Especially in his later life, Ken Inglis pondered how it was that he found his way from Tyler Street State School to an academic career. The question was at the back of his mind as he exchanged emails with contemporaries, followed the suburb’s changing fortunes and recalled formative moments in his childhood. One such moment occurred in 1937 when the teacher of fourth grade carefully wrote the word “noun” on the blackboard and then explained its grammatical function. Some days later Miss Kinnane followed that revelation with another, equally arresting — “verb.”

Ken had a preference for nouns and verbs, though he was no slouch with adjectives and adverbs, and appreciated the effects that could be achieved by variations of structure and rhythm. An early influence was George Orwell, whom he discovered through the 1945 essay “Notes on Nationalism.” The rules of composition that Orwell laid down in the following year in an essay on “Politics and the English Language” were already apparent in Ken’s writing: never use a stale figure of speech; never employ the passive when the active is available; never use an unnecessary word, or a long one when a short one will do, or jargon when there is an everyday English equivalent. Orwell added a sixth rule — to break any of the above rather than say or write anything outright barbarous — though it is hard to find instances of that escape clause in Ken’s prose.

He grew up in a house with books and was an avid reader of the press from boyhood. Another writer who influenced him was the American journalist A.J. Liebling, whose contributions to the New Yorker spanned politics and popular culture, and who also wrote a pungent monthly survey of the American press. Ken later sent a copy of his book The Stuart Case to Liebling in homage and was delighted to receive an acknowledgement.

Ken’s interest in journalism was established when he transferred from Northcote High School to Melbourne High in 1945 so that he could progress from his Leaving certificate to the new qualification of Matriculation; it was in his second year of Matriculation studies in 1946 that he resurrected the school newspaper, the Sentinel. Already fascinated by broadcasting, he also worked after school on the radio program Junior 3AW.

Towards the end of the year his father arranged an interview with the editor of the Age. Harold Alfred Maurice Campbell — generally known as “Ham,” though he became Sir Harold in 1957 — was a courteous and kindly man, yet unfamiliar with the Sentinel. “Oh, we all do that,’ he said when Ken referred to his editorship, clearly thinking it was another of those school magazines that record deeds in the classroom and triumphs on the sporting field. The sixteen-year-old was too shy to explain that his was a fortnightly publication of much greater substance and purpose.

In any event, Campbell said that it was not a good time to be embarking on a newspaper career when so many able reporters were returning from war service; he led Ken to understand that distinguished military correspondents were reduced to emptying wastepaper baskets. So the youthful aspirant’s hopes were dashed. “If the Age had taken me on as a journalist in 1946,” he subsequently stated, “I’d have gone there.”

By this time there was another possibility. Northcote High did not teach history beyond the first few years, but at Melbourne High he was able to pursue a rich variety of history subjects as well as literature and French. Too young to go to university, he did a second year of Matriculation, this time winning a general exhibition and sharing first place in the state for English literature. A friend who accompanied him from Northcote to Melbourne High had meanwhile commenced an arts degree as a resident of Queen’s College. Ken visited him there in 1946 and was persuaded to sit for a resident scholarship. Having secured one, he embarked in 1947 on an honours degree in history and English, and found his vocation. As he recalled nearly fifty years later in a retirement address, “From almost the moment I arrived at the university, I knew that was where I wanted to spend my working life.”

Having obtained a first in his combined honours degree in 1949, Ken became a temporary tutor in history in 1950, senior tutor in 1951, assistant lecturer in 1952, and in 1953 was appointed to a tenured lectureship. Meanwhile he took over a history of the Royal Melbourne Hospital from Max Crawford in 1952 and submitted it as an MA thesis in the following year as he began doctoral studies at Oxford.

