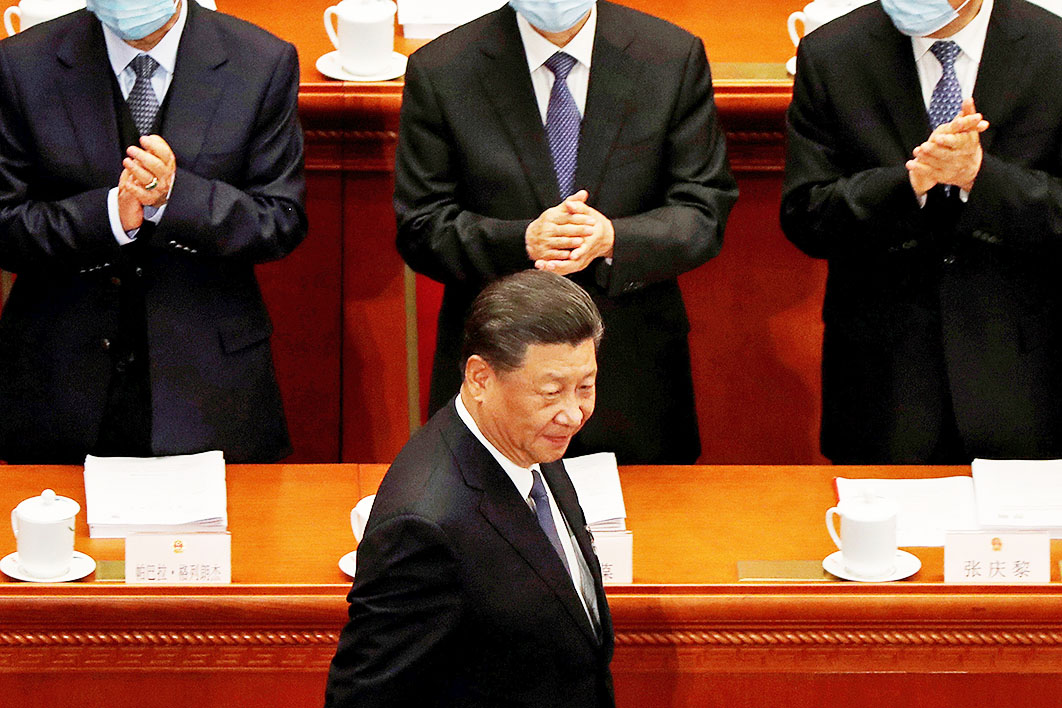

Xi Jinping is standing in an open military vehicle as it rolls down Beijing’s Avenue of Heavenly Peace. He greets the thousands of troops lined up on either side: “Comrades, thank you for your work!” Heads swivelling to keep their gaze on him, the soldiers shout back, “And you for your work!”

That was October 2019, and the Chinese Communist Party was celebrating the fact that its republic not only had survived for seventy years but was also thriving, long after the Soviet pioneer of the Marxist-Leninist state had dissolved. Earlier that day, Xi stood on the balcony overlooking Tiananmen Square from which Mao Zedong famously declared in 1949, “The Chinese people have stood up.” Recalling those words, Xi added, “No force can stop the Chinese people and the Chinese nation from forging ahead.”

In the months since then, and especially since the coronavirus’s emergence in Wuhan, Beijing has confronted many challenges — and reacted to each of them with unabashed force. It imposed a new national security law on supposedly autonomous Hong Kong. It sent troops to a contested part of the Himalayan border, where they engaged in a deadly brawl with Indian soldiers. It dropped the word “peaceful” from its reference to reunification with Taiwan. It sank a Vietnamese fishing boat in the South China Sea while its navy was mounting large-scale exercises. It stopped imports of Australian barley and beef in response to implied criticism of the Wuhan outbreak. Meanwhile, Chinese fishing boats continued to swarm around the Japanese-held Senkaku islands in a “grey zone” assertion of ownership.

