The Victorian Liberals have been in what my mother would call “the wars” in recent years. First, they were booted from Spring Street after just one term in office — something that had not occurred in the Garden State for half a century. Then it was discovered that the party’s state director, Damien Mantach, had been defrauding the party of much-needed campaign dollars during 2014 — 1.55 million of them, in fact. More recently, state leader Matthew Guy — who is in striking distance of the premiership this November — managed to get caught lunching with an alleged organised-crime figure, Tony Madafferi, a revelation that hit the media just as an advertising blitz put Guy’s face on posters right across Melbourne. Now, an internal stoush over a party-linked investment fund, the Cormack Foundation, threatens to spill into open court.

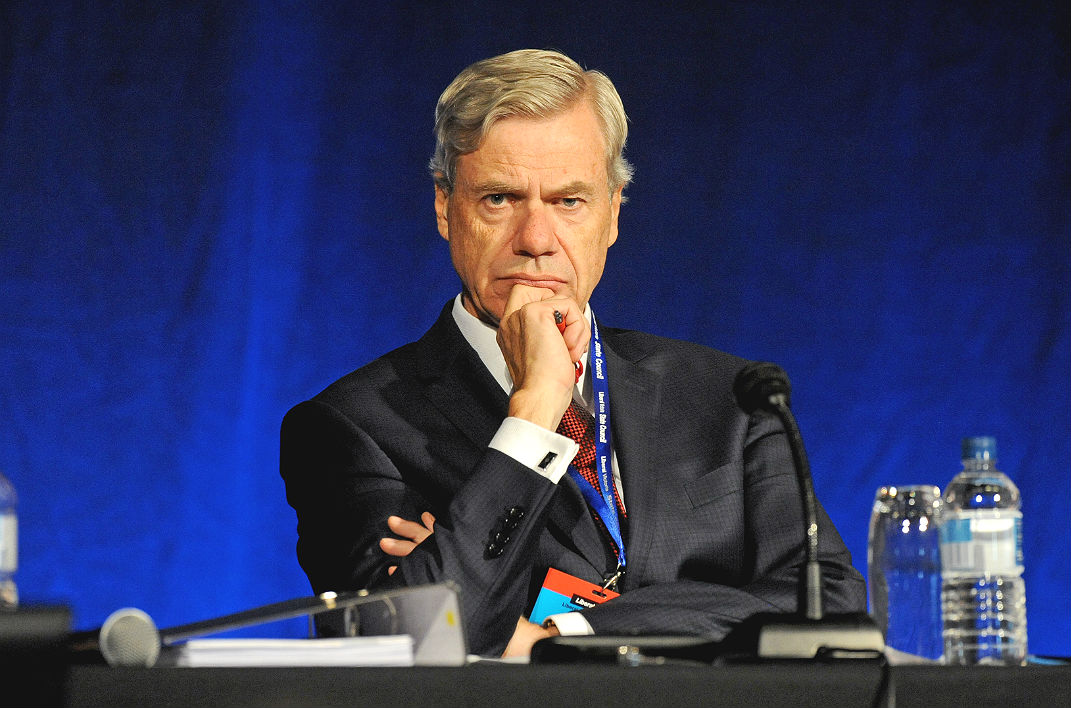

Cormack, a key source of funding for the Victorian Liberals, hands over more than a million dollars to the party every year. At least, it did until last winter, when its board decided to turn the tap off. The party, and particularly state president Michael Kroger, is fuming, asserting the foundation is supposed to be managing funds for the Liberals. The board disagrees, declaring itself entirely independent. Both sides have lawyered up and are preparing for a fight to the death in the full glare of the press, nine months out from a state election. Like I said — the wars.

This is not just a run of bad luck for Victoria’s Liberals. It is part of a larger upheaval. For decades now, the state division has been undergoing a slow, painful metamorphosis from a pragmatic, almost centrist Establishment party, to an angrier, more ideological outfit for conservative outsiders. You could say they are slowly but surely losing their genteel civility and going feral.

That’s ”feral” not in any pejorative sense, but strictly in zoological terms. Where once the Victorian Liberals were thoroughly domesticated and moderated by their long residence in the halls of power, they are now part-way through a decades-long process of shedding their pragmatism, their trust in existing institutions and their ideological flexibility. Having spent years in the political wilderness, they are returning to baser instincts and harsher attitudes.

