The economy is still okay. Wage rises are low, but jobs are booming. The budget is still in deficit, but at last it is shrinking. House prices in Sydney and Melbourne have soared out of reach of many who live there, but seem to be flattening. The global economy is going gangbusters, pushing export prices high.

What advice could Australia possibly want from a team of economists from Washington, who come down here for two weeks, talk to Treasury, the Reserve Bank and a few others, and then head home to write a report published three months later as the International Monetary Fund’s annual report on Australia and discussion of additional issues?

Judging from some of the media coverage, including today’s editorial in the Financial Review, you would think the IMF’s goal was to spruik the government’s plan for corporate tax cuts. The editorial was full of fantasies about what the IMF said: whoever wrote it obviously had more important things to do than to read the report.

Shadow treasurer Chris Bowen was closer to the mark when he claimed that the IMF report vindicates Labor’s policy to shut off the tax break on negative gearing and reduce the tax break for capital gains. The latter, at least, is an issue the report comes back to repeatedly, as it examines how to improve housing affordability and reduce the risk that a housing price crash could push Australia into recession.

In fact, the IMF report carefully avoids endorsing the tax plans of either side of politics. AAP economics correspondent Colin Brinsden summed it up perfectly: “The IMF has backed the Turnbull government’s pursuit of a lower corporate tax rate, but has again called for a broader tax reform package.”

The IMF mentions corporate tax cuts in one paragraph of a report of more than 150 pages, and only as part of a wider series of tax reforms, which is just one of six proposals to lift Australia’s growth. In order, they were:

● further increase investment in infrastructure

● bump up government support for innovation

● strengthen labour market programs to equip the unemployed with new skills

● tackle the barriers to female employment

● increase taxes on land and consumer spending and reduce them on incomes and profits

● beef up competition policies as part of a structural reform drawing on the Productivity Commission’s wishlist issued late last year.

Since the coverage has focused on the company tax debate, let’s read what the IMF economists actually wrote on that topic:

A broad tax reform package would benefit productivity and reduce inequality. The government seeks to broaden the corporate tax reduction beyond small enterprises. With Australia being a capital importer, it is appropriately concerned about the international standing of corporate tax rates. Australia’s effective average corporate tax rates are currently in the upper third among advanced economies, but the international environment is evolving. A more comprehensive tax reform has the potential to increase efficiency of the tax system, increase investment and labour demand, and reduce inequality. This would entail lowering taxes on income from mobile factors of production (capital and labour) and increasing reliance on income from immobile factors of production (land) and indirect taxes on consumption, undertaken in a revenue-neutral way. According to a comprehensive reform scenario outlined in [the IMF’s 2015 report on Australia] such a reform could raise real GDP by at least 1.3 per cent. Concerns about the regressive nature of higher taxes on consumption at a time of low wage growth could be addressed by broadening the base, reducing generous tax concessions (some of which are not means-tested or are limited), and revising the design of the income tax reform.

The final sentence might seem confusing, but Brinsden’s report, written after a briefing from the head of the IMF’s team, Thomas Helbling, clarifies that the IMF meant that rather than raise the GST — a regressive tax that falls disproportionately on lower- and middle-income earners — Australia could finance its corporate and personal tax cuts by broadening the tax base, reducing tax breaks and targeting its income tax cuts.

It’s all good advice, similar to that given to a parliamentary committee a week earlier, in forthright fashion, by Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe. It also pretty closely resembles the advice that the IMF has given in previous reports on Australia, and that many of us have been giving successive governments for years — sadly, without success.

But it does not resemble the government’s plan to cut corporate taxes, which is not revenue-neutral, but is expected to cost the budget some $80 billion in its first decade alone. There are many relevant issues in the corporate tax debate, but one of the core issues is the question of which goal should take priority: getting the budget back into a sustainable surplus, or cutting corporate and individual taxes? The IMF is saying that lower taxes should not come at the expense of the budget.

Dr Lowe made the point very clearly in his testimony. Let’s read what he had to say too:

The debate (on corporate tax rates) has moved on internationally, and it does look like there is a form of international tax competition going on. The US has moved. The UK has plans to lower its corporate tax rates, and a number of European countries do as well. And you can view this competition as good or bad. If you want lower taxes, it’s probably good. If you need to fund a budget, then maybe it’s not so good.

So whatever side of that debate you come down on, it is actually occurring, and it’s hard to ignore. In the last [2016] IMF annual Review of Australia, they noted that relative tax rates were something that did influence capital flows… We mightn’t like it, but we can’t ignore it.

