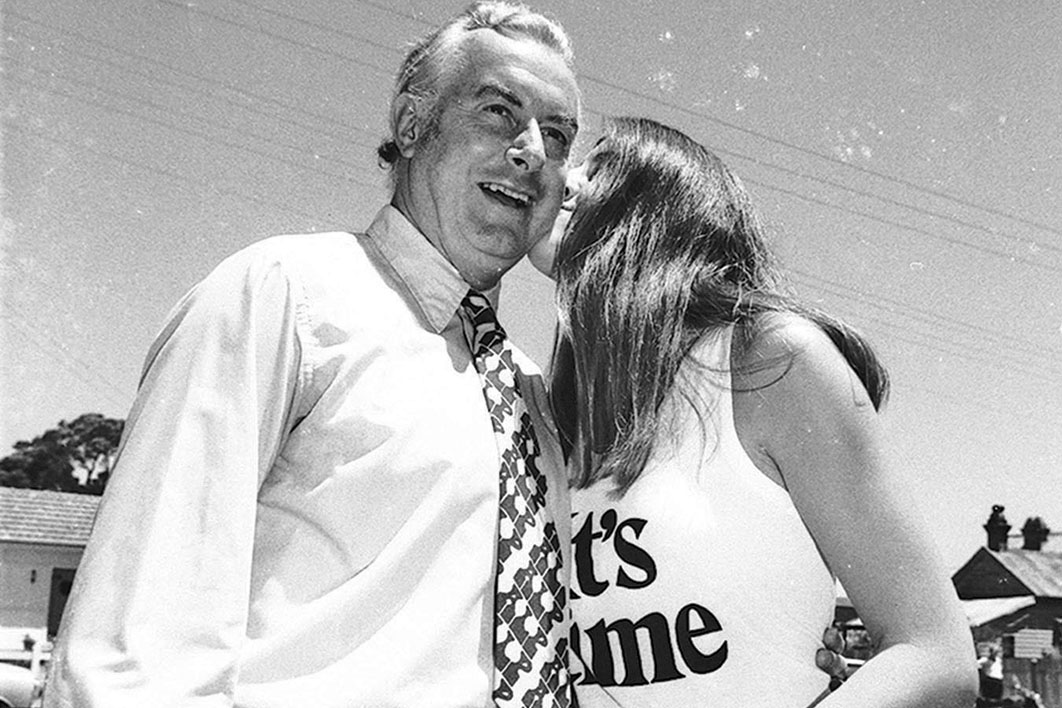

As campaign slogans go, it was as near to perfect as they come. Informal, strong, urgent and memorable. Two words: a perfect fit to the political climate, a perfect encapsulation of a political strategy and a perfectly simple tag to sustain an entire marketing campaign. Short enough for a badge or T-shirt, but with enough meaning to support the policy speech. And good enough to sing.

The iconic slogan that took Labor to office forty years ago originated with a report handed by the party’s advertising agency to its NSW branch in December 1971. The report was encased in a plain black cover bearing the words, “It’s Time.”

Before 1972, political parties didn’t really have national campaign slogans. Each state branch was free to concoct its own way of rallying the voters, and local candidates might have their own catch-cry as well. Labor’s federal secretary, Mick Young, who had ridiculed how Labor had had “more slogans than candidates” in the 1969 election, was determined that things would be different in 1972. There would be one single message that would animate the campaign in every state and on every piece of advertising. And by campaign, he didn’t mean a three-week burst prior to election day; he meant a sustained, year-long effort of persuasion and promotion.

So when the NSW state secretary, Peter Westerway, received the agency report with its short, sharp slogan, he passed it on to Young. Young liked it but was worried it might hold some unforseen negative connotation, so he commissioned market research to test the slogan with 1100 voters in four capital cities. It passed with flying colours. “It generates a feeling of urgency that it’s time to change to a Labor Government,” the researchers reported.

Its genius lies in its declaratory strength combined with an infinite flexibility. It’s time! But for what? As the ad agent who hit on the phrase, Paul Jones of Hansen Rubensohn–McCann Erickson, put it, “You say, ‘it’s time,’ and they’ll fill in what it’s time for. It’s time to bring the diggers home [from Vietnam]. It’s time to stop strikes, fix education, whatever is important to the individual.”

