When I first got an iPod, I shunned the shuffle function. It seemed to me the very opposite of active listening: a dentist’s waiting room, albeit with louder music selected by the patient. But I have changed my mind.

I forget, now, what eventually led me to try the random approach – perhaps it was simply that it was there – but I quickly became tantalised by it. I realised that I was listening more actively, not less; that every time a new track began, the first sounds came as a complete surprise, demanding my attention. Sometimes, because one tends to load complete albums on which not all the tracks are familiar, I was actually forced to attempt to identify the music, which requires very active listening indeed. I could have looked at the iPod to check the title, of course, but if you’re striding along the road, you don’t want to break your step; and anyway, this was fun!

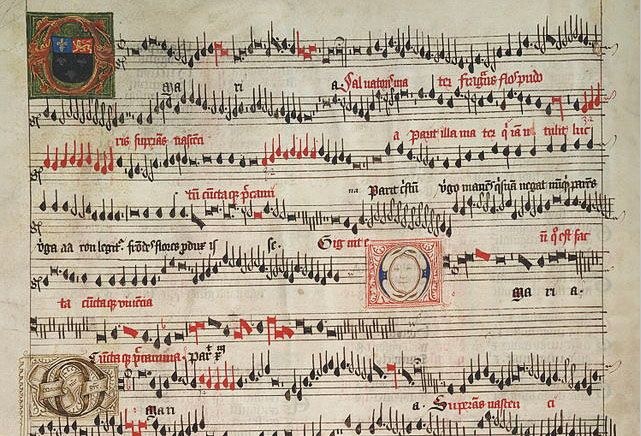

Over the course of half an hour, a song from an early Joni Mitchell album might give way to a movement from a Dvořák symphony, followed by something from the Eton Choirbook, a recent pop hit and then the arresting sound of Sandy Evans’s tenor sax. Even though I had selected all the music in the first place, because the shuffle function was genuinely random, the element of surprise was equally genuine. And it often led to a reconsideration of the music itself, or a first consideration when I found I couldn’t name what I was listening to. Sometimes, it prompted research on my part as I went off to learn more about this music that had, without warning, captivated me.

I enjoy serendipity. Some of the best learning happens this way. You are in a library or a bookshop and you spot an attractive yellow spine on the shelf. At the very least, you probably check the title; perhaps you take the book down and skim it; perhaps you take it home to read; you summarise it for a friend. I suppose, in a small minority of cases, you end up writing a doctoral thesis on the topic.

This is pretty much how good radio works, too. You turn it on and hear a piece of music you recognise but were not expecting, and you find you are listening harder. Or you hear something you don’t recognise at all, and listen harder still. It might be only for a moment – perhaps it doesn’t appeal or you aren’t in the mood – but maybe it grabs you and you keep listening till the end; after all, you will want to know what it is you’ve been hearing. The announcer tells you and now you want to hear it again, or you want to hear something else by the same singer or composer.

Over the years, interviewing musicians on The Music Show, I have often asked questions about what got them started. Time and again, the answer from Australian musicians – especially jazz and classical musicians, composers and experimenters – has been an early engagement with ABC radio; with pop musicians, perhaps, it’s Countdown or Rage.

This was certainly my own experience, though in my case it was the BBC. I had a small cassette player and would record things off the radio – at first pop songs, later contemporary classical pieces – that I thought I might want to hear again. It was all pretty random. Mostly I didn’t keep what I’d recorded and taped over it, but sometimes I nearly wore out a recording from repeated listening. One such was from a concert of Pierre Boulez conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra in Harrison Birtwistle’s The Triumph of Time. Even before I wore the tape out, the original quality of the recording must have been pretty dreadful – my technique involved holding the microphone next to a transistor radio – but it is no exaggeration to say that it changed my life.

I’d have been about fifteen at the time. In coming to know – and indeed love – this music, I also came to trust Boulez as a conductor and Birtwistle as a composer. Trust is the word, I think. As one might look for other books by an author one has enjoyed, I kept an ear out for other music performed by this conductor or written by that composer. When the music didn’t appeal to me instantly, I persevered because of the trust. Not all music reveals its qualities at once. In the end I was seldom disappointed. And, as always, one thing leads to another. In my case, one of the things The Triumph of Time led to was my becoming a composer, and a certain sort of composer at that.

Perhaps, reading the above, some reader has already typed “Eton Choirbook” into a search engine, or perhaps “Sandy Evans” or “Birtwistle.” Who knows where this might lead? •