As American and Australian political leaders and intelligence chiefs have signalled, China is also ceaselessly breaching Western cyber networks, and its diplomats and front groups continue their covert influence operations. The US Federal Bureau of Investigation says it has 2000 cases of suspected Chinese espionage on its hands, and Washington has closed down Beijing’s consulate in Houston, calling it “a hub of spying and intellectual property theft.”

Even among authoritarian regimes, China’s roll call of provocative activity is breathtaking. But judging what it all adds up to is far from straightforward. Is China demonstrating its strength, and reminding the West of its resolve never again to bow down? Or is it flailing around, picking fights it can’t hope to win?

“Just about everything in that set can be interpreted either as a sign of weakness or a sign of strength,” observes China historian Richard Rigby, a former consul-general in Shanghai who went on to be top China watcher at Australia’s Office of National Assessments. For Jane Golley, director of ANU’s China in the World Centre, it’s “the million-dollar question.”

American president Donald Trump and his secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, have taken a bet that it’s weakness. In his extraordinary speech at the Richard Nixon memorial library in California on 23 July, Pompeo walked away from the China policy that Nixon initiated in 1971–72. America had to admit a “hard truth,” Pompeo said. “If we want to have a free twenty-first century, and not the Chinese century of which Xi Jinping dreams, the old paradigm of blind engagement with China simply won’t get it done. We must not continue it and we must not return to it.”

The expectation that China would become more open, free and friendly has not been borne out, he said. America had “opened its arms” to China and “marginalised our friends in Taiwan” only to have China steal intellectual property, take millions of American jobs and demand silence on its human rights abuses. “President Nixon once said he feared he had created a ‘Frankenstein’ by opening the world to the Chinese Communist Party,” Pompeo said, “and here we are.”

After listing the Trump administration’s recent moves against China — banning semiconductor supplies to communications giant Huawei, sanctioning officials over the mass brainwashing of the Uighur minority, arresting Chinese students for espionage, declaring certain Chinese maritime claims legally invalid, closing the Houston consulate — Pompeo went on to declare a goal of regime change.

“We must also engage and empower the Chinese people — a dynamic, freedom-loving people who are completely distinct from the Chinese Communist Party,” he said, singling out in his audience two veteran exiles of crushed Chinese democracy protest, Wei Jingsheng and Wang Dan. “Communists almost always lie,” Pompeo said. “The biggest lie that they tell is to think that they speak for 1.4 billion people who are surveilled, oppressed, and scared to speak out.”

But people were waking up to this “from Brussels, to Sydney, to Hanoi,” he said. So now he was calling on “every leader of every nation to start by doing what America has done — to simply insist on reciprocity, to insist on transparency and accountability from the Chinese Communist Party.”

The ally most eagerly responding to this call has been Scott Morrison’s Australia. It had already barred Huawei from its future 5G mobile networks. Within days of the American declaration on the South China Sea, it issued a statement saying it too rejected many of China’s claims there, including the expansive “nine-dash line” delineating its claims of historical sovereignty over most of the sea. Five of the Australian navy’s most powerful ships were revealed to be engaged in exercises with US and Japanese ships off the Philippines.

Within a week of Pompeo’s speech, foreign minister Marise Payne and defence minister Linda Reynolds had flown to Washington for talks with Pompeo and US defense secretary Mark Esper. It was a pointed gesture of support, given that this routine annual consultation could have been handled by secure teleconferencing like most intergovernmental talks during the pandemic, and it meant that both ministers, their departmental heads and accompanying staff will have to quarantine for two weeks on return.

Australia duly got praise from Pompeo for “standing up” to China. But at what cost? It risked looking like support for Donald Trump less than a hundred days out from an election that polls say he will lose. And if China-blaming were going to be Trump’s election theme, to divert attention from Covid-19 disarray and unemployment, on whom would China take it out? And who could guarantee that Trump would not suddenly announce another “amazing” trade deal with Xi to settle it all?