Another point I’d make is that if we were to respond to this competition by having lower corporate tax rates here, then it’s really important that it doesn’t come at the expense of higher budget deficits. And in the US… the official estimates at the moment are that for the next five or six years, the budget deficits are going to average almost 5 per cent of GDP [a year]… I think that’s very problematic, and if we were to go in the direction of having lower corporate tax rates, then I think it would be a big mistake to do that on the back of higher budget deficits…

However we finance [cuts to corporate tax rates], it can’t be by running bigger budget deficits. There could be some other changes to the tax system.

Here, the IMF and the Reserve Bank governor are on the same page. Yes, there is a case for cutting corporate tax rates to avoid losing out on foreign investment we would otherwise get. But it is crucial that the tax cuts are paid for, and not financed by running budget deficits. What the government is proposing are tax cuts that are not paid for, and would come out of what it claims to be future surpluses, based on rosy assumptions about future growth, particularly in wages.

The IMF has pointed to where the parties could find middle ground, if they wanted to. We could have company tax cuts that are paid for, and would not threaten our very fragile budget balance. Neither side is remotely interested in that, at least this side of the election.

In the end, as Peter Martin argued in yesterday’s Age, it’s a question of priorities. Both the IMF and the governor are at pains to point out that there are many other paths to increasing Australia’s potential growth rate.

The IMF report shows that on an international matrix of Australia’s economic strengths and weaknesses, our main weaknesses relative to our peers are in innovation, labour-market efficiency (matching the skills of the unemployed to those needed for the jobs on offer) and business sophistication. “Strengthening trend [productivity] growth through a stronger innovation system, labour force skills upgrades, and reduced gender imbalances is critical,” it concludes. “Related programs should be underpinned by longer-term strategies, and longer-dated resource commitments.”

Moreover, lifting growth is not the only first-order economic issue: defending growth is just as important. Former Reserve Bank governor Ian Macfarlane once said that the role of the bank was to work out where the biggest threats to economic growth could come from and try to counter them. The IMF report, like many others, highlights two serious threats: a potential hard landing in China (which it sees as a “medium” probability) and a potential slump in housing prices (to which it, somewhat unconvincingly, assigns a “low” probability).

In a separate chapter, the report argues that a hard landing in China would hurt Australia only temporarily, in fact, and in the longer term could help us. At first sight, that’s hard to believe: last year we sold China $110 billion of goods and services, 30 per cent of our entire exports and 6.3 per cent of our entire output. If China experiences a hard landing, much of that would disappear rapidly.

But in that event, the IMF argues, the Australian dollar would fall sharply relative to other currencies. That would make our exports more competitive globally, and the sales lost to China would be made up in other markets. It could well be right. Some analysts argue that, with China maintaining a de facto currency peg to the US dollar, the markets buy or sell the Australian dollar as a substitute yuan, rising and falling with China’s fortunes.

The IMF is far more concerned about the need for tax reform in relation to housing than about company tax rates. It is particularly keen to see the states abolish stamp duties on property transfer and increase land tax instead; but the only government to do so has been the Australian Capital Territory’s, which almost lost an election over it. It is offended by recent Commonwealth and state reforms to impose higher taxes on foreign property buyers. It argues that the exemption of the family home from the capital gains tax “may encourage ‘excess’ demand for housing, excess in the sense that families prefer more to less space.” It goes on:

On the investment side, the combination of high capital gains discount rates and unlimited negative gearing can encourage leveraged real estate investment in market upswings. While similar tax incentives are also present in other countries, they tend to be more limited… Housing tax reform would strengthen the effectiveness of the overall policy response.

It backs this up with a three-page comparison of Australia’s tax regime on housing with those of comparable countries, noting recent reforms in Britain, New Zealand and Hong Kong to reduce incentives for property investment. Of the other seven countries surveyed, five ban negative gearing outright, and only New Zealand treats investors as generously as we do.

While the IMF is generally positive about the future of the economy, and echoes the government’s line that real wage growth will return as the labour market tightens, this part of its analysis is of little value. It relies on old, selective data that makes you wonder what its team learnt by coming here.