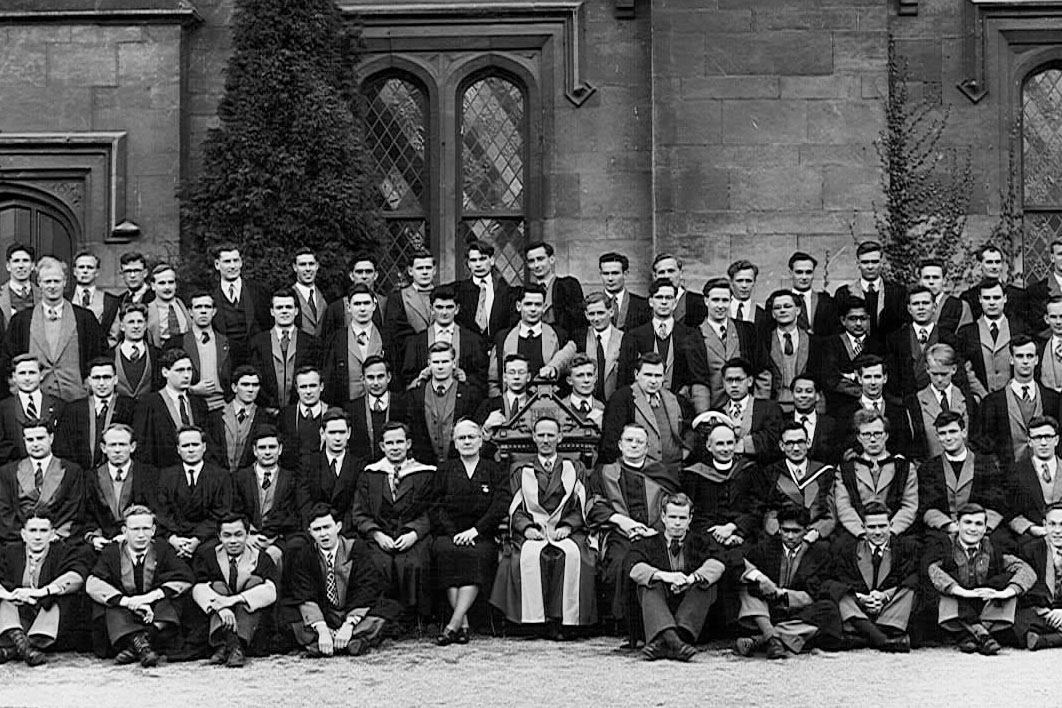

While an undergraduate and for two years after graduation he was a resident of Queen’s College, the third of the men’s residential colleges attached to the university and at that time probably the most lively. Contemporaries included Geoffrey Blainey, Herb Feith, Sam Goldberg, Murray Groves and Arthur Huck; the economists Max Corden and Murray Kemp; and the legendary George Nadel, a Dunera boy of boundless ambition whose silhouette was always visible through the curtain of his study window, working at his desk, until someone discovered he had imitated Sherlock Holmes and rigged up a dummy.

Beyond College Crescent, Ken was involved in the university film society, theatre and music but not politics until 1949, when he helped form the ALP Club as an alternative to the communist-dominated Labor Club. This coincided with his joining the Student Christian Movement, or SCM, after his boyhood Presbyterianism had lapsed. It was here that he met Judy Betheras, a philosophy student. They married in 1952 and had their first child shortly before leaving for Oxford.

Ken’s religious interests informed both his doctoral research and his subsequent understanding of Anzac remembrance. They also stimulated some of his first public statements of what he believed. He was attracted to the SCM, I think, because of the way it bridged faith and reason. Arthur Burns, that gifted but wayward ordained academic who returned from England to the history department in 1949, introduced him to the new theology with its rigorous reading of the scriptures and commitment to public engagement. “I am a democratic socialist and a Christian,” Ken told an SCM conference, and said that he shared communists’ anger at the economic organisation of capitalist society but could not subordinate his conscience to “the God of the party.”

The cold war had brought the world perilously close to destruction and it was the zealotry of both camps that created the danger. In a series of articles written for the Victorian branch of the Institute of International Affairs, Ken refuted the polarised claims of the combatants in the Korean war and other flashpoints in the region. “We live in a secular age,” he preached in the Queen’s College chapel in 1950, an age that saw the forms and adherents of Christianity falling away. Ken’s was a form of Protestantism that affirmed the personal conscience of the believer, “the voice of God” finding expression through the individual bearing witness in public endeavours.

He was also involved in student journalism. We find him in the pages of Farrago reviewing the 1949 Melbourne University Magazine, edited that year by Max Corden and Henry Mayer, who were destined for distinguished careers in economics and political science. They were a mettlesome combination — Max said that at one point he challenged Henry to a duel — and Ken observed that their arguments could have been resolved by both turning their weapons on the cover designer. When he and Murray Groves became editors of the 1950 edition they immediately approached William Ellis Green, better known as WEG, the chief cartoonist for the Melbourne Herald, to provide a more arresting cover. The 1950 Melbourne University Magazine was redesigned in a smaller format based on the lively British pocket monthly Lilliput, and the editors sought contributions that displayed “passion and a point of view.” “Hack-work,” they warned, was “unacceptable.” It was here that A.D. Hope’s Dunciad Minor had its first outing.

