“What does he think of this? What does he think of this now?” Jean-Paul Sartre, reading the newspapers in the weeks after a car crash killed his estranged friend Albert Camus, put well the impact of a singular kind of intellectual bereavement. Many who knew Fred Halliday, the analyst of international affairs, must in their own way have echoed the thought after his death in Barcelona in April 2010 – and perhaps continue to do so.

As events unfolded in the Middle East, an element of synchrony came to sharpen the loss. Halliday was an extraordinary public intellectual. His work of four decades covered many fields, as the titles of his twenty books indicate: among them are Arabia Without Sultans, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, The Ethiopian Revolution (co-authored with Maxine Molyneux), The Making of the Second Cold War, Revolution and World Politics, and Two Hours that Shook the World.

Moreover, its wide range was combined with great social depth. Halliday’s mind was capacious and forensic, his lens panoptic and microscopic. (“The personal is the international” was one of his many aphorisms.) His rights-based universalism, reached via a lengthy marxisant prologue, was never arid, and was watered by immensely rich and loving empathy with national and local particularities, from architecture and dialect to cuisine and humour. Never was this more true than in connection with his beloved Yemen, one of his book-length studies being Arabs in Exile: The Yemeni Community in Britain. (“My one remaining ambition in life,” he once wrote, “is to have a bookshop, library or street named after me in Yemen.”)

Halliday was also unafraid: ready in argument to express uncomfortable truths and test lazy assumptions, bold in rethinking his own ideas and absorbing new ones, but also prepared to contest breaches of fundamental principle from whatever source. Two very different examples of the latter are his defence of Kuwaiti sovereignty following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of the emirate in 1990, which was reinforced by inside knowledge of the nature of the Ba’athist dictatorship, and opposition to his own London School of Economics accepting money from the Gaddafi coffers in Libya. The first caused a permanent breach with many former allies, the second – which emerged posthumously – fuelled a burgeoning scandal (though Halliday’s forewarning sought only to uphold the LSE’s integrity and self-interest).

Such stances were far from contrarian. Halliday’s compass took its bearings from the ground, “the analysis of what actually happens,” and from solidarity, “the shared moral and political value and equality of all human beings, and of the rights that attach to them.” Whether the topic was Cuba or Libya, terrorism or 1968, his work matched detailed familiarity with independence of political judgement. His grasp of complex subjects, and his ability to explain them clearly, informed his contributions in every forum: from seminar room and lecture hall to journal and broadcasting studio, and in hundreds of articles and dozens of chapters on top of those books. Halliday was one of those rare people who appear a lot on the intelligent media while never becoming a “media figure,” his voice – lucid, informed, careful, robust, educative, morally serious – a force for reason as well as the healthy contention he loved.

Behind it all lay Halliday’s inimitable presence, or anima, which flourished in those public or semi-public arenas where a wealth of personal memory, cultural reference or vernacular insight made bonds and gave his ideas sparkling life. The insights had been earned, not merely acquired, by a lifetime’s vigour, curiosity and empathy: learning those languages, travelling and listening (and he was as good a listener as he was a linguist), looking behind; what he liked to call “doing the work.” (Halliday, who spoke nine languages fluently and others more than passably, including several dialects of Arabic, was fond of saying, “You get to speak a language the way you get to swim: learn a few basic moves, and then dive in!”) Whether a solitary study, a warm cafe, a bubbling salon, a teeming street, a yawning lecture room, or a desert or mountain night among men with guns – Halliday was at home in the world, and capable, time after time, of turning that faculty into enlightenment.

These textures were revitalised when, after two decades at LSE’s department of international relations, he began to shift base towards a “new professional triangle,” the IBEI/CIDOB/CCCB research institutes in Barcelona, a city whose genius for conviviality matched his own. Carmen Claudin recalls his arrival from the airport as a one-month guest researcher: “He came directly to CIDOB, as we had agreed and, coming through the door, before as much as saying hello, he exclaimed with a knowing smile, ‘I think I could live in this place!’”

