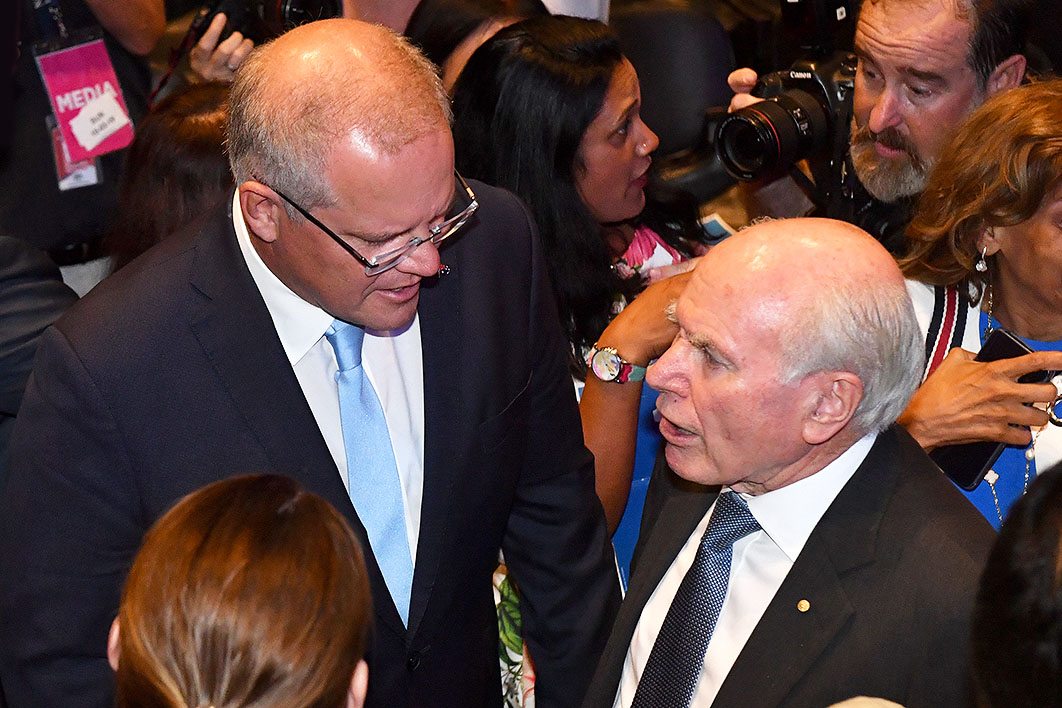

When Scott Morrison put trust at the centre of this year’s election campaign, he was no doubt aware of how slippery the concept can be. It was certainly a flexible notion in the hands of John Howard, who famously told a group of journalists back in August 2004, “This election, ladies and gentlemen, will be about trust.”

It’s easy to forget how audacious that statement seemed at the time. A few weeks earlier, forty-three former defence and diplomatic figures had charged the government with having deceived the public about the threat posed by Iraq’s elusive weapons of mass destruction. Not only that, but it had boosted the threat of terrorism in the process. Then a former government adviser revealed how the prime minister had known before the 2001 election that the “children overboard” incident — a centrepiece of that year’s Coalition campaign — was unlikely ever to have happened.

A few days later, when the Morgan Poll asked which party leader was “more honest and trustworthy,” Mr Howard managed just 28 per cent. “Credibility and truth have emerged as the prime minister’s Achilles heel,” reported the Labor Party’s pollsters, and the phrase was picked up as the headline for a column by the normally sympathetic Glenn Milne in Melbourne’s Herald Sun. According to Agence France-Presse, the prime minister was facing “the fight of his long political life.”

The genius of Howard’s campaign was to take “trust” in the conventional sense — the thing he and his government had so manifestly lost — and turn it into a simple issue of economic management. Interest rate fears and opposition leader Mark Latham’s obvious inexperience moved to the centre of the campaign, and the Coalition won convincingly.