One of Ken’s early contributions to the Age was aimed at the hack-work that appeared in its Saturday literary section. Assuming the identity of the Rev T.J. Ransome, he submitted a lengthy essay on “The Fascinating Bee,” strewn with bogus literary allusions and sonorous analogies. “Poets have sung of it, and philosophers seeking to discover the elusive truths which, if found and believed, would enable men to live in concord, have been drawn to study and wonder at the harmony of the hive.” It appeared with a photograph of busy bees, and Ken worried when he became a regular contributor to the newspaper that someone would say, “I see you’ve fooled them again.”

The first of his Age pieces that I’ve been able to find (not all are identified) was a review of two recent productions of Elizabethan plays in 1949, and he continued to write on literary and historical publications. But as early as 1950 he wrote a striking discussion of the English comedian Tommy Handley, who had died in the previous year. Handley’s weekly radio program, It’s That Man Again, was recalled for its “verbal cartooning” of wartime sacrifice and postwar austerity, “conjuring up a crazy world in which his listeners could forget their worries for a half-hour.” Ken drew attention to the distinctiveness of Handley’s humour, noting that he did not rely on a stooge, as American comedians such as Bob Hope and Jack Benny did. “It was a craziness,” he observed, “made possible by the medium of broadcasting.”

He also contributed to a short-lived quarterly, the Port Phillip Gazette, modelled on the New Yorker. An early piece for its equivalent of “The Talk of the Town” related a pipe-smoking contest at the Town Hall where a field of twelve each loaded 3.3 grams of tobacco (weighed out by the city council’s weights and measures department) and were given two matches to light up. At ninety-four minutes and thirty-five seconds (measured by technicians from the Chronological Guild of Australasia), the record held by a native of Schenectady in New York, which was the headquarters of the International Pipe-Smoking Fellowship, fell and a veteran pipeman, Bill Branfield, finally stopped puffing after 107 minutes and nine seconds.

Ken’s deadpan report concludes that it might have been as well to have the weather bureau people present to check the humidity in case Schenectady ruled that local conditions gave too much assistance — and I concluded that this must be another hoax until Trove provided newspaper reports of the event. The Age’s reporter asked the winner if he was concerned by the British Medical Association’s recent warning against smoking, to which Bill Branfield replied, “BMA, never heard of ’em.”

It was probably inevitable that Ken would go to Oxford, as so many Melbourne historians did. By my count, eighteen of them were there in the postwar decade, against three who pursued postgraduate studies in London, three in Cambridge, one at Columbia, one at Smith College and one at Harvard. It is noticeable also that three of the five women, Dorothy Crozier, Pat Gray and Dorothy Munro (Shineberg), went elsewhere to train in anthropology, sociology and Pacific history. The men followed a well-beaten disciplinary track, whereas the women felt it necessary, or perhaps desirable, to be more adventurous.

“No Melbourne person, particularly a history graduate, need feel a stranger in Oxford,” Owen Parnaby wrote in 1950 after Hugh Stretton, Laurie Baragwanath and Sam Goldberg welcomed him and his partner Joy upon arrival, and soon John Legge and Frank Crowley called on them. The Australian colony at Oxford sent back intelligence on college admission practices and expenses to guide those who were to follow; Max Crawford provided the references, helped secure the scholarships and on several occasions obtained additional money for those who needed it. When he noted at a departmental farewell to the 1951 contingent that John Mulvaney was headed for an archaeology degree at Cambridge, he added, “We have nothing against Cambridge, it is just that we don’t know it.”

There was a joke among the Melbourne graduates who taught in the history department and undertook a local master’s thesis while preparing for their time abroad: “Which aspect of the Australian labour movement are you going to write your MA on?” The expectation attests to the progressive sympathies of staff and students, many of whom cut their political teeth in the Labor Party, if not the Labor Club. Ken expected to do the same but was happy to take up the hospital history, for he was interested in the way Australians had adapted social policies and institutions to their circumstances.