The ANU’s Jane Golley, an expert on the Chinese economy, says we’ve just seen an example of that risk. “If you look at how the Chinese have played the barley story out here in Australia, they’ve been pretty clever,” she says. “Pushing forward a problem that they’d had with us in the past, but doing it to satisfy the demands of the US that they buy more exports from them. Then they cleverly turn around and target us, America’s number one ally, who keeps standing up and making all the noises, most obviously the Covid inquiry, that the US wants us to make. And then we turn around and say, ‘Isn’t China awful,’ and somehow the US gets away almost entirely scot-free.”

In the event, Payne and Reynolds declined to go “all the way” with Pompeo, saying Australia would reserve its decision on challenging China’s South China Sea claims by naval sail-throughs, and look to Australia’s national interests.

In China itself, Pompeo’s appeal to the Chinese people might actually increase popular support for the party leadership, according to an array of China experts. Daniel Russel, a China specialist who was assistant secretary of state for East Asia and Pacific affairs under Barack Obama, calls it “primitive and ineffective.” In fact, a recent report from the Ash Center at Harvard University, Understanding CCP Resilience, reported that surveys of Chinese public opinion between 2003 and 2016 show citizen satisfaction with government to have steadily increased. “Chinese citizens rate the government as more capable and effective than ever before,” the authors say.

Since the post-Mao economic opening in 1978, per capita gross domestic product has grown sixtyfold, lifting 800 million people out of poverty but also intensifying inequality. Under the previous leadership of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao the government attempted to compensate by allocating more spending to rural and inland areas and extending health insurance coverage to 95 per cent of the population. One big cause of the remaining dissatisfaction is air pollution so bad that it causes a million premature deaths each year — suggesting this is an area where China and the West could put aside differences in future re-engagement.

The anti-corruption campaign launched by Xi Jinping, who took over at the end of 2012, further improved the government’s standing. Although Xi’s campaign had elements of a political purge, the public saw it as evidence that even powerful figures no longer enjoyed impunity.

It soon became evident that the anti-corruption campaign was part of a drive by Xi to centralise authority in himself. The campaign reached into the Politburo Standing Committee itself, ensnaring Zhou Yongkang, the minister in charge of state security and public security and thus a powerful potential rival. Control of economic and social sectors was brought under various “working groups” chaired by Xi himself, rather than premier Li Keqiang. As ex-officio chairman of the Central Military Commission, Xi launched a purge of officers running promotions rackets and other scams, then, having terrified everyone, started a wholesale reorganisation of the military to reduce the standing land army, boost the naval and air forces, and set up joint fighting commands instead of regional garrisons. Then, in July 2015, police arrested some 300 lawyers known for defending critics or victims of official abuses.

Xi overlaid it all with his China Dream, which envisaged a once-powerful nation restored to the respect of the world. In 2015, he revealed the Made in China 2025 blueprint for gaining leadership in cloud computing, quantum computing and a host of other new technologies.

Perhaps most revealingly, he declared in the run-up to the 2017 party congress that the distinction between government and party no longer mattered. At the congress itself, he declared that the party should be everywhere: “Government, military, society and schools, north, south, east and west — the party is the leader of all.”

And there was no doubt who was in charge of that party. The congress declined to follow the custom of nominating a new duo of heirs apparent, effectively abandoning the convention that presidents and premiers serve for two five-year terms and leaving it open for Xi to get himself a third term in 2022.

Australia’s ambassador in Beijing between 2007 and 2011, Geoff Raby, author of a forthcoming book on Australia’s place in the US–China contest, says that orderly succession had already been destroyed before Xi took power. Ahead of the 2012 congress, Bo Xilai, party secretary in Chongqing and son of a revolutionary general, tried to get himself onto the Politburo Standing Committee and thereby within leadership range with a very public campaign of “Red” patriotism. Helped by a scandal involving money and murder, Xi and his allies had Bo purged. But what was left in the party, Raby says, is “the law of the jungle,” and Xi “has had to wind up the authoritarian dial ever since.”

