Last week’s National Housing Conference kicked off in Sydney with a keynote presentation about Canada’s new housing strategy. Audible expressions of envy could be heard among the 1000-plus delegates when they were told that prime minister Justin Trudeau had launched the strategy (on national housing day) by declaring that “housing rights are human rights” and promising to enshrine the right to adequate housing in Canadian law.

Those fine words are backed by C$15.9 billion of federal money. Evan Siddall, president and CEO of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, told the conference that contributions from provincial and local governments could bring the total investment to around C$40 billion over ten years, sufficient to repair 300,000 existing dwellings and build 100,000 new ones.

Ottawa is spending C$4.8 billion to increase the quality and supply of public and social housing provided by provincial governments and community organisations, and putting another C$11.1 billion into a National Housing Co-Investment Fund offering low-interest loans to build affordable housing for the private rental market.

To get finance from the fund, 30 per cent of dwellings in a project must be rented out for less than 80 per cent of median market rates for a minimum of twenty years. That’s double the duration required under the successful but short-lived Australian equivalent, the National Rental Affordability Scheme, or NRAS, which funded about 37,000 new homes renting at a 20 per cent discount to the market. The Canadian government is also leveraging its fund to achieve other objectives: projects must outperform existing national codes on energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions by 25 per cent or more and at least one in five dwellings must meet specified accessibility criteria.

On top of all that, Canada’s strategy sets a target of halving chronic homelessness within ten years through a C$2.2 billion program that Siddall said would take a housing-first approach, regarded by many advocates as the most effective long-term way to tackle the problem.

The relevance of the Canadian example was not lost on the Australian audience. Measured by housing prices and the pace of their rises, Toronto and Vancouver are up there with Sydney and Melbourne. Both countries are federations, with split responsibilities across three tiers of government complicating housing policy. Both struggle to find a coherent response to chronic homelessness.

Perhaps the reason that Siddall’s presentation had the Sydney audience buzzing was the extent to which the approach of the Canadian government appeared to reflect their own aspirations for policy in Australia. This goes beyond the language of human rights to encompass the benefits of secure, appropriate and affordable housing for health, education, employment and economic growth. Siddall, who helped develop the strategy and described his role in the Canadian system as equivalent to that of a deputy housing minister, cited research showing that housing has “a higher multiplier effect than personal or corporate tax cuts” with a return of $1.50 for every $1 invested. He described the strategy as “community renewal on a national scale” and said the Trudeau government conceived housing as “shelter, not bricks and mortar.”

The sincerity of Trudeau’s promises will only become clear over time. Australia, too, has had a prime minister who vowed to halve homelessness and then found the problem to be far more intractable than expected. Critics note that Trudeau’s new approach to homelessness won’t be launched until early 2019, about six months before Canada’s next federal election. Another key element of the program, a C$4 billion rent subsidy called the Canada Housing Benefit (which looks like it might be similar to Australia’s Commonwealth Rent Assistance) is not due to start until six months after that election, in April 2020. As Australian housing advocates know only too well, programs are only durable if they have bipartisan support solid enough to withstand changes of government and changing budgetary circumstances.

Still, Evan Siddall’s presentation on Canada’s strategy set the tone for many conversations during the rest of the conference. For the more optimistically inclined, there was a sense that measures announced by treasurer Scott Morrison in this year’s federal budget had also moved Australia closer to a coherent national policy.

The most significant step is the creation of the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation. If it works, the NHFIC will attract new long-term institutional investment into affordable housing by acting as a bridge between community housing providers and superannuation funds. While community organisations can, and do, borrow from banks, each loan must be separately negotiated. Super funds won’t deal one-on-one with individual providers in this way, so the NHFIC and its associated bond aggregator aim to offer them a standardised, rated investment product. “The NHFIC is not a national housing policy,” said Carrie Hamilton from the Housing Action Network, “but it is a very important piece of the puzzle.”

Hamilton was introducing a keynote presentation by Piers Williamson, chief executive of the Housing Finance Corporation. This British forerunner of the NHFIC was set up in 1987, after Margaret Thatcher’s controversial “right-to-buy” program had depleted Britain’s supply of affordable rental dwellings by selling off council houses. It provides long-term loans to Britain’s 170 individual housing associations, which between them own 2.49 million homes and account for 10.5 per cent of all housing.

Williamson, who is advising the Australian government on setting up the NHFIC, described himself as a specialist in risk — “not in taking risks but avoiding them.” He is proud of the fact that no bank or institutional investor has lost money lending to a British housing association over the corporation’s thirty-year history. He also points out that the Housing Finance Corporation helps smooth economic cycles. When commercial banks were falling over in the global financial crisis, its lending grew. Under a government scheme introduced in 2013, the Corporation also guarantees loans to housing associations, reducing the cumulative cost of borrowing for affordable housing, he says, from 3.7 per cent to 2.5 per cent.