This set the tone for the launch of the slogan in early 1972 on a confetti of bumper stickers, badges, T-shirts and skivvies. Then came the “It’s Time” anthem, which formed the basis of Young’s national TV advertising campaign, in August 1972 – fully four months from election day. Sung by a chorus of showbiz celebrities, the anthem’s meaning is entirely open-ended. It’s time for freedom, for moving, for loving, for caring. It’s time for old folks and time for children. Explicit meanings – time to change government, time to vote Labor – could be left unsaid; the anthem doesn’t even mention Labor or Gough Whitlam. Young’s strategy, simply put, was to create a national mood for change. “It’s Time” conveyed hope, anticipation and excitement without the burden of specific policy commitments. Moreover, as Jones had said, “there’s nothing to disagree with.” “It’s Time” simply could not be attacked (and the Liberals’ effort to do so, with the dismal “Not Yet,” just proves the point).

At the time, Young believed it was the best slogan since federation. Forty years on, it’s impossible to think of anything to knock it off that perch. It works on the emotions, unlike Hawke’s rationalist “Reconciliation, Recovery, Reconstruction” (1983). It suggests a more effective strategy than Hewson’s “Fightback!” (1993). Try fitting “Don’t Change Horses in Midstream” (Labor, 1987) on a badge. And unlike the vacuous gerunds (Gillard’s disastrous “Moving Forward” in 2010) or the to-stand-in-front-of nouns (Howard’s bizarre 1987 “Incentivation,” Keating’s 1996 “Leadership”), “It’s Time” forms a grammatically correct sentence. The only slogan that comes close was Fraser’s “Turn on the Lights” (1975); but “It’s Time” is simpler, non-metaphorical, more direct, more upbeat.

Labor’s 1972 campaign was distinctive in more than its slogan. It was the first recognisably modern, professional, national election campaign. It was a transformative event in Australian electoral politics, the birth of modern election campaigning. Young acknowledged, in a speech in the 1980s, that the campaign had changed the face of election campaigning in Australia. But even he might be surprised by the extent to which contemporary politics still swings along to the rhythms of that remarkable campaign.

To understand its significance one must track back to Labor’s murky organisational politics of the mid and late 1960s, which nearly prevented Young’s election as Labor’s federal secretary. It was just three years before Labor was to win office, but the party did not remotely look capable of governing itself, let alone the country. Whitlam’s heroic contribution to the transformation – rebuilding the platform, reforming the party through intervention in the recalcitrant Victorian branch, renewing links with voters – is well-known through accounts such as Graham Freudenberg’s A Certain Grandeur and Ross McMullin’s official party history The Light on the Hill.

Less well-known is the turmoil in the back room, where the party’s head office also needed a complete refit to prove itself capable of managing a successful election campaign.

Young’s predecessor had been the “cockney sparrow,” London-born Cyril Wyndham. Labor’s first full-time national secretary, Wyndham had set up the party’s headquarters in the national capital – though that is perhaps too grand a term for the dingy rented office in Civic, the loyal staff of two, and the shoestring budget. An articulate and fluent party spokesman, Wyndham was a reformer allied to Whitlam. But he lived to regret his move to Canberra. His plan to democratise the party’s decision-making had, almost predictably, been shelved by the factions and the state branches.

In particular, Wyndham’s erstwhile mentor, the Western Australian secretary Joe Chamberlain, had turned against him: the archetypal left traditionalist and party bureaucrat, Chamberlain stood to lose from reform. By 1969 the knives were out: in an appalling set-up, Labor’s federal executive conducted an audit of party finances that found a number of administrative errors by Wyndham. Frustrated, Wyndham resigned without explanation in March 1969. (After a long retirement in Newcastle, Wyndham died in July this year; his death passed without comment from the Labor’s head office.)

The head office vacancy came at a bad time, with the party facing a national conference in August and a federal election by the end of the year. Moreover, Chamberlain saw it as an opportunity to extend his already prolonged and influential career in the party. Already sixty-nine years old, he was another Londoner who migrated to Perth after the first world war to find work. He had climbed the ladder of the labour movement to become Labor’s WA secretary in 1949 and went on to serve as federal president in the late 1950s and federal secretary before Wyndham.

