Who would we say is the greatest American composer of the twentieth century? I don’t mean songwriters, but concert-hall composers.

Aaron Copland would be a popular choice. It was Copland, after all, who in the late 1930s and 40s invented what some still dismiss as “cowboy music”: ballet scores such as Billy the Kid, Appalachian Spring and Rodeo, full of wide open spaces, revivalist hymns and hoe-downs.

His modernist contemporary, Elliott Carter, composing from around the time of the Wall Street crash until after the global financial crisis (well into his 104th year), might be another contender. What about Philip Glass? He’s one of the few living composers whose music and face are known to a wide public. And let me mention Roy Harris, forgotten but for his terse, single-movement Symphony No. 3 of 1939: in many people’s view (mine included) there is still no greater symphony by an American.

Shall we broaden the discussion to pop? Can we go past its éminence grise of five decades, Quincy Jones? Since we’re talking about the United States, we can hardly rule out composers for TV and film. Is there a better-known theme in either sphere than the fiercely syncopated Mission Impossible theme of Lalo Schifrin?

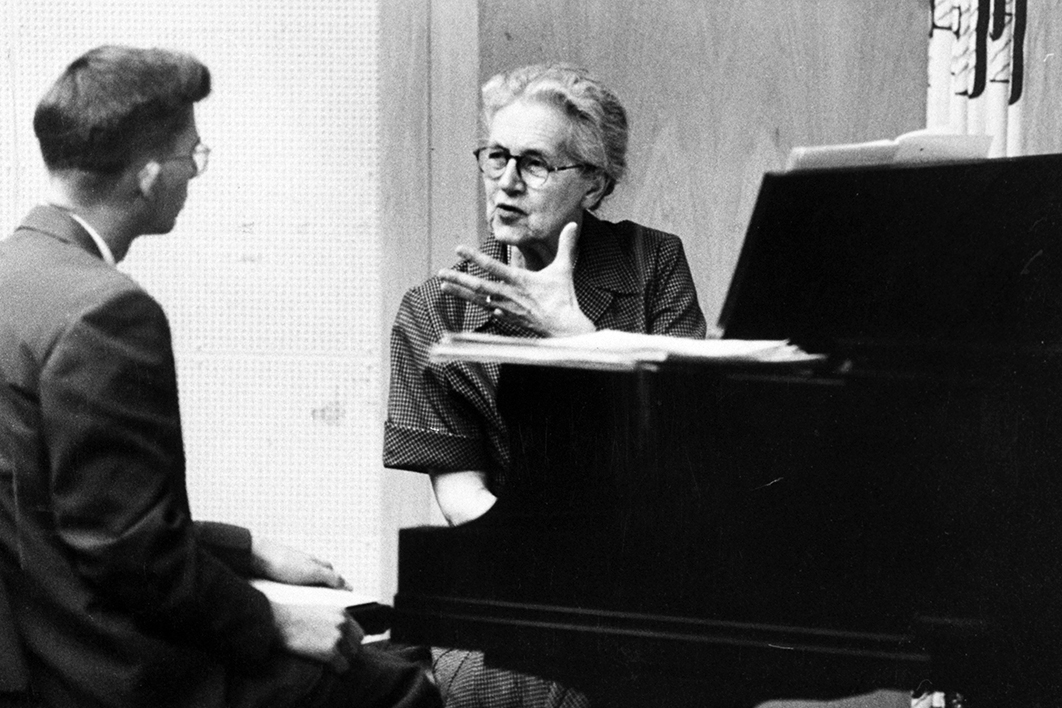

This is, of course, a pointless game, but my reason for playing it is to draw attention to the fact that Copland, Carter, Glass, Harris, Jones and Schifrin shared a teacher. And we can add to the pupil list Jean Françaix, Lennox Berkeley and Peggy Glanville-Hicks, Burt Bacharach and Michel Legrand, tango composer and bandoneonist Ástor Piazzolla and jazz trumpeter Donald Byrd. From the 1920s till the 1960s, composers of all stripes — particularly American composers — beat a path to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger.