What goes around…

If they get back into government, Scott Morrison and his colleagues might keep in mind what happened next. The first sign of trouble came on election night, when finance minister Nick Minchin told ABC viewers that the strength of the vote had given the government a “clear mandate” to sell the rest of Telstra. The Australian joined in on Monday morning with more mandates: for employer-friendly unfair dismissal laws, looser media laws and tighter criteria for disability benefits.

Viewers and readers probably assumed they’d missed the debate about these issues during the campaign. But they would have sought in vain for any mention of Telstra, media laws or disability benefits in the Coalition’s policy platform, or in the prime minister’s main pre-election speeches — at the campaign launch and at the National Press Club — or even, except fleetingly, in the media coverage. The platform, Our Plans for Australia, included just a brief reference to relaxing unfair dismissal laws (the policy destined to become the much more ambitious WorkChoices), ninth on a list of policies for “supporting small business.”

With control of the Senate for the first time since 1980, the Coalition pushed ahead with the policies it hadn’t wanted to talk about. Telstra was fully privatised, WorkChoices introduced, media laws loosened and disability payments tightened. Policies nurtured for years but never especially popular were implemented at last.

At the 2007 election, three years after it had campaigned on trust, the Coalition’s shortcomings and internal divisions caught up with it. Weighed down most of all by WorkChoices, it lost the 2007 election and the prime minister lost his seat.

Scouring the board

One person likely to be watching how Scott Morrison fares in the trust stakes is David Butler, for many years Britain’s best-known psephologist, who is the subject of a new biography, Sultan of Swing, by journalist Michael Crick.

Sir David first appeared on a British election-night broadcast in 1950 and went on to cover every national election until he retired from Oxford in 2010. He joined Twitter for the 2017 British election campaign and hinted that he might be back for another. (If the Conservatives hold on until 2022, he’ll be ninety-seven.)

He first came to Australia with his family in 1967 to spend the second half of the year as a visiting fellow at ANU. He quickly became a fixture in the media, famously telling Mike Willesee on the ABC’s This Day Tonight that prime minister Harold Holt was “not quite up to the full scale of the job,” and he returned to Australia for every federal election between 1969 and 2001. On election nights, as Ian Warden wrote in the Canberra Times in 1987, his “eyes (behind thick glasses) scoured the giant tally board for any hint of a swing to anyone which might be a harbinger of some national trend. He was like some old sea-dog, examining the firmament for some portent of a storm.”

Butler influenced Australian political science in many respects, but the traffic in ideas was two-way. With Malcolm Mackerras, he developed Australia’s first election pendulum, based on the “swingometer” he’d refined for the BBC’s election-night coverage in 1959. Back home, he argued that Britain needed an equivalent of the Australian Electoral Commission (they might have a commission now, but it’s not much like ours) and could learn from our relatively speedy electoral redistribution process.

My favourite scene in Sultan of Swing, though, comes in February 1950 when Butler is summoned to Winston Churchill’s home one night to be grilled about an article he’d written for the Economist. An election campaign is about to begin, but there is Churchill, leader of the opposition, having a long talk with a twenty-five-year-old political scientist about the finer points of predicting election results. (Churchill lost that election, but was back in 10 Downing Street the following year.)

Who don’t you trust?

It’s hard to say for sure whether Bill Shorten read Rod Tiffen’s Inside Story essay on the long decline in the power of the Murdoch papers, which we published back in 2015, but the Labor leader’s recent comments suggest it can’t be ruled out. Readers of Murdoch’s newspapers are becoming fewer and older, the essay showed, and polling by Essential Research had revealed that the mogul’s tabloids were rating ever more dismally on the question of — yes — trust.

“In August 2014,” Rod wrote, “51 per cent of Daily Telegraph readers said they trusted it; for the Herald Sun the figure was 53 per cent and for the Courier-Mail 54 per cent. In other words, nearly half their own readers don’t trust these papers.” But there was worse: “in three of the five polls, the Telegraph’s level of trust dropped below 50 per cent, and after the 2013 election it dipped to 41 per cent.” The latest Essential poll on the topic, in October, had all the Murdoch tabloids on less than 50 per cent. •