The incremental move sealed Halliday’s recovery from an illness partly induced by overwork during the post-9/11 period. A new balance was reflected in several books, including The Middle East in International Relations, 100 Myths About the Middle East, and Shocked and Awed: How the War on Terror and Jihad Have Changed the English Language, and in prolific media output, including columns in the Barcelona newspaper La Vanguardia and frequent essays in openDemocracy. The Latin America historian James Dunkerley, latterly a neighbour in London’s Tavistock Square (where Halliday stayed when working in the city), offers a characteristic, and suitably newspaper-related, vignette from this period:

He liked to read the morning papers in the beautiful garden centred on the statue of Gandhi and dedicated to the cause of peace. Always jovial, even when palpably suffering, he would regale me in his burnished baritone with the latest news from Bishkek, ask about the balance of forces in Quito, and deconstruct conspiracies in Sana’a.

Barcelona’s benign influence on Halliday leavened the coincident darkening of world politics, not least in and around Iraq following the United States–led invasion of 2003. Much of Halliday’s reputation had been built on prodigious engagement with the Arab and Iranian worlds. He came to see their modern experience of revolution, dictatorship and war in terms of a “greater west Asian crisis,” a term he coined in 2001, denoting the impact of post-9/11 geopolitics on “a wide arc of nation-states – the Arab world, Israel, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan.” In the same period, ideas forged in the preceding decade found fresh relevance: ideas about the modernity of nationalism and of the Middle East itself, about the fates of solidarity and about “patriarchy with guns.”

In 2010–11, the uprisings of the “Arab spring” – beginning in Tunisia, then spreading to Egypt, Libya, Bahrain and Syria, but leaving nowhere untouched – opened tantalising hopes of a historic turn towards freedom and democracy in the region, many soon to be drowned in blood. A year earlier, Halliday had written about the student-led protest wave in Iran after the presidential elections. No one was better qualified to make sense of these new events – their origins, character, dynamics, and place in the global map. Yet when people looked around, he was gone.

A natural consequence of death is to invite attention to a person’s whole life. In Halliday’s case, the first of three commemorations held in London, attended by a large crowd at London University’s Senate House, suggested that his intellectual and ethical wellspring was intimately linked to his family and social milieu. (The other two events were a panel discussion and day-long seminar focusing on his work, both at the LSE.)

Simon Frederick Peter Halliday was born, the youngest of three brothers, in Dublin on 22 February 1946 – the very day, as he once noted, that the American diplomat George Kennan despatched his “long telegram,” the cold war’s formative document, from the United States embassy in Moscow. (The text was published early the following year as “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” under the pseudonym “X,” in Foreign Affairs. Halliday would interview “Mr X” at Princeton in 1995, as part of a series of conversations with strategists of the era; the others were Paul Nitze, Henry Kissinger, Robert McNamara and Robert Gates.) He was brought up in the town of Dundalk, on the border of a politically divided Ireland, which was often a refuge or base for Irish Republican Army operatives (as in the stuttering “border campaign” of 1956–62). His father Arthur was from Yorkshire in England, the caring owner of a shoe factory, and of Quaker background; his mother Rita was Irish and Catholic.

These dualities may account for a lot. Halliday observed of his hometown in 2004: “The whole agenda of international relations is there: state formation, frontiers, revolutionary struggle, nationalism, industrial rise and decline, illegal transnational flows, environmental damage, and perhaps now a bit of international cooperation.” Yet it’s worth recalling too that such “mixed” backgrounds, in politically charged contexts, often result in demonstrative nativism. (Ireland has prominent examples, as have Scotland and Wales, to name only those.) Halliday himself was always highly critical of ultra-nationalism, in Ireland as elsewhere. He also had a ready answer to any safety concerns while on the road: “I was brought up in Dundalk!”

During his early years, Ireland was establishing itself in the international arena, becoming a republic in 1949–49 and joining the United Nations in 1955. Frank Aiken, the pioneering foreign minister of the 1950s–60s, carved an activist foreign policy that included championing the rights of beleaguered Hungary, Tibet, Algeria and Taiwan, and bold advocacy of pacts over nuclear weapons and the Arab–Israeli conflict. The patriotic internationalism represented by Aiken, whom Halliday greatly respected, may also have exerted an influence.