In his recent book, Xi Jinping: The Backlash, the Lowy Institute China specialist Richard McGregor portrays a leader who has made a heap of enemies with his purges and can’t get down from the tiger he has mounted. ANU’s Richard Rigby agrees that a secure retirement is not a prospect for Xi. “He hasn’t left himself an off-ramp.”

Although Xi is past the halfway mark of his second term, some educated Chinese are still bemused. “No one saw this guy coming,” one friend told Raby. “Who is he?”

Geoff Raby thinks that the key to Xi Jinping is his father. Xi believes that Xi Zhongxun should have run the early People’s Republic, not Mao, and that he would have done a better job of it. Despite the imprisonment and humiliation the father suffered, and the son’s disrupted education, it was time to correct history and restore the revolutionary bloodlines. “This whole generation of princelings claim that suffering as their legitimacy,” says Raby.

For all his modest personal demeanour, Xi has elevated himself to Mao-like standing. His writings, turgid and devoid of Mao’s poetic flashes, are promoted as comparable to those of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Mao. The party’s ninety-two million members are expected to read them religiously, and are quizzed regularly by a mobile phone app to make sure they are up with doctrines like the “Six Stabilities,” the “Six Securities,” the “Five Hopes” and, most basic of all, the “Two Upholds” (upholding the party’s total control, and upholding Xi’s control of the party).

At the beginning of July, just in case of any falling off in devotion, Xi signalled another anti-corruption purge, with the party’s central political and legal affairs commission, which supervises the police and the judiciary, announcing a new “education and rectification” campaign that would “thoroughly remove tumours… scraping poison off one’s bones.”

The only surprising thing is that a few intellectuals are still ready to be publicly critical. Among them is the Melbourne University–educated legal academic Xu Zhangrun, who published an essay in February attacking the regime’s handling of the Covid-19 crisis. Xu has been sacked from his position at Beijing’s elite Tsinghua University and stripped of all entitlements, but is so far at large. Even more surprising is that many individuals have come out in his support.

But there is little reason to think that the Chinese public’s satisfaction with the government has fallen since the last Ash Center survey in 2016. Hong Kong’s protests drew little sympathy on the mainland, especially when some activists vandalised public property. And China’s leaders have been models of grown-up maturity compared with Donald Trump and his rotating cast of acolytes.

“Particularly in the US, there’s a lot of wishful thinking, that the Chinese administration is weak, that the government is weak, on the brink,” says Jane Golley. “It is one of the biggest questions of our time: how sustainable is a one-party system that becomes increasingly authoritarian and suppresses individual freedoms? But the people seem to be still signalling that they are still happy with it — or satisfied, let’s say.”

If anything, says Golley, Covid-19 has reinforced that sentiment. “I haven’t seen any survey, but what I’ve heard anecdotally is that Chinese people are looking at the US and their own handling of Covid and saying what a wonderful job their government’s done.”

As another China watcher, William Overholt, also of the Harvard Kennedy School, pointed out in Inside Story earlier this year, the Covid-19 crisis has brought out all the contradictions — as Marxists might put it — in Xi’s handling of the Chinese economy: support for market allocation of resources alongside massive subsidies to state enterprises; attempts to stimulate household consumption while pump-priming the economy with yet more infrastructure and construction; unleashing private entrepreneurship but putting party commissars onto company boards.

For a decade, China’s economists and technocrats like Premier Li, the only Politburo Standing Committee member with an economics degree, have been urging a “rebalancing” away from exports and infrastructure to private consumption. But politics, in the form of government spending designed to prop up GDP growth, has always beaten economics.

This tendency has given rise to a new wave of what Golley calls “collapsist” arguments — the view that China is heading for a massive bursting of bubbles. Certainly there are plenty to be burst, including a recent bull run on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges and a new housing boom despite an estimated sixty-five million unoccupied apartments across the country. Domestic debt is 317 per cent of GDP, and some small banks have gone bust because of bad loans, but tight currency controls and the central role of government banks may postpone the reckoning indefinitely.

