In May’s federal election, for the first time ever, a majority of votes were cast early. A bare majority, it’s true: to the nearest half integer, the percentage very likely rounds to 50.5 per cent.

A record 33 per cent were “pre-poll ordinary” votes. This option, available since 2010, essentially replicates the election-day experience but can happen anytime during the two weeks before. (For the 2016 and 2019 elections the period was three weeks.) Another 4 per cent voted early, in person, by “declaration,” meaning their ballot was submitted inside an envelope with a signed form (usually because their name couldn’t be found on that portion of the roll).

And a record 14 per cent voted through the mail — an almost doubling of 2019’s 8 per cent, which was a drop from the previous election. This year’s figure was, of course, a result of the pandemic. And like many Covid-induced behavioural changes, the extent of any snapback to previous modes of behaviour remains to be seen.

What does the electoral class — experts, parliamentarians and others interested in the running of elections — think about these evolving voting methods? Should we all relax and go with the flow, or would it be better to insist that as many people as possible turn up on election day to immerse themselves in its binding rituals?

The answer so far has been to accommodate demands for convenience gradually, repeatedly drawing a line before yielding a little more several years later.

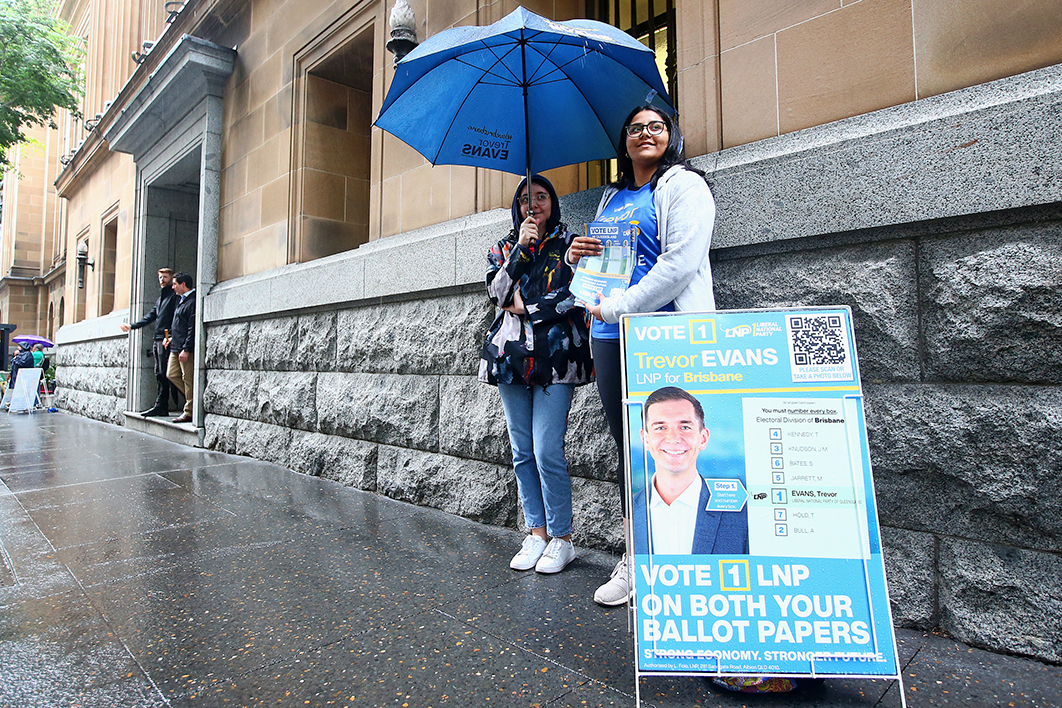

In the medium term, the explosion has been most obvious in pre-polls. Eighteen years ago, pre- and postal voting each accounted for around 5 per cent of turnout. As figures quoted above show, even in 2022 pre-polls were more than double postals. That’s due to the 2010 changes, and a commission that publicises pre-polling’s availability almost to the point of encouragement. Postal voting, on the other hand, is treated more like a necessary evil. (See, for example, electoral commissioner Tom Rogers explaining to a parliamentary committee just before the 2022 campaign why the commission prefers pre-poll.)

And yet, according to the electoral law, if you meet a criterion for one you meet it for the other; indeed, criteria for both are stated in the same schedule. Postal voters must sign a form or tick an online box declaring they meet one of those conditions. The pre-poller verbally affirms it to an electoral official. (The long schedule of reasons obviously isn’t read out; instead there’s a conversation along the lines of “Do you qualify to vote pre-poll?” “Yes.”)

What’s wrong with postal voting? To most election watchers its greatest sin is that it can hold up the election result because postal votes are not counted until the following week. (It really needn’t be like this; the Brits manage to count theirs on election night. If we really tried we could include most of them in the Saturday evening tally.)

A random voter, if asked, might offer that postal voting is more vulnerable to abuse. Letterboxes can be stolen from and postal workers might be tempted to interfere. Anecdotes — or sometimes versions of the same anecdote — abound of postal voting applications going unanswered. (It certainly happens, as two people I know found out in May.)

Perhaps people worry about postal delivery times. Letters take much longer to deliver than they used to, potentially missing the cut-off two weeks after polling day.