The closing speaker at the Senate House was Halliday’s elder brother Jon, whose books include a biography of Mao Zedong, co-authored with Jung Chang. His contribution ended on a moving note by quoting Fred’s reference to him on a past occasion, using an affectionate Irish phrase, and then, very quietly, returning the words. “Here’s to me sound man.” The bonds between home and world never seemed so close.

Halliday’s schooling was at Ampleforth, a Catholic college in north Yorkshire with roots in the nearby Benedictine abbey. Edmund Fawcett, a co-pupil, recalled Fred, around the time of China’s invasion of Tibet, studying a Tibetan-language textbook to try to grasp more of what was happening. A reference backing his Oxford application in 1963, quoted in a thoughtful survey by Adam Roberts for the British Academy, described him as “a most conscientious person of high ideals and admirable performance.”

Halliday stood out even amid the student ferment of mid 1960s Oxford, where he gained a first-class degree in philosophy, politics and economics and, as political editor, wrote for the student magazine Isis. His invitation to Francisco Caamaño Deñó, the exiled ex-president of the Dominican Republic, in 1966 is an example of his outward-facing maturity at this time. Their meeting had a profound impression on Halliday, whose later research produced a valuable book (“heteroclite,” in his own description) on Caamaño and this moment in the country’s history.

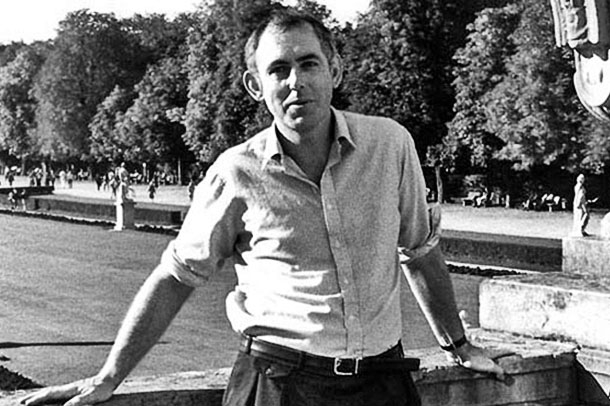

There followed more study at SOAS, work in London’s innovative radical press, membership of the editorial board of the influential New Left Review, or NLR (which would last fifteen years, until 1983), a translation of Karl Korsch from German and an editing of essays by Isaac Deutscher, and extensive travel, including for his books on the Arabian peninsula and Iran. All were underpinned by vital partnership with the international sociologist Maxine Molyneux. What’s notable too is that for all the atmosphere of the time and Halliday’s political leanings, his travels were at heart those of an honest, empathetic inquirer, not a “tourist of the revolution.” (A photo of him sitting on the ground and tapping on a typewriter among his Dhofar radical hosts is emblematic.) The Harvard historian Roger Owen, a decade older, said of Halliday that “he always seemed to have been somewhere first, to have summed up the situation there before I or those with similar interests had even begun to put a few first incoherent thoughts about it together.”

Amsterdam’s Transnational Institute and Washington’s Institute for Policy Studies gave important sustenance at a time when the “international left” seemed more than a chimera. But the broader authority of Halliday’s work was reflected in 1984 with his appointment (against some internal opposition) to a lectureship at the LSE, and later a chair. Thus began a mutually productive association of over two decades. (In 2015, the LSE’s Language Centre inaugurated an award in his name.) He taught, supervised and mentored generations of students, played a leading role in the international relations department, and encouraged younger scholars such as Katerina Dalacoura, Umut Özkirimli and many others towards professional achievement. His emphasis on the centrality of gender to the field, as in Rethinking International Relations, had a keen influence on the discipline.

Dalacoura, also a speaker at that London meeting, began in the present tense by saying that Halliday “influences us by what he does and who he is as well as what he writes. We were it, part of his wider engagement with the world. He made us think, he was without discrimination, and liberal with time and praise. His generosity of spirit will stay with me more than anything.”

In a fine valedictory, his colleague Christopher Hill noted the wider respect in which Halliday was held (he “carried personal, intellectual and political weight, and thus could never be taken for granted”). He saw the department not “as a home, in which to retreat behind closed doors,” Hill said, but as “a castle, from which he could venture out,” including “to the world of policy debate in which he continued to join so vigorously.”