And it has been many, many years now. The Victorian Liberals have held government for just four of the past nineteen years. Federally, Victoria has become a reliable Labor state: Liberals have done poorly, even when they are being swept to power by the rest of the country. Sydneysiders have dominated the party leadership in Canberra for decades. It’s a long time since Victoria was the jewel in the Liberal crown, as it was during the long reigns of Bob Menzies in Canberra and Henry Bolte in Spring Street.

Indeed, it can be difficult to appreciate just how dominant and influential the Liberals were in the now-progressive Garden State. They completely remade Victoria’s politics in the postwar era, founding what could nearly be called a new political order.

Before the Liberal Party arrived on the scene, the state’s politics were notoriously chaotic. Conservatives, reformist liberals and, later, Labor forces were fairly evenly split in the parliament. Alliances were constantly drawn and redrawn; parties were desperately undisciplined; splits and fusions transformed the political landscape with dizzying frequency. If nothing else, the tumult kept the Victorian governor busy. In 1861 alone, the colonial governor, Sir Henry Barkly, found himself offering nine commissions of government, with nobody willing to take the poisoned chalice. Government changed hands almost annually.

That chronic instability came to an end with the rise of the Liberal Party in Victoria. Governments began lasting much longer, for one thing. From Federation up to the election of Henry Bolte in 1955, the average Victorian premier lasted 1.8 years. From Bolte onward, that figure blew out to 5.9 years. Bolte himself was the state’s longest-serving premier, lasting seventeen years; his successor, Dick Hamer, got eight years in the chair. This was something Victoria had never seen before — one party governing, continuously, decade after decade — and the Liberals became synonymous with power.

The stability and discipline of the Liberals changed the whole character of the political contest in Victoria. The old three-cornered free-for-all settled into a more structured, bipolar contest we might more readily recognise today. Parliamentary dominance also allowed for power to be concentrated in the executive, away from the legislature and the state’s many and massive statutory authorities. Decades later than other states, Victoria had finally made the transition to a “party” — as opposed to a “parliamentary” — system of government. And the dominant party in that system, for its first three decades at least, was the Liberal Party.

No longer. Now, the Liberals are more habituated to the wilderness than the halls of power. And those long stints on the outside have made their mark on the character and politics of the party. Their first taste of long-term opposition — the ten years of John Cain and Joan Kirner’s Labor governments — saw the party take a decisive turn under the leadership of Jeff Kennett. Kennett’s temperament was aggressive and irreverent, at times shocking his colleagues and Establishment elders. His brutal and unforgiving tactics included attempts to block supply or revoke parliamentary pensions to force an election.

In government, Kennett put a wrecking ball through time-honoured institutions and traditions, many carefully established and nurtured under his Liberal predecessors. He was, in that sense, more revolutionary than conservative, more radical than pragmatic. It would be wrong to say the Liberals had gone completely feral at this stage — the Melbourne Establishment remained fairly well embedded in the party and the government — but these wild flashes, this irreverence, this streak of revolutionary zeal, betrayed a new distrust of conventions and institutions.

Perhaps the thing holding back a fuller expression of that feral turn was the presumption that the Liberals were back to stay. To the surprise of many, they managed only seven years in power before being dispatched by the electorate. And this time around the business and civic Establishment of Melbourne began to decouple itself from the Liberals. Slowly but surely, it began to cosy up to the very business-friendly, third-way, New Labour–style governments of Steve Bracks and John Brumby. Business figures and corporations, lobbyists and elite civic groups all began to reorient themselves, hiring Labor-friendly lobbyists and board members, donating money, attending events and joining supporter groups.

We need only look across the Murray to see what kind of party the Victorian Liberals were morphing into. Political historian Norman Abjorensen has written that the New South Welsh Liberals always had an “intensely tribal ‘outgroup’ mentality.” Stuck in a natural Labor state, they existed on the margins of power, with Labor dominating nearly all institutions — from parliament and the bureaucracy to local government, schools, the professions, the judiciary, and even many churches and sporting clubs.

Perhaps forgivably, the NSW Liberals had adopted a kind of siege mentality. They were insular, suspicious and more uncompromisingly ideological. This is not to say there were no moderates in New South Wales, any more than there had been no hardliners in Victoria. But the basic cultural difference between the states had been fairly stark: New South Wales had the outsider’s chip on the shoulder, was deeply suspicious of the Establishment and was more aggressively right-wing; the Victorians were the Establishment, more pragmatic, more flexible, sometimes positively progressive in their liberalism. Now, no longer the Establishment, the Victorians began to resemble their tribal cousins to the north.