On the final day of the conference, when assistant treasurer Michael Sukkar announced that the Commonwealth would offer a similar guarantee on bonds issued by the NHFIC, delegates burst into spontaneous applause. Two other announcements also pleased the audience. The first was that the NHFIC will have an independent board when it begins operations on 1 July 2018. Williamson had earlier told the conference that independence has been crucial to the success of Britain’s housing finance corporation because “politicians always like to dabble and dabbling is not always good.” Sukkar’s third bit of news was that a $1 billion facility set up to finance infrastructure to expedite new housing supply will now be ongoing, rather than terminating after five years.

The NHFIC has the backing of both Labor and the Greens, which means it should survive any change of government, and in his conference speech Sukkar added some small but essential elements that move it closer to being a core piece in the bigger picture of a coherent national housing strategy. But the most important part of the puzzle is still absent — government money.

“Subsidised housing requires a subsidy,” Williamson told the conference. He said that “sitting at the bottom” of Britain’s affordable housing model was £45 billion (A$75 billion) in grant money. “Grants,” he said, “are one of the things missing over here.”

The crucial role of public investment in providing housing for low-income households is well established. Private developers will not build affordable housing because it does not make commercial sense for them to do so. It’s a clear case of market failure.

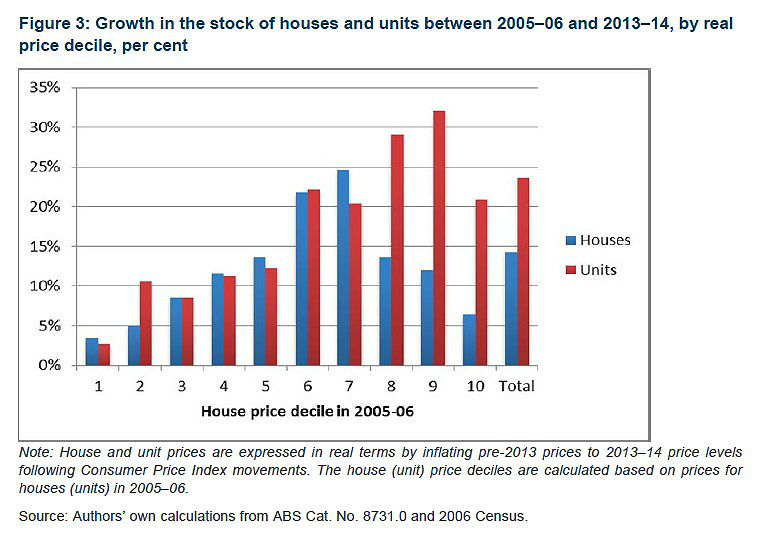

Two charts from reports by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, or AHURI, help illustrate the point. The first, from a report on the responsiveness of Australia’s housing supply, tracks new dwelling supply over a decade. The authors argue that this data shows that the vast majority of new houses and units are “concentrated in the mid-to-high price deciles” and that there is a “paucity of new supply at the bottom end of the housing market.”

In theory, though, an increase in higher-priced supply should still help reduce the cost of housing overall. As buyers or renters of more expensive homes move up the property ladder, they release their former cheaper dwellings onto the market — a process known as filtering. If filtering works effectively (and there are arguments about that), then what matters for affordability is not so much an increase in supply at the bottom of the market as an increase in supply overall. But what is happening to supply is also disputed, as seen in a current public debate between leading Australian housing researchers.

Ben Phillips and Cukkoo Joseph at ANU’s Centre for Social Research and Methods recently concluded that Australia had an oversupply of new dwellings between 2001 and 2017. If this is correct, then other factors must be stopping filtering from increasing affordability. If new properties are bought as second homes or by overseas investors, for example, then there is no previous property to filter down.

But the Grattan Institute challenges the ANU analysis of oversupply. “Phillips and Joseph ignore how rising prices and worsening affordability pushed people into larger households than they would have chosen,” wrote John Daley and Brendan Coates in response to the report. “And so their estimates underplay the number of dwellings needed to accommodate Australia’s growing population.” Daley and Coates give the example of young people staying longer in the family home than in the past and conclude that this is less likely to be driven by “a social wave of filial affection” than by the fact that “there is less housing to go round.”

Even if the Grattan Institute is right that “a sustained increase in supply over several years” would materially lower prices, it will be a slow process, because high rates of new construction only increase the stock of existing dwellings very gradually. This is why many delegates at the Sydney conference focused less on market settings and more on public investment in social and affordable housing.