In formulating his doctoral research project he was strongly influenced by Alan McBriar, who returned from Oxford at the end of 1948 after completing a DPhil thesis on Fabian socialism. A gentle and witty man with a memorably distinctive laugh, McBriar had abandoned his wartime membership of the Communist Party (to which he had recruited Amirah Gust — later Amirah Inglis — even though her parents were party members) but remained “wistful” about the Marxist legacy. Ken tutored for Alan and gave his first few lectures under his sponsorship. On Alan’s advice Ken wrote in 1952 to his former supervisor, G.D.H. Cole, asking for guidance on a suitable topic among the social movements of the late nineteenth century. He had the Socialist League in mind, but Cole advised him that a man called E.P. Thompson was working on that and suggested he might instead consider the arguments between socialists and the philanthropic organisations, or perhaps the endeavours of the Labour Churches and other ethical movements of the period. This combination of socialism and religion sparked an interest, and soon Ken settled on a study of “religion and the social question, c.1880–1900.”

Admission to Oxford was through a college and Ken chose University College, which made few demands on its postgraduates, since he was a married man with a baby and would live in rented accommodation in Summertown. Initially he and Judy had the company of his sister Shirley, who interrupted her Melbourne degree in English for fifteen months abroad, first as a governess in Paris, then as a waitress at the Lyons buffet at Wimbledon for the tennis, and finally working in Oxford (she borrowed Ken’s gown to sneak into lectures). His friends Jamie Mackie and Kit McMahon were pursuing undergraduate degrees as college residents and were more fully exposed to college life. Ken, who hated exams, thought they were the heroes. Judy chose the examination path, though, for a postgraduate diploma in anthropology — the course that Murray Groves had taken and Shirley Inglis would follow. The Inglises were supported by a scholarship Ken had obtained from the Australian National University, which during its early years sent Australians from across the country abroad to obtain higher degrees. The catch was that the scholarship lasted just two years.

At least initially, he found Cole a satisfactory supervisor. In an early letter back to Crawford, he said Cole knew “an enormous amount about the subject” and professed great interest in it. That favourable impression did not last. Cole was in his mid-sixties and in poor health. He came up from his London residence for just a few days each week during term, and was always busy. When Ken gave him a draft chapter, he would return it promptly but with little comment on its substance. Most worryingly, Cole failed to see what Ken was trying to do, for he was an old-fashioned institutional historian with little interest in a social history of religion.

Ken was enrolled in the faculty of divinity rather than modern history (for his topic was deemed too modern to be history) and no seminars were given in modern history except for one on imperial history, which did not interest him. He found his stimulus among other doctoral students at a cafe near the Bodleian Library. Over grey coffee and Woodbines they would compare their supervisors. An American remarked of Cole’s minimal assistance that “Ya put in a nickel and he plays.” Chushichi Tsuzuki spoke warmly of the assistance he received from his supervisor (and mine at Cambridge) Henry Pelling, and Henry would take a keen interest in Ken’s work. Peter Cominos, another American, gave glowing praise to Asa Briggs, the unstuffy, energetic and pioneering young reader in recent social and economic history. Ken had read Briggs’s short sketch 1851, published by the Historical Association in 1951 and foreshadowing his 1954 re-evaluation of Victorian People. Through Cominos, Briggs invited Ken to drop in and discuss his research. “He saw at once what I was trying to do.”

The principal outlet for Ken’s journalism during this period was the Sydney-based magazine Voice. It began at the end of 1951 as AIM, the Australian Independent Monthly, an anti-communist, social democratic forum aligned with the Fabian Society and Workers’ Educational Association, which attracted contributions from Heinz Arndt, Macmahon Ball, John Burton, Sol Encel, Peter Russo and a young Don Dunstan. Ken’s first recorded contribution came in 1954 after he, Murray Groves and Kit McMahon attended a conference in Brighton organised by the Quakers, where the successor of the jailed Jomo Kenyatta defended the nationalist uprising in Kenya. It was a sympathetic but measured report of the violent insurgency.

That was followed by an equally sympathetic but more stringent review of a book by Adlai Stevenson on world affairs, in which Ken drew attention to the way that “Mr Stevenson’s language” went “foggy” when the politician prevailed over the egghead. A subsequent account of Moral Re-Armament made the same point: “Ideology is MRA’s favourite word. It is modern, versatile, and sounds solid. Again and again it is used to introduce a string of commodious nouns and adjectives” that remained airy and rhetorical generalities. Finally, in 1956 he wrote a “London letter” on the displeasure of Geoffrey Fisher, the archbishop of Canterbury, at the anti-apartheid activities of Fr Trevor Huddleston in South Africa, contrasting the “diplomacy of Dr Fisher” with the decline of his church’s membership.