So when federal executive met to elect Wyndham’s replacement, Chamberlain put his hand up. Mick Young, South Australia’s party secretary, had only been a member of the executive for twelve months and regarded the idea of electing Chamberlain “at his age, and with his views” as an “absolute political disaster.” More in the spirit of protest, Young decided over dinner to contest the ballot himself. The contrast was sharp – a generational battle, a factional battle, a hard-line traditionalist against a pragmatic moderniser, a Whitlam enemy against a Whitlam supporter, a party bureaucrat steeped in rules and procedures against a new breed campaign professional. Chamberlain didn’t think the Labor Party should necessarily try to win elections and did not mind it when they lost; Young had already helped Labor topple one long-term Liberal regime – Playford’s in South Australia – and was determined that Labor should govern nationally.

On this occasion, the veteran insider had miscalculated. When the secret ballot was held, one of the Tasmanian delegates unexpectedly opposed Chamberlain. The vote tied at seven each. A second ballot was held. Still seven each. But Chamberlain knew he was beaten and withdrew; Young was elected unopposed. The meeting broke up and delegates drifted off, leaving Young to lock up. He found himself late at night, standing on the footpath of Ainslie Avenue, wondering what he had got himself into.

Better-known as the burly shearer, the knockabout bloke with a “shock of black hair and a face that was a map of Ireland,” in journalist Alan Reid’s description, Young was a shrewd reader of character and, just as importantly, of opinion polls. In two state elections in South Australia, he had worked in the party office that supported Don Dunstan by using – for the first time in Australia – market research and television advertising. He took the same approach in preparing for Whitlam’s 1972 campaign.

In mid 1971, according to future Labor minister Neal Blewett, a “group of wealthy Whitlam supporters” donated $5000 for a national survey on Whitlam’s image. Young used the results by giving Whitlam more exposure to female voters through talkback radio and daytime TV, and implored him to speak in shorter, simpler sentences – straightforward tactical ideas, but innovative for the time, and clever. Young organised for a mini-campaign of policy announcements by Whitlam and his shadow ministers during November and December, which generated free news coverage – not all of it positive, but successful enough and, as Young said, “completely right in concept.” This was all a precursor to the “It’s Time” campaign itself, driven and tested by market research, centrally produced and nationally disseminated, its message integrated across all media outlets, making an entirely emotional pitch after an era in which advertising had been largely policy-based appeals to voters’ hip-pockets.

But the transformative impact of Young’s campaign relied on more than clever use of an advertising agency. After the failure of Wyndham’s efforts to reduce the power of the state officials, Young’s real success lay in the organisational arrangements he put in place to manage this campaign. “To win federal government,” he recalled in a speech in 1986, “we had to run a properly coordinated national campaign.” The biggest hurdle was the “jealousy and suspicion that existed between the national office and the state branches,” which had led each branch to run its own campaigns.

What was needed was a framework for coordinating and centralising campaign authority – and Mick Young was just the man. In January 1972 he was appointed to a newly created post: Labor’s national campaign director. Previously, each state secretary had been campaign director within the boundaries of that state; now there was one, at the centre. Labor also set up a national campaign committee – again, a first – through which Young developed and implemented the campaign strategy, co-opted the state branches, coordinated the activities of Whitlam and the shadow ministry, and directed the ad agency and market researchers. The national head office, shut down after Wyndham’s ouster, was reopened and strengthened with the hiring of professional journalists and PR consultants.

In the event, campaigns in New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria were almost entirely directed from the centre. In Western Australia, Joe Chamberlain still held the reins of power but was ill as well as pessimistic and rarely attended the national campaign meetings; as Blewett notes, the national committee directed sufficient funds across the Nullarbor to ensure broad national consistency. Only Queensland insisted on running its own campaign, with its own signage and messaging. Marginal seats remained the prerogative of the states, but these campaigns too were closely supervised from the centre, with campaign visits by Whitlam and the shadow ministry carefully focused on the key winnable electorates.