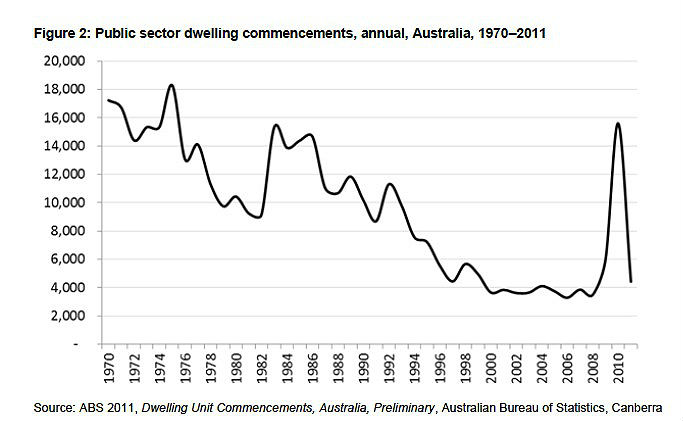

Which brings us to the second chart, from an AHURI report on public housing that shows how government investment in the sector has tracked steadily downwards over a thirty-year period, with one brief, spectacular exception. The blip in the chart that resembles the sudden resuscitation of a stalled heartbeat is the dramatic effect of Kevin Rudd’s second stimulus package during the global financial crisis. In February 2009, Labor pumped $42 billion into the economy, including $6.6 billion to build 20,000 new units of social housing dwellings and 802 defence homes. At the time, surprised housing advocates called it a “quantum leap” for the sector. As soon as the stimulus ran out, though, construction of social housing fell off a cliff and the heartbeat of Australia’s social housing sector returned to its dangerously low levels.

On the same day as Justin Trudeau was launching Canada’s national housing strategy, the British government released its autumn budget, which included “£15.3 billion of new financial support for housing over the next five years, bringing total support for housing to at least £44 billion over this period.” Oona Goldsworthy, CEO of Bristol housing provider United Communities, who was at the Sydney conference, told me that “a lot of government effort” is going into housing in Britain, with prime minister Theresa May giving it equal priority, or greater, to health, education and growth.

Despite Michael Sukkar’s announcements, housing doesn’t seem to be getting the same level of attention here. Nor is there evidence of the cohesive approach that unites all levels of government as in Canada. This became obvious at a conference session that brought together senior state, territory and federal public servants. The focus was on housing policy innovation around the nation but the session ended in a degree of acrimony.

The final speaker was Paul McBride, manager of welfare and housing reform in the Commonwealth Department of Social Services. He was endeavouring to explain why the federal government wants to replace its existing deal with the states and territories — the National Affordable Housing Agreement, or NAHA — with a new National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, or NHHA. This was another 2017 budget initiative but it has stalled, not least because of resistance from state governments.

The Commonwealth says NAHA has failed because only one of the four performance benchmarks set up under the agreement has been met. Despite $9 billion in funding since 2009, “growth in the size of the social housing stock has stagnated and numbers on waiting lists have increased.” In return for future funding under the replacement NHHA, the Commonwealth wants the states and territories to put in place credible housing and homelessness strategies and provide data for transparent and consistent reporting. As an incentive, it is offering to index $115 million in annual funding for homelessness services provided under the current agreement and to make that funding permanent.

When McBride described this as “a significant concession from the Commonwealth,” Caryn Kakas, executive director of Housing NSW, shook her head in disbelief. She accused Canberra of holding the states hostage over housing funding. “If the Commonwealth is serious, it should be putting forward a national housing strategy, not just stitching together state programs,” she retorted. She pointed out that the Commonwealth can pull levers like tax reform that are beyond the reach of the states and territories. McBride’s response was interrupted by interjections from the floor. “There’s no strategy, absolutely none,” yelled one delegate. “Spend more money!” called out another.

McBride had earlier noted that treasurer Scott Morrison “wants a pathway to home ownership” and that all subsidies and state programs should point in that direction. And this is perhaps where the difference in views really resides. For most of those at the conference, the core issue is not assisting first homebuyers to take their initial step up the property ladder, but helping low-income households to put a secure roof over their heads.

Sydney University’s Nicole Gurran told the final conference session that Australia lacks a properly funded social housing system, which would require government and institutional investment to increase supply at the bottom of the market. “If we want stable supply, then we have to be serious about building, irrespective of the fluctuations of the real estate market,” she said. “And we have to make sure that we are delivering what we really need, and that’s affordable, new rental housing.”

Gurran noted that forgoing billions of dollars in revenue through negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount failed to deliver this outcome. Labor has promised to reform negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount if it wins the next election. Even if it only saved half of the $11.7 billion calculated to be lost on these concessions to property investors annually, that would still bring in enough funding to revive the heartbeat of Australia’s social and affordable housing sector, not just in a one-off stimulus package, but year on year. Wherever the money ultimately comes from, if we want a national housing strategy, public investment is still a missing piece of the puzzle. ●