I say finally because a London letter had appeared in Voice in September 1953, just as Ken arrived in England. It discussed the division in the British Labour Party between the Bevanites and the “powerful trade union bosses” and was followed two months later by a discussion of the BBC. The author of these and subsequent London letters was “Preston,” a pseudonym that someone who went to Tyler Street State School in north Preston might have adopted. “Preston” first appeared three months before Ken left Australia, writing on what was likely to happen to Sir Keith Murdoch’s newspaper empire following his death at the end of 1952, when Rupert was studying in Oxford (it was his tutor, Asa Briggs, who broke the news to him). Then, in 1954, “Preston” wrote a feature article on the implications for the Argus newspaper of a change in the management of its British proprietors. The correlation of interests between Ken and “Preston” is marked.

By 1954 Ken’s friend Kit McMahon had taken over the London letter and soon Jamie Mackie would begin writing a regular column on “The Asian Scene.” From January 1955 “Preston” reappeared, this time as the author of reports on “The European Scene”; indeed, he was identified as “our correspondent in Europe.” We know from a letter Ken wrote to Max Crawford that he had travelled in Europe during 1955, “buzzing around France and Italy on a motor scooter.” “Preston” discussed French politics at length, but in subsequent reports he referred to time spent in Germany and Yugoslavia. This seems to stretch the resemblance too far — and I learned when speculating on the identity of this peripatetic “Preston” that he was, and always had been, the young economist Max Corden. Max worked for the Argus after completing his Melbourne degree and then proceeded to doctoral studies at the London School of Economics.

Ken did not intend to become a British historian. Rather, as many other Australians did, he thought of his research as a preparation for writing about Australia. He had no desire to stay on in England and recoiled from its class-bound distinctions — “If you did stay you would have your children talking like toffs or cockneys.” A fellowship at Nuffield College after his ANU stipend ran out was more congenial, and he taught extension classes in Kent and Gloucestershire, but he was not going to stay. In May 1955 he submitted an application for a newly established chair at Melbourne, at the insistence of colleagues there. Even after Kathleen Fitzpatrick decided not to seek it, there was little chance with John La Nauze and Manning Clark in the field; but almost immediately Hugh Stretton sent him a copy of the advertisement for a senior lectureship at Adelaide. Soon it was agreed that he would take up that appointment in the first half of 1956.

His thesis title had by this time become “English Churches and the Working Classes 1880–1890, with an Introductory Survey of Tendencies Earlier in the Century” and had grown to more than 150,000 words, for one advantage of enrolment in the faculty of divinity is that it set no word limit. Cole had little to suggest on the final draft but did invite Ken to suggest who should examine it; hence his viva with Asa Briggs and R.H. Tawney in May 1956.

Cole apologised for not seeing Ken before he departed but thought he should succeed in finding a publisher; Asa Briggs was more practical and passed a revised version of the thesis to Harold Perkin, then a young lecturer at Manchester University who was assembling a series of studies in social history for Routledge and Kegan Paul. Perkin was greatly impressed but wanted a book that would take in “the sweep of the Victorian age,” so Ken rebuilt the study to open with a survey of the failure of the churches to reach the working classes and then an examination of their efforts between 1850 and 1900. Interruptions and other tasks such as The Stuart Case delayed completion until 1962; “the trouble with contemporary history is that it goes on happening,” he remarked when apologising for a further delay. But Perkin was a patient and sympathetic editor, his series impressive and influential.

During their time at Oxford, Ken and Judy expected to return to Melbourne, where they owned their home and he had a tenured lectureship. “I’m still not used to the idea of not coming back to Melbourne,” he wrote to Crawford in July 1955. Crawford assured him that “people should not be dissuaded from moving to other places, rather the reverse.” In moving on, Ken told Crawford of what he had taken from Melbourne — and I read his tribute as something more than filial respect, for it carries with it an implicit criticism of what he had missed while in Oxford. “One of the things I’ve seen more clearly for being away from Australia,” he wrote, “is that an education as good as we were given is very rare. We knew we were in a very good history school, but we (or at any rate I) didn’t realise how rare its virtues were.” He named three of them, and all read oddly in the current lexicon of higher education: first, “to have such an emphasis on shortish periods and primary sources”; second, “to have such close relations between teachers and students”; and third, “to make its students worry about why they are studying history.” Ken went down from Melbourne but he carried those virtues with him. •

This is Stuart Macintyre’s contribution to “I Wonder”: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis, edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark, released this week by Monash University Publishing. The book will be launched on 10 March in Melbourne by Tom Griffiths (details here), with a Canberra launch on 2 April.