make this work. It was important that there was no politics, and that everybody involved in the white business knew they would be looked after once the changes were made.” Janz puts it similarly: “You’re trying to keep the plane flying while you’re renovating it.”

As the weeks turned into months, the blue business eventually grew to nearly fifty people, all of whom knew that one day soon they would need to walk into Fairfax’s headquarters in Pyrmont and take control of the plane. The blue team was based in an open-plan office. There was a room for holding focus groups at one end. And there was a balcony where the staff would hold Friday afternoon barbecues after growing to the point where they could no longer fit in any of the local burger joints.

At a standing meeting at 9.15am every Monday, everybody talked about what they were working on. “We needed a completely open and transparent culture,” says Janz. “There were no meetings-before-the-meetings to agree the outcome, and very little happened behind closed doors.” And on Fridays at 3.30pm the teams would share with the group the progress they had been making.

In Pyrmont, Allen Williams was kept up to date about the work being done by the people who would replace him. “Allen’s part was to keep things going until we were ready,” says Janz. “He knew exactly what was going on, and we knew that we’d be taking over the business, and we had to be ready.”

Just a few months before the blue business started work in August 2016, Hywood had told the Macquarie investment conference that it was inevitable that weekday printing would soon end. Says Janz, “The original brief was to build a digital business. We were supposed to be out of print, Monday to Friday, in 2017.” The weekend papers, which sold better and attracted more ads, would survive longer.

But as the blue team worked through likely scenarios, something else became clear — it made more sense to keep the metro newspapers than to close them. Janz says the conclusion was gradual, rather than coming in a single lightbulb moment. Closing the papers might save a lot of money but it would also cost a lot of reader and advertiser revenue that wouldn’t come across to digital. There would also be a huge loss of relevance.

“It became evident very early on that the newspapers had such scale and influence that we needed to find a way to keep them,” says Janz. “Newspapers were still such a powerful piece of people’s lives. One of the keys to the rebirth was reminding the audience that this is the thing they value, and it has such a powerful role in how they start their day. It was about taking a step back and looking at the business with fresh eyes. The exit from print was not six months away — it was a decade or more away.”

Keeping the metro papers in print would only work if yet more costs could be taken out, and the blue team needed to plan for that.

If the existence of the blue team had leaked early, particularly the fact that there would be more job cuts, it would have been a disaster for the already demoralised company. In March 2016 staff had walked out in protest at a round of 120 job cuts. Somehow, in the leakiest of industries, no gossip escaped from the blue team. “I knew it wouldn’t,” says Janz. “I trusted everyone in the group. We shared a common purpose. They wanted to do this because they were proud of the journalism and they cared about the newspapers and they did not accept their demise as a given.”

By the end of 2016 it became clear that Fairfax’s revenues were crumbling even faster than expected. Revenues had dropped from $2.47 billion in the 2011 financial year to $2.3 billion in 2012, to $2.03 billion in 2013, to $1.87 billion in 2014, to $1.84 billion in 2015. There’d been a moment when the drop seemed to be easing, with revenues almost flattening to $1.83 billion in the 2016 financial year. But over the next six months the rate of fall got worse again. By December 2016 revenues at the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age and the Australian Financial Review were down another 8.2 per cent.

What wasn’t helping was that the media agencies had heard so much about the end of print that they were turning their backs on the printed medium. Year-on-year, advertising spend on newspapers by media agencies had fallen by 25 per cent, monitoring service Standard Media Index revealed.

So the launch date was moved up to 14 February 2017, the day that the blue business would become the white business. On Valentine’s Day, the blue team walked into the offices at Pyrmont and took charge. Janz was announced as the managing director across Fairfax’s metro publishing division covering the Age, the Sydney Morning Herald and the Australian Financial Review.

Williams was given the new title of director of publishing transition. He’d be looking after the community papers. The community papers were not in Fairfax’s long-term future plan.

In a memo to staff, which was intentionally leaked to the outside world, Hywood wrote: “Chris has been overseeing the impressive product and technology development work that will be the centrepiece of Metro’s next generation publishing model. While we have considered many options, the model we have developed involves continuing to print our publications daily for some years yet.”

A week later Hywood went even further on the message that print extinction was cancelled. Not quite conceding it was a U-turn, he told investors: “We have looked at all options and while Monday to Friday can’t ever be off the table because it may well be the right thing for shareholders down the track, our view is that for some years yet, six- and seven-day publishing is the best commercial outcome for shareholders.”

Initially, the arrival of the blue team seemed like just another round of bad news to the staff. To make the plan viable, more jobs would need to go from the newsrooms to save another $30 million. Announcing the cuts on 5 April, Janz said, “With the proposed changes to the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age, Brisbane Times and WA Today newsrooms announced today, we will have completed the major structural editorial changes required to secure our metropolitan mastheads. The primary focus of Fairfax Media over recent years has been to lay the groundwork for the creation of a sustainable publishing model. We are now within reach of that goal.”

Unsurprisingly, when Janz talked to the newsroom, he was met with hostility. It looked like just one more round of cuts. “I told them that if nothing changes, we would be making redundancies every six months,” says Janz. “But what we were doing would be the last one that’s ever going to take place. I stood up and they were hurling abuse. The gut reaction was that they’d heard it all before.”

When the detail of the cuts — which would include another 125 job losses — was revealed at the beginning of May, most of the journalists in Sydney and Melbourne voted to go on strike for a week, wiping out most of the company’s coverage of the federal budget. By relying on wire copy and covering the news themselves, management still got the papers out.

During the strike, Hywood spoke again at the Macquarie investment conference, a year on from suggesting that weekday printing was coming to an end. “We respect our staff for the passion they have for independent, high-quality journalism,” said Hywood. “We share it — but we know what it takes to make our kind of journalism sustainable. Passion alone won’t cut it.” For the rest of the decade, Janz kept his promise. It was the last of the redundancy rounds. •

This is an edited extract from Media Unmade: Australian Media’s Most Disruptive Decade by Tim Burrowes, published by Hardie Grant ($34.99).