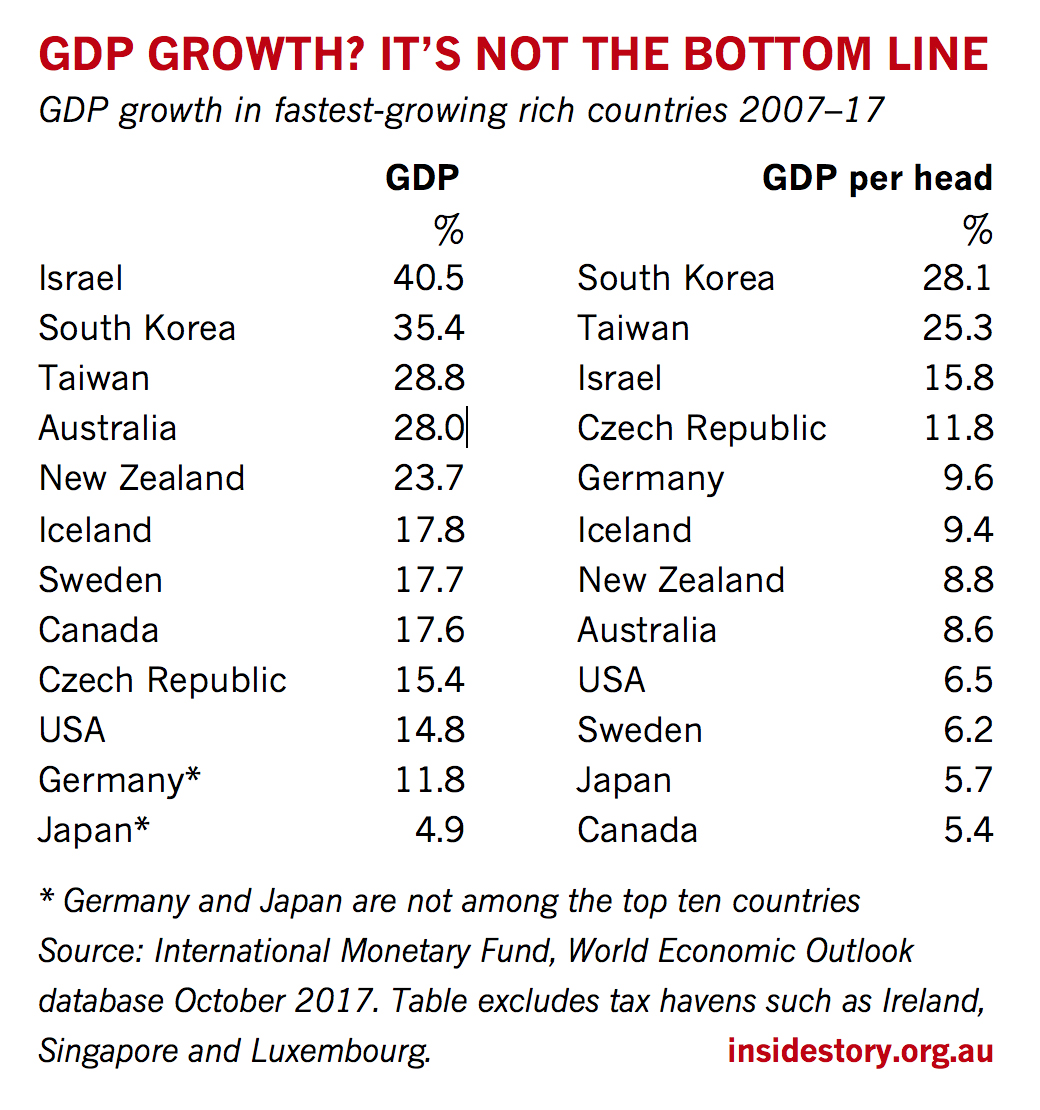

It declares that Australia’s recovery has been “robust,” and says “Australia has enjoyed high growth in per capita terms.” But Australia ranked only thirteenth out of twenty-seven comparable countries, even between 2010 and 2016. That’s the report’s only reference to per capita growth, which is, after all, the bottom line for economic performance. The IMF’s own data (see chart below) shows that while Australia’s GDP growth over the past decade has been among the highest in the Western world, it slips to eighth among comparable countries when you focus instead on the issue that matters: growth in GDP per head.

The IMF team seems not to have even noticed that, while Europe has rebounded vigorously, Australia has sunk to almost the bottom of the ladder. Within the twenty-eight-member European Union, its current per capita growth rate of 0.9 per cent would place it equal twenty-seventh with Britain. That’s not “robust” growth, my friends.

Similarly, it declares that unemployment in Australia “is relatively low,” giving as evidence the fact that it was lower than most other Western countries between 2010 and 2016, when Europe took a long time to recover its mojo. But by the end of 2017, Australia’s stagnant unemployment rate ranked only equal fourteenth of the twenty-seven countries on the IMF’s list. Were its experts not even aware of that? Or that Australia’s underemployment rate is just about the highest in the Western world?

One last thing that has escaped notice. In his testimony to the House committee on economics, Dr Lowe pointed out that a combination of low wage growth and strong growth in employment is not unique to Australia. It is happening throughout the Western world, as companies and workers fear losing their competitiveness. It’s a very good point, which we’ll come back to in another article. ●