Fairfax Media is near the endgame of a largely reactive response to the challenges of digital media, in which the dominant characteristics have been the dissolution of its power and the contraction of what was once a prosperous environment. It seems very likely that the company will soon be owned by foreign private investors with a focus on its real estate advertising revenues.

Like many newspaper publishers, Fairfax responded to the emergence of digital media with unchanged assumptions about its markets. Content had not really been priced in most newspapers; if it was, the price was secondary to reaching the biggest possible audience for advertising. Fairfax and many others made content free on the web, effectively commoditising content that is expensive to produce. The company aimed to add big web audiences to sustain advertising income in a digital world. There has been no strategy for building revenue through content.

Once Google had acquired AdSense and Facebook figured out advertising, the game was up for newspaper advertising. Aggregators have enormous audiences and very, very low costs. Prices collapsed to the point that today about 80 per cent of advertising dollars end up with Google and Facebook. On some indicators, notably the local Standard Media Index, newspaper advertising, already much diminished, has fallen off a cliff in recent months.

Having tossed overboard anything that could be unbolted or cut loose, Fairfax has begun cutting a swathe through the remnant core of its mastheads. Its hope is Domain, which is partly a digital real estate listings business and partly a branded print advertising segment. On the face of it, one or both of the potential owners of Fairfax see it as a base for growth in wider real estate and property services, and perhaps even property transactions (though the latter might be tricky, given the interests of Domain’s partner real estate agents).

Before the bidders showed their hands, Fairfax had planned to split Domain from the mastheads into a structure that would allow it to offer a separate equity interest to shareholders. This “float” of part of Domain is due later this year. Gutted of once-fat incomes, the masthead businesses would presumably lose any connection even with the property advertising. In that event, the news business would appear to be doomed. Which means, to the extent that it is valuable to them, new owners appear to be the only hope for the Fairfax news media.

How might they change course?

The most likely path is suggested in the fact that Domain’s management wants to keep the news mastheads together with the property advertising. This might simply be an admission of the interdependency of Domain’s print and online outlets, or it might reflect a broader strategy. Either way, building Domain profits will be the focus.

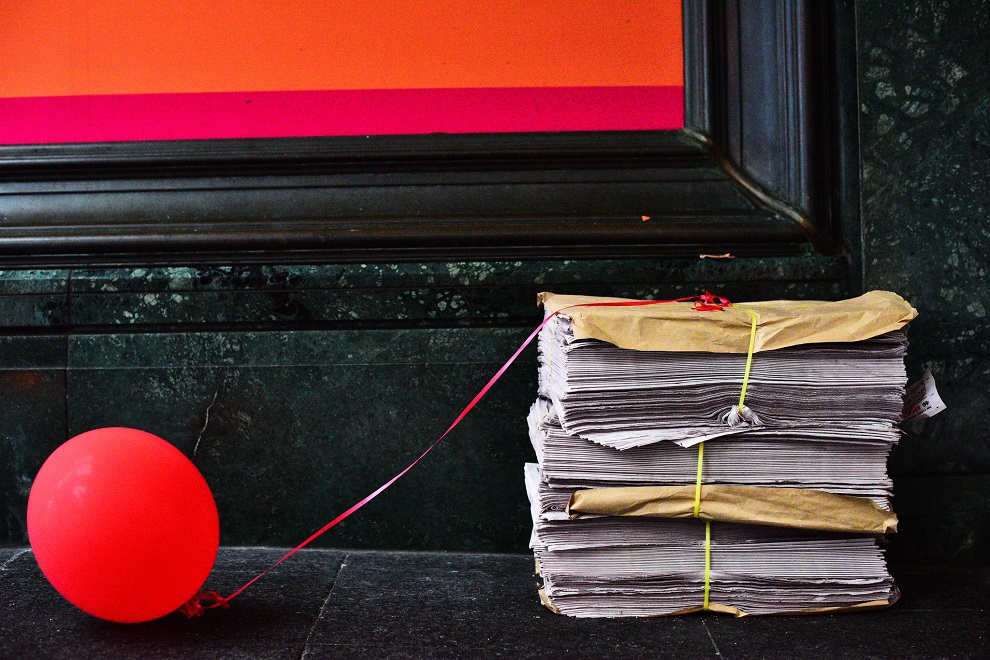

Another course that has been evident for some time, but has only recently become more common, is to make Fairfax explicitly a content business. Netflix, HBO, Amazon and many others are doing very well with paid video content. Big-name news media such as the Financial Times, the New York Times and the Washington Post – and many smaller media businesses around the world – have made viable business out of producing content that people value. The greatest challenges for these publishers have been in shrinking what were huge print manufacturing and shipping operations; Fairfax has largely done that already.

Putting aside the intent and appetite of investors, one of the serious commercial challenges for incumbent news media seeking to make it across the digital divide is the power switch. Consumers today don’t have to accept the product of a dominant channel with a broad offering of content, which was how the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald acquired their lustre. People, like Jeff Bezos, who succeed in winning over digital customers are obsessed with customer value. This is not a concept a traditional editor or publisher would recognise. It is the driver of Amazon Prime, for example, which charges consumers a subscription for what is – or was – a shopping channel. It is the digital media driver.

News publishers exploring the value question have encountered challenging facts. Readers don’t much notice who writes what they read. Of course there are prominent names, but the industry’s obsession with celebrity does not correspond with value. Readers want to be informed. (So the tendency to reduce cost by loading up on opinionated columnists is somewhat counterproductive, if not simply destructive.)

When it comes to winning audiences willing to pay for news, digital publishers need to go hard in the Bezos direction and deliver what those people want – reliable news and information that’s of value to them. In effect, digital consumers control the channel, which is a tool that gives them choice.

Whether or not Fairfax’s news media is valued solely as a prop for Domain, at least its potential new owners have valued it. The next commercial imperative is to make news valuable for its own sake, a course that offers Fairfax’s news media a real future. •