In fact China, along with Vietnam, will be one of the very few economies to show positive growth this year, though that’s assuming the massive mid-year Yangtze valley flooding doesn’t damage the recovery from the first-quarter Covid-19 shutdown.

“The economy has been the leadership’s primary source of legitimacy for forty years, and even with this Covid crumbling they’re still doing better than anyone else,” says Golley. This matters to Australia, too. “We’re talking about what’s looking more and more like an economic war already, you might define it as a cold war,” and we risk siding with a country “heading for minus 10 per cent GDP growth” against an economy “likely to grow between two and three per cent this year.”

Debt is obviously a challenge for China, says Golley, “but they’ve got fiscal tools, they’ve got a little bit of scope with monetary policy, they’re the masters of intervention, so they will find ways to be the most rapidly growing economy coming out of Covid. And that’s going to give the government and the party more resilience, and more satisfaction.”

For Australia, says Golley, it’s the loss of jobs that will hurt if China keeps retaliating. “I’ve met barley farmers on Twitter and scrambling around trying to figure out what to grow next. I think the economy is going to take such a huge hit, but this current government, they don’t care. It’s all the poor and unskilled who are going to end up out of work.”

The big question about China’s strength is sustainability. Annual growth may not get back to the 7 per cent that has long been regarded as necessary to keep up employment and income levels. Xi seems worried about the prospects for the latest crop of university graduates, and is even suggesting that spells of rural work should be part of education. But even 5 or 6 per cent growth would keep China powering ahead against the United States and other rivals.

Stricter foreign investment controls in the United States, Germany and elsewhere is making it harder for Xi’s Made in China 2025 project. The Huawei issue has morphed from a concern about national security vulnerability in 5G networks to an American attempt to keep China down. And the trade war is not about trade any more, according to Columbia University historian Adam Tooze: “what dominates the discussion at present isn’t soy beans or blue-collar industrial jobs, but microchips, cloud computing, 5G and intelligence gathering by way of TikTok. What is at stake is technological leadership and national security.”

In the event of the United States “decoupling,” as some security hawks seek, China is comparatively well placed to thrive on its own. With 1.4 billion people, the long-delayed rebalancing would create a massive internal market. “They would be much better off in a globally closed economy than we are,” Golley says. “We’d be one of the worst off. The Americans could handle it better than we can with their population.”

Which raises the question of how many Chinese there are, and how many there will be. One demographer, US-based Yi Fuxian, thinks the official 1.393 billion figure may be overstated by as many as 115 million people, thanks to efforts to cover up the impact of the brutally enforced one-child policy between 1980 and 2015. Even since it was lifted, couples are not having more babies, which means that China will see Japan-style population contraction within a few years.

The fall in population might even have started, writes US demographer Lyman Stone. By 2080, and perhaps even 2050, China’s military-age manpower advantage over the United States and its allies would vanish (though future wars are unlikely to be fought that way). On the economic side, China will have to sharply increase the education, skills and creativity of its shrinking population to keep expanding. It could be caught in a classic “middle-income trap” before the presently impoverished third of the population achieves middle incomes.

A nasty corollary of that projected decline is that people of the Han majority are being encouraged to go forth and multiply but the freedom to have large families previously allowed to the ethnic minorities is being wound back. Hence the stories coming out of Xinjiang that Uighur women are being sterilised or implanted with contraceptive devices against their will. “Under president Xi Jinping, long-standing efforts to Sinicise minority groups have been ramped up to an unprecedented scale,” writes Stone.

For the moment, Xi Jinping enjoys a strong domestic position. How, then, has this not translated into greater world influence?

China’s most supportive foreign friends — the main recipients of US$5.5 trillion in loans from Beijing, or about 6 per cent of global GDP — make up a list of weak, corrupt and/or authoritarian regimes. Neither Turkey nor Pakistan criticises the oppression of the Uighurs, for instance, nor do governments in much of the rest of the Muslim world. And now many of these client states are pleading hardship about repayments.