This shift was on show during Ted Baillieu’s tortured leadership of the state party. Baillieu himself was an Establishment scion, a member of one of the oldest elite families in the state. He was noted for his moderation, his pragmatism, and his relaxed, unflustered style. All this was in keeping with the old Liberal Party. But by the time he was at the top, the party had changed, and he struggled to wrangle the feral elements that had emerged. In opposition, he suffered constant leaks and backgrounding by disgruntled factional enemies. Some members of the party’s state office even set up a website decrying “Red Ted” and his moderate politics. Tony Nutt — ex–John Howard consiglieri and all-purpose party fixer — had to be brought in to hunt down and purge the rebels. Leakers in the party room and the shadow cabinet similarly had to be rooted out and sacked every six months or so — year after year.

All this was feasted on by the state media, something Baillieu never seemed to forgive; he was guarded, often openly hostile in front of journalists, speaking rarely and briefly. Nor could he forgive the party’s natural allies — the chamber of commerce, banks, financiers, the freight industry — for cosying up to and even openly backing Labor.

Baillieu carried all these wounds and suspicions over into power. Reading the party’s own autopsy on the Baillieu years, we see how the premier’s office — distrustful of Baillieu’s colleagues, indeed distrustful of the whole world outside his office — micromanaged the government. Most serious decisions were taken away from cabinet and given to subcommittees where fewer enemies lurked. Journalists were starved of information, and what little they got was delivered through gritted teeth. Interest groups found it impossible to get access to the government; stakeholders were thrown off-side by policy surprises, or felt nobody in government was listening.

And so, despite leading his party out of the electoral wilderness and despite winning with a sizeable swing and a double majority, Ted Baillieu found himself struggling with backbiting and white-anting within months of taking office. Abortion, the Human Rights Charter, department secretaries kept on from the Labor years, the lack of big infrastructure projects, the lack of boldness, zeal and aggression — all were the subject of intense infighting. By Christmas 2012, the premier was hanging by a thread. The following March, when Frankston MP Geoff Shaw quit the Liberals over an investigation into his misuse of entitlements, Baillieu lost his majority in the Assembly. He resigned, swiftly, before his enemies could get in first. All this just two-and-a-half years into a new government. This is what a feral party looks like.

Now, in opposition yet again, the Victorian Liberals are just about in meltdown. On paper, the party should be within reach of government later this year. But it is desperately low on cash, at war with its main funder, and engaged in internecine internal warfare, the ferals outmanoeuvring and, according to some, out-stacking the Establishment all over the place. If there were grumblings and whispers coming from these elements during the Baillieu years, there is now a full-blown insurgency — almost the kind of thing we saw the Tea Party engineer in the United States before Donald Trump came on the scene.

None of this means that the Liberals won’t win back power in Victoria in November, or that they won’t manage some good results federally. An angrier, more right-wing, more feral party might even manage to speak to the disillusioned, non-major-party-voting chunk of the electorate that can make the difference in Australian elections these days. But it almost certainly won’t resemble the golden postwar era of stability. More likely than a feral-right hegemony in Victoria is a return to the old days of factiousness, division and instability. And it is not just the Liberal Party unravelling — both major parties are struggling with their response to a flagging primary vote.

That is the context for the Cormack stoush, due to come to court in Melbourne next month. Indeed, it is the crisis facing the Liberals in microcosm: the Cormack board is constituted by old-guard Liberals with eminent Establishment credentials; rather suddenly, they have found themselves wavering in their commitment to the party, at least under its current leadership, with Michael Kroger at the helm. On the other side is Kroger, who, despite being the consummate party insider, is fashioning himself more and more as an anti-Establishment crusader, lambasting the Business Council of Australia, expelling all MP staffers from the state’s administrative committee, and acting as patron of hard-right up-and-comers who are recruiting whole churches out in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs.

The stoush is between two Liberal parties — old and new, domesticated and feral. Perhaps the two can find some accommodation and divert the conflict from the embarrassment of open court next month. Perhaps not. Either way, this is not the beginning, nor is it the end of the upheaval for Victoria’s Liberals. ●

• James Murphy’s analysis of Justice Beach’s decision in the Cormack Foundation case.