Boulanger, born in 1887, and her younger sister, Lili, were precocious musical talents. Their elderly father was a singing teacher, their mother a Russian princess who had been his student. Both girls studied composition with Gabriel Fauré at the Paris Conservatoire, but Lili’s gifts were greater in this regard.

After Lili’s death in 1918 at the age of twenty-four, Nadia stopped composing. This seems to have been almost out of respect for her sister: Lili had been the composer; now Nadia would teach and perform. She became a trailblazer in both areas, though she held some socially conservative views, especially concerning the place of women in music. In spite of her late sister’s talents, and despite the presence in her classes not only of Glanville-Hicks but also, later, of Priaulx Rainier and Thea Musgrave, Boulanger believed a woman’s first responsibility was to be a wife and mother. Not that she became either.

In the “Boulangerie,” as her class was nicknamed, she taught harmony and counterpoint with reference to existing musical works rather than simply through exercises; students sight-sang their way through Bach’s cantatas and studied music from before Bach’s time through to their own. Stravinsky’s music, which from the 1920s to the 1950s itself showed the influence of Bach, was a prime exemplar of her influence. As a conductor, Boulanger presided over the first performance of Dumbarton Oaks, sometimes referred to as Stravinsky’s “Brandenburg Concerto,” and the composer became a personal friend, sending his son Soulima to study with her. There recently appeared a slightly disappointing volume of correspondence between Boulanger and the Stravinsky family, less concerned with music than with birthday greetings and travel arrangements. Mind you, the fact that it filled a book underlines their closeness.

Boulanger, whose reputation as a pedagogue preceded her, became the first woman to conduct the New York Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the London Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony Orchestra. This was not an achievement that much impressed Boulanger herself.

“I’ve been a woman for a little over fifty years,” she said, “and have recovered from my initial astonishment. As for conducting an orchestra, I do not believe this is a job where sex plays much of a role.”

What does still seem astonishing about her conducting was the music she chose to present. It was generally works that would have been unfamiliar to her listeners: new music, much of it being heard for the first time (some of it by her former students), and old music that in many cases had been lying dormant for centuries.

A recent collection, on the Eloquence label, of Boulanger’s American Decca recordings from the 1950s concentrates on music of Renaissance and baroque composers such as Josquin, Janequin and Lassus, Monteverdi, Charpentier and Rameau, together with Brahms’s second book of Liebeslieder waltzes. Some of the recordings now sound their age, the performance of baroque instrumental music having come a fair way over the last seventy years, but choral madrigals by Monteverdi and the French Renaissance composers are rather sprightly.

Boulanger had recorded Monteverdi between the wars, using a piano. Here she uses a harpsichord, which she plays herself, but there is little else in these recordings by way of “historically informed” style. Instinct plays a far greater part. By comparison with the recordings of Raymond Leppard, say, who recorded Monteverdi’s madrigals in the 1960s and whose harpsichord playing is characterised by a lot of unnecessary flourishes, Boulanger’s recordings from the decade before are direct and unfussy, and all the better for it.

Working almost to the end of her life, Boulanger died in 1979, her composition students having since begat composition students of their own, their students begetting yet more students. The Boulanger dynasty is established. But her baroque recordings reveal a different lineage, a scholarly and performative tradition that points the way to modern performances but also looks back, and not only to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Late-nineteenth-century Paris is also here. This was where so much early music was rediscovered.

Many of the musical archaeologists were themselves composers, people such as Vincent d’Indy and Camille Saint-Saëns; Boulanger’s own teacher, Fauré, offered encouragement and introduced this music to the Conservatoire, where from 1905 he was director.

In her recordings, we sense the astonishment and excitement the young Nadia must have felt being around such discoveries. She makes us feel this, too. •