Beijing has had to work hard to defend its early lapses in handling the coronavirus. It has had to deal with the backlash after local people discriminated against the many African traders living in southern Guangdong earlier this year, which led to Nigeria’s parliament unanimously protesting against “maltreatment and institutional racial discrimination” against Nigerians resident in China. Although China is spending billions of dollars on protective equipment and other health measures around the world, the fifty million–strong worldwide ethnic Chinese diaspora is experiencing a rise in racial vilification because of Covid-19, including in Australia.

But the United States in pandemic freefall is hardly a model for the world. How could China not be reaping the benefit globally? To the contrary, according to surveys by the respected Pew Research Center, trust in China has been falling in a swathe of advanced economies during Xi’s second term. It is unlikely to have suddenly rebounded.

“I find China’s behaviour inexplicable,” says former Australian trade representative in Beijing and Shanghai Michael Clifton, chief executive of the China Matters “second track” forum in Sydney. “The thought that they should be losing the global battle for hearts and minds in the era of Donald Trump is just beyond me.”

Beijing seems to lose its cool whenever events threaten its two core interests: territorial integrity and absolute party rule. At least four of the recent flare-ups relate to the first, and Hong Kong to both. In turn, the crackdown in Hong Kong led to deepened distrust in Taiwan, and a boost in support for president Tsai Ing-wen of the independence-leaning Democratic Progress Party. Japan, its Senkaku territory and perhaps in future the Okinawan island chain subject to Chinese claims, has deepened its military engagement with the United States, Australia, Vietnam and India.

The border clash with India is still murky. International relations and territorial dispute expert M. Taylor Fravel thinks it might have started with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s decision last August to withdraw strife-torn Kashmir’s statehood and run its high-altitude Tibetan-populated region, Ladakh, as a “union territory” directly from New Delhi. Modi’s home minister, Amit Shah, followed this up by strongly reasserting India’s territorial claims and publishing a new map.

When China moved troops to the disputed area, Aksai Chin, India did likewise. Though China had created the conditions for the clash that followed, it had not been intent on one. “I don’t think the clash is something that China sought,” Fravel told the Print newspaper. “Because if one looks at Chinese diplomacy today, they are very much clearly trying to put the genie back in the bottle, restore China–India relations to a place they were before the clash. China hasn’t released its own casualty numbers, and so forth.”

It hasn’t worked so far. Modi has banned TikTok, among more than one hundred popular Chinese mobile phone apps, and welcomed a new factory in Chennai that would take manufacturing work on Apple’s iPhone 11 away from China. He is also moving to strengthen the “Quad” military alignment with the United States, Japan and Australia.

And while Trump has put the United States in a disgraceful position, China has clearly been taken aback by his wielding of non-military power: in getting Canada to detain the Huawei executive and heiress Meng Wanzhou for possible extradition; in placing sanctions on Xinjiang officials that could see Chinese banks blocked from international clearing systems if they don’t join in; in suddenly embargoing the semiconductors Huawei needs.

While Beijing officials have been cleared to make tough responses to challenges from countries like Britain and Australia, they take a cautious and regretful line with Washington. The closure of the US consulate general in Chengdu, in response to Houston, was a measured tit for tat, not an upping of the ante. Demonstrations by “patriotic citizens” were allowed as American diplomats moved out, but Chengdu residents were also allowed to post friendly social media farewells to the American consul and his wife and even put up clips of wartime newsreels from when the US military operated out of nearby Chongqing supporting China against Japan.

Nevertheless, it looks like being a fraught hundred days until the US elections are over. Trump is painting his contender Joe Biden as a sellout to the Chinese; Chinese propaganda officials are saying they want Trump to win because he will bring down America and destroy its alliances. It all means that under Trump or Biden, engaged or decoupling, Washington will have permanently firmed up against China.

As for Xi Jinping’s position, it will continue to be enigmatic. “Any shock will come in elite politics,” said Geoff Raby. “It will be played out in a way we can’t see, that we won’t know about until it’s happened.” •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.