The point carries weight. For Halliday, the instruments of enlightenment, used well – reason, dialogue, research, analysis, knowledge-based argument – were also means towards a better world. James Dunkerley remembers an unusually harmonious NLR party to mark Halliday’s unexpected (and in a red-baiting redoubt of the press, scandalous) elevation to the LSE. “What does it mean, Fred?” he asked. “It means I have twenty-six years to make a difference!”

The years since Halliday’s death have seen excellent assessments of his work by academic colleagues of the calibre of Stephen Howe, David Styan, Toby Dodge, and Alejandro Colás and George Lawson, as well as Susie Linfield’s fine essay in the Nation. In addition, scrupulous work by a small team at the LSE, led by Benjamin Martill, has catalogued Halliday’s academic bibliography, almost a quarter of whose eighty pages is composed of unpublished manuscripts. It is open to researchers, as is Halliday’s personal archive, a separate project also under the LSE’s auspices.

These are foundations of what might one day become an intellectual–intellectual biography, which by default would also encompass the history of the post-1945 world (and several of its tributaries, including the cold war, communism, jihadism, and the left, and ideas of revolution, nationalism, and solidarity.)

Yet there is also a sense that in an international arena threatened by insecurity, violence and extremism of attitude, Halliday’s work and example could contribute far more than they are being allowed to do. At any rate, the rational principles to which he gave large-minded and grounded expression – above all the “unceasing belief in universal values” he shared with an ally, Maxime Rodinson – are acutely relevant.

Such universals, moreover, are not at odds with the particular, but crystallised in it. Halliday had little use for “identity” or “tradition,” far less essentialist, relativist or postmodernist conceits. The pithy sparks lighting his trail included: “No nation is older than the oldest living person claiming to be a member of it,” and “When I hear the word ‘community’ I reach for my exit visa!” Among his list of “the world’s twelve worst ideas,” number four was “The world is divided into incompatible moral blocs or civilisations.” Politics and culture are not the same. Separate them, reinstate politics, and much could follow.

Halliday’s last article before the onset of his final illness was about Barcelona. It describes a lively debate, or tertulia, he took part in on Catalonia’s TV3 channel, then moves outwards. While attentive to the city’s “dark” and “grey” worlds, the tone is life-affirming:

This is the Barcelona, above all, that I have come to know and love: the Chilean waiter in Sant Gervasi who teaches me left-wing slogans in Mapuche justifying mass land seizures; the Moroccan family I met on the beach at Barcelonera, who speak only Berber and Catalan; a sprightly gentleman of some eighty or more years, sipping coffee with his wife in a bar next to the offices of La Vanguardia, who, when I drop my pen, immediately jumps down and picks it up, and then presents his card, identifying him as the president of the Catalan Association of Republican Aviators, a veteran not only of the civil war, but, in exile, of the French air force as well; an Australian co-author, long resident in Papua New Guinea, now a leading translator of Catalan literature, ensconced in her book-lined eighteenth-century flat in the Born, with the volumes of Joan Corominas as backdrop; a man in his shorts, alone on the Carrer de Comercio on a torrid Sunday afternoon, singing the “Mediterráneo” of Joan Manuel Serrat; my Icelandic designer friend who brings a small bottle of Brennivin, a 40 per cent proof northern liquor from her country; the Filipino waiter who, on advising me of the best meat dishes in his country, after indicating which can be taken with chicken, pork or beef, then whispers that, of course, the best is dog; an Italian student, expert in Romance languages, and now working on Occitanian poetry, who consults me on the possible Arabic roots of this vocabulary; and my Catalan language teacher, a Palestinian translator from Los Angeles, to whom I have awarded the nickname Abu Tarjoma, “the father of translation,” whom I meet once a week for coffee and an exchange of linguistic and intercultural anecdotes. And many more.

That this comes from a man of deep political seriousness, whose life’s purpose was to understand the world in order to change it, only adds another layer. For once, forget the evidence. The world has not seen the last of Fred Halliday. •