But there’s another problem. It doesn’t tend to worry the average voter, but it does concern many in the electoral law class: postal votes are not truly secret.

Why do we have the secret ballot? In Australia and other “advanced democracies” we tend to see it as a “right” — and so, by implication, an add-on. But secrecy was actually an integral part of the “Australian ballot” right from the beginning. It had to be, because if people were bribing or threatening others to vote a certain way (including at polling places), opt-in secrecy alone wouldn’t eradicate it. The state had to ensure a person had no way of proving to another how they had voted.

And postal voting isn’t compulsorily secret. Voters could be filling out their ballots in the visual presence of family, friends or anyone else. That was why voting by post came so long after the move to the Australian ballot in the 1850s. If postal voting had been available in the nineteenth century, bosses could instruct their employees, and landlords their tenants, to (a) apply for a postal vote and (b) fill it out the desired way, show it to them and let them to put in the mail. It was obviously a tractor-sized loophole.

In democratic countries with less-developed economies, such as our close neighbours East Timor, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, postal voting is either non-existent or limited to tiny classes of people — for example armed forces overseas — for this very reason. (In the case of East Timor at least, the absence of a postal system is an overriding factor.)

In Australia, though, anyone can vote postal as long as they sign the form claiming they qualify. Does this loose arrangement matter? The logistics, expense and likelihood of getting caught render the risk of this potential absence of privacy tiny, but we might still envisage, for example, one spouse (most likely the husband) instructing and supervising the other. Nursing home staff voting on behalf of residents is a possibility. Maybe the question is whether it would happen enough to worry about.

Earlier this year, as a Covid measure for a set of by-elections, the NSW electoral commission skipped the application process and sent postal votes to everyone on the roll. Voters could use them, or they could cast their vote in person. A touch under half of the turnout, 49 per cent, was postal.

In Switzerland they do this as a matter of course for national elections, and about 90 per cent of voters mail their ballots back. Estonia has for many years made internet voting available to all, and around a third of the electorate uses it. Some Australian local council elections are postal only. Is our third tier of government so unimportant that enforced secrecy doesn’t matter?

This, then, is a question for the future of voting at national and state elections: should remain hung up about secrecy?

There’s one other complicating factor: how private is in-person voting anyway? The Electoral Act says votes must be cast privately, but no penalties seem to apply for breaches. Australia’s booth layout sits at the more relaxed end of international practice. It’s easy to peek at your neighbour, especially if they’re willing to show you. (A couple of visual examples.) Few eyelids are batted. Electoral officials would probably intervene in egregious examples — but it would be too late in most cases.

And if I filled in my ballot and then, on the way to the ballot box, shouted out who I was voting for and held it up, I would likely receive a stern admonition but little else. Even if the official reached me before I got to the box, would they throw my ballot away?

Contrast this with rules during the counting of votes: if you put your name, or anyone’s name, on the ballot it is rendered informal because it supposedly breaches secrecy. (This rule really is an unneeded remnant of a bygone era, if for no other reason than that officials really have no way of knowing who wrote the name.)

Let’s step back and imagine elections were just invented and we were setting up an apparatus to conduct them. What might the arrangements look like?

We would create and maintain the electoral roll largely as we do now. A decade ago, with direct enrolment, Australia embraced modernity, using various government agency databases to do most of the work, complemented by elector-initiated activity.

And voting itself? Would it really be in person, on a single day? Or would it mostly be via the internet, including by email — security, and perceptions of security, allowing? A lot more work would be needed; NSW’s Ivote, which has been wound back to its original use by vision-impaired voters, provides a cautionary tale.

People who can’t access the internet would need some form of postal voting. And voting in person? In a big country like Australia, the fewer people who vote on election day the less easy it is to justify having six or seven thousand polling places scattered across the continent. (Switzerland, mentioned earlier, has a population density around sixty-six times Australia’s.) But decreasing the availability of Saturday voting would further encourage other voting channels.

The most recent ACT election, conducted during the pandemic, was framed by that jurisdiction’s electoral commission as a five-week “election period.” This might provide a partial template.

The early forms of “postal voting” in this country, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, actually involved people visiting their post office and doing the deed there, in front of the postmaster (but without he or she seeing how they voted!). The postmaster then posted an envelope containing the ballot to the returning officer. Gradually the class of people who could take votes in this way was widened. (Federally, it wasn’t until 1918 that electors began posting their own ballots.)

The mid-twenty-first-century version might see people voting at various government agency offices during the voting period.

And would something like MyGov have a place? In terms of perceptions of integrity, something might be said for people possessing evidence of how they voted. But see notes on secrecy, above.

Around the globe all manner of vote-taking can be observed. In America alone, the 3000-odd counties provide a rich tapestry, not just for their own but also for state and national elections. Some of that international experience is worth considering.

My crystal ball is no less murky than the next person’s, but change is already happening thanks to evolving social expectations and the contradictions inherent in current laws governing convenience voting: yes it’s allowed, but floodgate’s hinges remain intact by making people claim to have a good reason, even if it’s with a wink and a nod.

And much of the change will depend on decisions, explicit or otherwise, about mandated secrecy. •