Young was also on top of the campaign budget in a new way. Labor had never spent money like it was spending on this campaign. He set an aggressive fundraising target of $250,000 – five times the national budget of the previous campaign, in 1969 – and, next to Whitlam, was at the forefront of fundraising appeals to business. He also exercised tight control over spending, ordering the ad agency to spend nothing without his explicit authorisation and thus ensuring the party only spent what it raised.

Young transformed the way campaigns were managed. He integrated market research and television advertising better than anyone had done previously, practising on a national stage the skills he had acquired at the state level. He built a national campaign strategy – creating, over months, a national mood for change, and projecting a uniform message into living rooms across the nation. The technology for a national campaign had been available for some years; Young was the first to exploit it by overcoming the state parochialism that had stood in its way. Never had an ALP campaign so fully justified its adjective Australian. Young also put campaign resources into the seats where they were needed – based on national electoral needs rather than parochial state perceptions. He developed Labor’s campaign resources – its campaign skills and know-how as well as its financial resources – and dragged fundraising into the modern era.

The Liberal Party certainly recognised Young’s achievement. The “It’s Time” slogan, according to deputy leader Phillip Lynch, was “the brightest and most bouncing baby ever conceived and brought forth within the marriage of advertising and politics.” Shattered by their first election defeat in a quarter of a century, the Liberals eased out their federal director, Bede Hartcher, and allowed an energetic McKinsey management consultant, Timothy Pascoe, to reorganise head office before handing it over to an experienced journalist and PR specialist, Tony Eggleton, who became the third federal director in the space of a year. Recognising that they, too, had become fragmented by state boundaries, the Liberals openly copied Labor’s ideas and appointed Eggleton as national campaign director for the 1975 campaign. State officials were brought into line, television advertising was put on a national footing with a single agency and a single campaign message – and the professional campaign model was under way.

The enduring influence of the 1972 campaign is marked in other ways. Newspapers competed by reporting rival opinion polls. A new genre of post-election books by journalists emerged, pioneered by Laurie Oakes and David Solomon’s The Making of an Australian Prime Minister. Academics, led by Sydney University politics professor Henry Mayer, who edited Labor to Power, began a stream of campaign documentation and analysis that has continued almost unbroken to this day. (Mayer’s collection includes two gems: an account of Young’s campaign by Neal Blewett, who was then a young academic from Flinders University, and a quirky perspective on advertising written, under a pseudonym, by Paul Jones.)

The most remarkable indication of 1972’s transformative impact, however, comes from looking at election outcomes. Since the Liberal Party was formed in the mid-1940s, it has contested twenty-six elections with Labor. Nine of the first ten were won by the Liberals in coalition: after Ben Chifley’s victory for Labor in the early days of peace in 1946, Robert Menzies won seven on the trot, Harold Holt won a landslide in 1966, and John Gorton got home in 1969. For more than two decades, Labor’s grand aggregate of successful electoral campaigns stood at zero. One-sidedness seemed to be a chronic feature of the Australian electoral landscape.

All that changed in 1972. Labor’s win was a breakthrough in itself, but it also represented the end of that one-sided pattern. Including 1972, Labor won seven of the next ten elections: Whitlam two, Hawke four and Keating one, against Fraser’s three. Having mastered the art of winning from opposition in 1972, Labor mastered the art of winning from government in the 1980s. One-sidedness was replaced by an almost exact parity between the two major parties. Indeed, on the fortieth anniversary of “It’s Time,” it is remarkable to note that since 1972 the two parties have governed for nearly the same amount of time. Labor has been in office for twenty-one years and one month, and the Coalition for eighteen years and eleven months. In percentage terms it comes out at 52.7 per cent for Labor and 47.2 per cent for the Coalition – as finely balanced, almost, as a Newspoll. The hung parliament resulting from the 2010 election, of course, only underlines the delicate balance.

Mick Young died in 1996 of leukaemia. For all that he stands as Australia’s first campaign professional, one suspects he would be uneasy about campaigning today. He always emphasised that market research was no substitute for policy. He would recognise the strategic, technical and financial imperatives of the contemporary party contest between his latest successor as national secretary, George Wright, and his Liberal counterpart, federal director Brian Loughnane. But as they prepare for the 2013 clash, he might remind them, as he said in 1986, that the greatest lesson of the It’s Time campaign was that “something of substance has to be there before it can be sold successfully to the public.” •